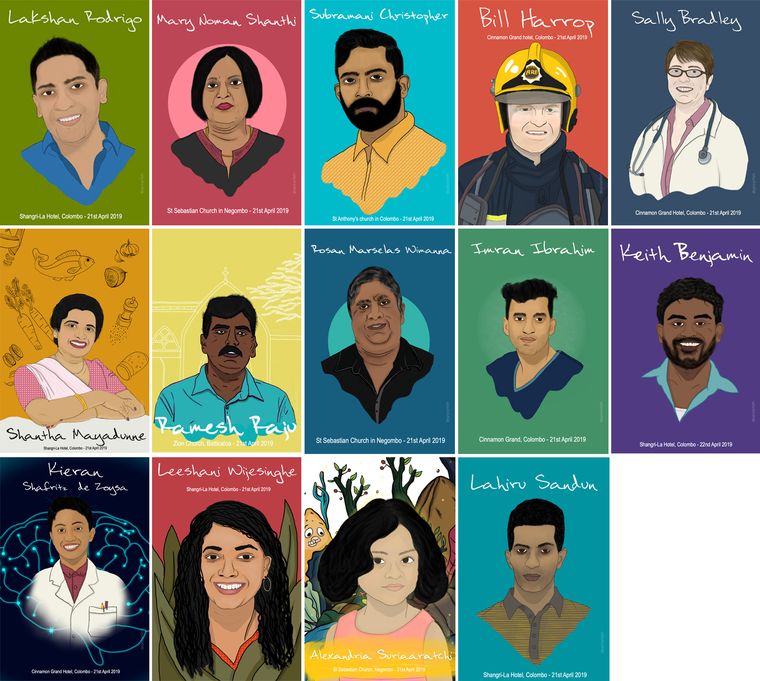

After the bombings that rocked Sri Lanka on Easter Sunday, social media erupted in anger. People everywhere came out with all guns blazing, against the perpetrators of the attack. In the ensuing frenzy, they almost forgot why they were angry. The 258 victims who lost their lives became a mere figure that leapt out of newspaper headlines. It was to humanise them, to give them back their identities, that 27-year-old Tahira Rifath, an illustrator from Colombo, decided to draw their portraits. “I wanted to bring the attention back to the victims,” she says. “They were people like you and me. They lived full lives and must have had aspirations and done incredible things. They were someone’s mother, father, partner, sibling or child.”

She began her first portrait on April 30, nine days after the attack, and has so far illustrated 24 victims using a software called Sketchbook Pro by Autodesk on her Mac. Along with the illustration, she gives a brief description of the person and posts it on Instagram. The backgrounds are always bright to show that they lived full lives. Rifath tries her best to incorporate a sense of who the person was through the images. To give them their individuality, she focuses on details like the kind of clothing they wore or the way they posed in photographs.

Her first illustration was of Ramesh Raju, a 40-year-old building contractor who was at Zion Church on that fateful day with his family. While in the courtyard, he noticed a stranger with a large backpack making his way to the church. After questioning him, he grew suspicious of the man and tried to force him to leave. That is when the man detonated the bomb. “If Ramesh had not done that, many more lives would have been lost,” says Rifath. “That is why I started with him. I wanted to pay tribute to the hero that he was.”

Initially, it was difficult for her to gather information about the victims. She had to depend mostly on social media to get their names. Then she would read news articles and research them online. She would verify the information through close friends or relatives. Ever since her illustrations have reached a wider audience and been shared on social media, people have been approaching her with stories and information.

According to Rifath, it was illustrating the children that was the hardest. Dulodh, for example, was just seven years old. His aunt says he was the kindest and most caring person she knew. She told Rifath that Dulodh’s mother does not know of his death because she herself is battling for life in a hospital. Then there is Keiran, a brilliant 11-year-old boy who wanted to be a neuroscientist when he grew up. As he was an only child, his mother had dedicated her whole life to his welfare.

The faces have definitely taken their toll on Rifath, especially as she has been grappling with depression and anxiety. “I kept complaining to my friends how I felt sad all the time and [often] burst into tears,” she says. In the first week that she started doing the illustrations, she kept going, ignoring her mental and emotional wellbeing, to the extent that she got sick. Now she makes sure she takes breaks in between. “If a story is really heart-breaking,” she says, “I try not to internalise it. I cry and get it out of my system.”