On September 16, surprise visitors came calling at Kalamwadi, a small village in Palghar district, 160km from Mumbai. Government officials, led by Maharashtra’s tribal development minister Vishnu Sawara, had come to offer their condolences to the family of Sagar Wagh, a two-year-old child who weighed 4.8kg and succumbed to malnutrition on August 28.

Government officials rarely visit Kalamwadi. Furious villagers, mostly tribals, heckled Sawara and refused him entry into their hamlet. “Where were you for the past six months when we needed the government’s help?” asked Sagar’s mother, Sita, angrily. “Just get out of here!” Sawara had no choice but to leave.

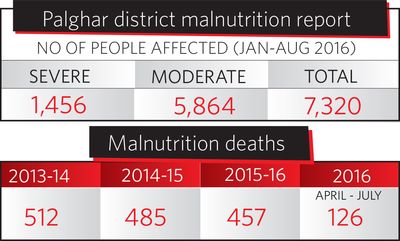

Since January, nearly 600 tribal children have died of malnutrition in Palghar district; more than 3,000 are being treated for it. “The government’s approach has been very passive and lethargic,” says RTI activist Hemant Patil. “The menace of malnutrition has been here for decades, but never have we seen such apathy.”

The tehsils of Mokhada, Jawhar and Wada in Palghar district are hilly regions of the Sahyadri ranges. The tribal hamlets here are difficult to access; most do not have proper roads. THE WEEK visited the home of 27-year-old Suman Dive, who lives with her husband, Tukaram, and their three children, in Shirasgaon, a remote village in Mokhada. Their 18-month-old daughter, Chitra, is undernourished and Suman does not have any food at home. Tukaram has gone in search of work and food. Their eldest son is 12 years old; Suman gave birth to him when she was 15. “Early marriages, undernourished mothers and poverty are the main reasons of malnutrition in this area,” says Vivek Pandit, a former MLA from the adjoining Vasai taluka. “Providing food security depends on the whims and fancies of the officials of the public distribution system (PDS) and shop owners. Politicians like Sawara simply do not bother.” Pandit runs free medical camps and social awareness programmes in these areas. “The root cause of malnourishment here is illiteracy and the lack of sources of livelihood,” he says. “Extreme poverty forces them to live on empty stomachs for days. Agriculture in these areas is totally monsoon-dependent and there is no work for eight months of the year.”

The tribals cultivate only paddy and ragi, and this option is available only to a few as most do not own land. Working as farm labour or daily-wage employees in nearby towns is their main source of livelihood.

Two weeks ago, three-year-old Jayashri Tobale was admitted to the primary health centre in Mokhada. The malnourished child weighed 9.3kg on admission and has gained 0.4kg thus far. “We have four sons, and Jayashri is our only daughter,” says her mother, Chaguna, 29. Her eldest son, Ankush, 14, works at a factory in a nearby town. “My husband, Bhagwan, and I work as farm labourers during the monsoons and as construction labourers for the rest of the time,” she says.

Recently, 150 malnourished children were in the health centre at the same time. “We had children from both categories of malnutrition: severe and moderate,” says Dr Mahesh Patil of the health centre. “Now, we have 10 patients and have adequate stock of medicines and nutritious food.” Since January, Palghar district has had 7,320 cases of malnutrition: 1,456 in the Severe Acute Malnourishment category and 5,864 in the Moderately Acute Malnourishment category.

Prevention is better than cure: Tribal school children wait for health checkups at the local hospital in Mokhada.

Prevention is better than cure: Tribal school children wait for health checkups at the local hospital in Mokhada.

Mangal Markar—whose malnourished four-year-old son is admitted at the centre—is one of the many villagers who migrate to bigger cities to find work. “Here, men get daily wages of Rs 150 and women get Rs 100, to work as farm labourers,” says Mangal. “In the cities, men get daily wages of Rs 350 and women get Rs 250, to work as construction labourers.” She complains that, many times, contractors in the cities make them work for 20 days at a go, but do not pay in the end. Says Changuti Male, 18: “I was once beaten up by a contractor when I demanded that my wages be paid daily. My two-year-old son, Shayaraj, weighs only 7.3kg and I cannot feed him as I am so weak myself.”

Pandit says the district needs massive awareness campaigns against early marriages and to promote family planning. Using the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) to generate employment and create irrigation infrastructure is the only way to eradicate poverty, he says. He has submitted a 17-page memorandum to Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis, suggesting permanent solutions for these chronic issues. “The CM agrees that measures taken by the government merely treat the symptoms and not the causes,” says Pandit.

The shortage of manpower in the departments concerned is also alarming. “In these areas, 50 per cent of posts of doctors are vacant. Dr Patil and other doctors literally live at the health centre,” says Pandit. “The child welfare officer of Palghar district doesn’t even have a vehicle to travel within the district for reviews. Every department has 50 to 90 per cent of vacancies.”

Sanskar Malekar, a malnourished child from Shirasgaon.

Sanskar Malekar, a malnourished child from Shirasgaon.

Sensitising people about malnutrition is crucial towards tackling the problem. “Countering malnutrition should be a long-term programme,” says Pandit. “The public, government officers and most politicians look at it as a work of rehabilitation. In September, when news about 600 children dying from malnutrition this year hit the front pages of the newspapers, political parties and NGOs flooded Mokhada with boxes of biscuits and mineral water.” These, however, are short-term solutions unlike creation of irrigation facilities.

Pandit calls the public distribution system inefficient and corrupt, and says the tribals have had to catch, fry and eat rats, as they did not get food for months. “It is time to issue food coupons or food stamps for tribals in remote areas which can be exchanged at local grocery shops,” he says.

On October 4, the Supreme Court rapped the Maharashtra government for its “lack of concern” over the deaths of children from malnutrition this year. “You don’t bother when children die. Your state is not taking any instructions from the government. Do you think we are wasting our time here?” asked the bench headed by Justice Madan B. Lokur. Strong words that will hopefully elicit the desired response.