French philosopher Gaston Bachelard is hardly a familiar name for people more accustomed to Aristotle, Socrates or Nietzsche. But he wrote some of the most lyrical passages on what constitutes 'home' in The Poetics of Space (1958)—a book for architects who are willing to create a house that “protects the daydreamer” and reflects the soul of the inhabitant.

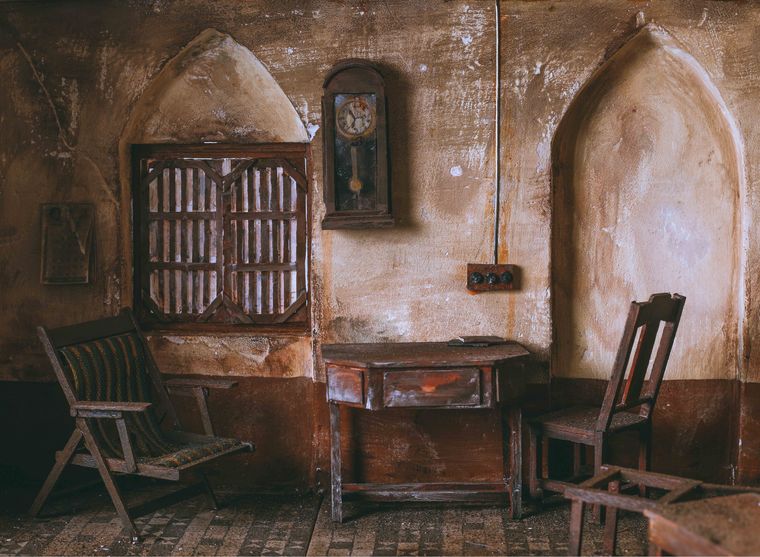

While architects are not exactly reading Bachelard, you can trust an artist to construct emotional domestic spaces. Which is what Goa-based Sahil Naik did in his sculptural artwork, '38 Sinkings', in an attempt to learn how people reconcile with not just a loss of home and land, but a way of life. Commissioned by the Serendipity Arts Festival last year as part of the Urban Reimagined 2.0 exhibition, '38 Sinkings' has recreated homes from the Goan village of Curdi that was drowned forever by the waters of a dam in 1978, displacing some 3,000 families. Every summer, Curdi reappears for about a month, and villagers return for a festival at the Someshwar temple ruins or the feast of the Holy Cross Chapel. “This becomes an occasion to not only come together but also recollect.... Here is where I began to create these sculptures—between the lived and the imagined—from fragments of these stories,” says Naik. '38 Sinkings' is titled after the number of times the village has submerged. “It is used as a measure of time—a period of waiting and longing for the people of Curdi,” says Naik. He has visited the elusive village for the last five summers, and says we must consistently remind ourselves that the price for development is paid most heavily by those who cannot afford it. “We must continue to resist and build support structures all the more in today’s political climate, where politics seeks to invalidate people's claim to home, life, belief and belonging,” he says. “38 Sinkings, ultimately, is a reminder of a failed ambitious political dream, one that continues to affect many, even decades later.”

As a nation scorches the streets to secure home and hearth as rightful citizens, it helps to look at how artists are responding in newer ways to this anxious feeling of displacement and un-belonging. For Delhi-based lensman Sharbendu De, showcasing the endangered Lisu tribe from Arunachal Pradesh in a photojournalistic or “colonial-anthropological” style would be a disservice to their way of life and philosophy. In 1983, the Tibeto-Burman tribe became “encroachers” in their own land when the government subsumed their area of residence within the Namdapha National Park in Arunachal Pradesh. They now live deep in the forest from where there are hardly any roads to reach the nearest town, which is at least 150km away. Still, the community is beautifully self-sustained. “They are so disciplined. There is no crime, only care, love and gentleness. But how do I show their magical qualities of grace and gentleness?” asks De, who has known the community for seven years. So in 'Imagined Homeland', made with grants from the India Foundation for the Arts and scholarship from Lucie Foundation, he imbues his frames with elements of magical realism, evoking a bluish, neon dreamscape where “ducks, horses, television, winter fog, forest, darkness and the elusive light” create an aura of eternal waiting, a belief in a higher, redemptive force.

Bachelard wrote “when your home trembles in its beams and turns on its keel, you think you are a sailor rocked by the breeze”. One can feel the hotfooted rush of the sentence in 'Boy With a Suitcase', performed at the Serendipity Arts Festival last month. A Ranga Shankara and Schauburg production, it is written by British writer Mike Kenny, directed by German thespian Andrea Gronemeyer and held together by a cast of multiple nationalities. The play is a celebration of how societies evolve and become richer with cross-pollination of cultures. A 12-year-old boy is forced to flee as his hometown falls under siege by marauding forces. His parents manage to put him on a boat by selling all their belongings. He downplays his precarious circumstances by thinking of himself as a sailor like Sinbad who dodges every hurdle in his voyage to reach London, where his sister is struggling to make ends meet.

In 'Please Feel at Home', another play shown at Serendipity, an older woman waits for a tenant to occupy what used to be her son's room. As she prepares the room for the new occupant, she becomes paranoid about the stranger's identity. What if he is a meat-eating Muslim? A Bangladeshi? “Home is an inviolate space,” says Anmol Vellani, who adapted a 1967 English play 'Oldenberg' to a Tamilian household for 'Please Feel at Home'. “It is also a metaphor—about what we are making our home, namely our nation, into.”

As artists retell stories about long-lost homes, Bachelard muses if there is such a thing as a final home. “For a house that was final, one that stood in symmetrical relation to the house we were born in, would lead to thoughts—serious, sad thoughts—and not to dreams,” he writes. “It is better to live in a state of impermanence than in one of finality.”