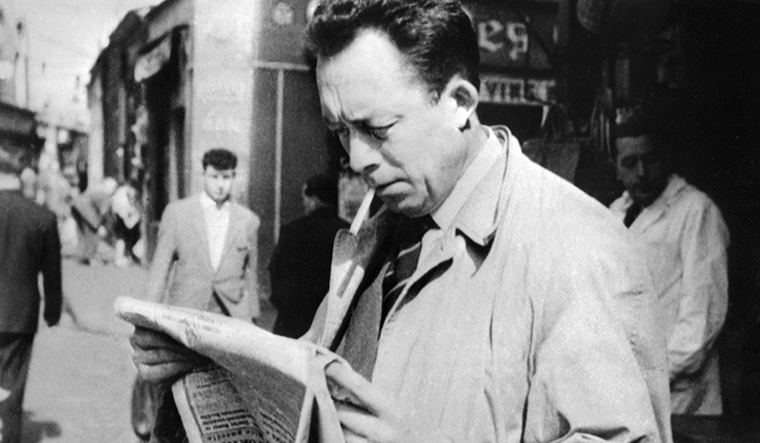

Much has been written about French-Algerian philosopher and writer Albert Camus’s novel La Peste (The Plague). Multiple media outlets have looked at the relevance of La Peste in the time of Covid-19. The BBC reports that sales of the book have gone up in France, Italy and Britain this year, and that it is currently in reprint.

La Peste came out in 1947. Having read the book once again this week, I am not on the lookout for philosophical, metaphysical, or even literary gains from it. My focus is simply on key insights that can make us smarter in these times, as well as later in life.

The novel is set in the plague-hit town of Oran in Algeria, and records the response of the town, including the medical community and volunteers. The story is narrated by Dr Bernard Rieux, a doctor who is treating plague victims. Though the central theme is the epidemic, the novel tries to widen its scope to include ‘pestilences’ in general, both natural and manmade, and the resultant human suffering and resistance.

Here are three key insights from La Peste.

The larger historical landscape

Through Rieux’s narrative, Camus, in the initial chapters, positions the Oran epidemic in a larger context by giving details of previous plagues in history. This includes historical accounts of the Justinian Plague of Constantinople, the Black Death of Marseilles, the Great Plague of London, the Great Plague of Milan and the Plague of Athens. Also, in the final chapter, the author clearly mentions the possibility of such epidemics recurring in future. Thus, Camus offers a model of understanding the catastrophe as an event in history, rather than a singular challenge outside of time. This is important because, to us, the current pandemic appears as an all-encompassing topic overriding all other events. We are fully consumed by thoughts of it while Camus suggests that this need not be the case. Plagues are a part of human existence. Disaster preparedness would be one of our best responses.

Optimal use of time

The author offers a defence against the repetitive and unpredictable calamities which threaten our existence: a proper use of the time available to us. To illustrate this, he uses the examples of Rieux’s silent and relatively unexpressed love for his mother and his relationship with his friend, Jean Tarrou, who had died “without their friendship’s having had time to enter fully into the life of either”.

Camus opines that love is perhaps the most precious and fulfilling entity that one can attain in an unpredictable world. For people with greater and more abstract aspirations, time is a limiting factor. Our lives are inherently unpredictable, with the possibilities of recurring plagues and calamities. Hence, finding time for love and happiness is crucial.

The significance of a chronicle

In the book, many volunteers fighting the plague succumb to it, including Jean Tarrou, Magistrate Othon and Father Paneloux. When the epidemic finally comes to an end, the dead are forgotten in the egoistic but necessary celebrations of the living. Rieux decides to compile a chronicle amid the celebrations to “bear witness to those plague-stricken people, so that some memorial of the injustice and outrage done them might endure”. Also, he wants to state “quite simply, what we learn in a time of pestilence”.

The medical information website Medscape is making a list of all the frontline health care workers who succumbed to Covid-19. It is an effort to remember, and remember we must.

The book offers many more important insights. In conclusion, one is compelled to add a small conversation between journalist Rambert and Rieux.

“Who taught you all this, doctor?”

The reply came promptly.

“Suffering”.

The author is a consultant psychiatrist.