On Friday, March 18, the Belgian police raided Rue de Quatre Vents in Molenbeek district of Brussels and, after a short gunfight, arrested Salah Abdeslam who had taken part in the Paris attacks on November 13.

Prime Minister Charles Michel thought the best way to celebrate the capture was to call French President Francois Hollande, who was already in Brussels for a European Union meeting, to a private viewing of the video of the raid. As the two were watching, came a call from President Barak Obama in Washington who complimented both. “We are celebrating a victory,” Michel told the press.

Spoken too soon! Within hours, Michel's sleuths had bad news. They reported that Salah Abdeslam had not just been lying low for the past three months in Molenbeek, but planning something sinister in Belgium. On Sunday, Michel's foreign minister Didier Reynders admitted as much in a panel discussion.

Most Belgians did not believe it. Though Belgium, particularly Molenbeek, was the hotbed of islamist extremists in Europe, they had never killed in Belgium. More than 400 Belgians have been estimated to have gone to Syria to fight on the side of Islamic State, and most of them had been schooled in religious extremism in Molenbeek, but none had ever pulled a trigger or a bomb fuse within Belgian territory. They had all been using Molenbeek as a safe haven where they could melt away into the large native and immigrant Muslim population, and travel in and out at will, thanks to the notoriously lax Belgian laws.

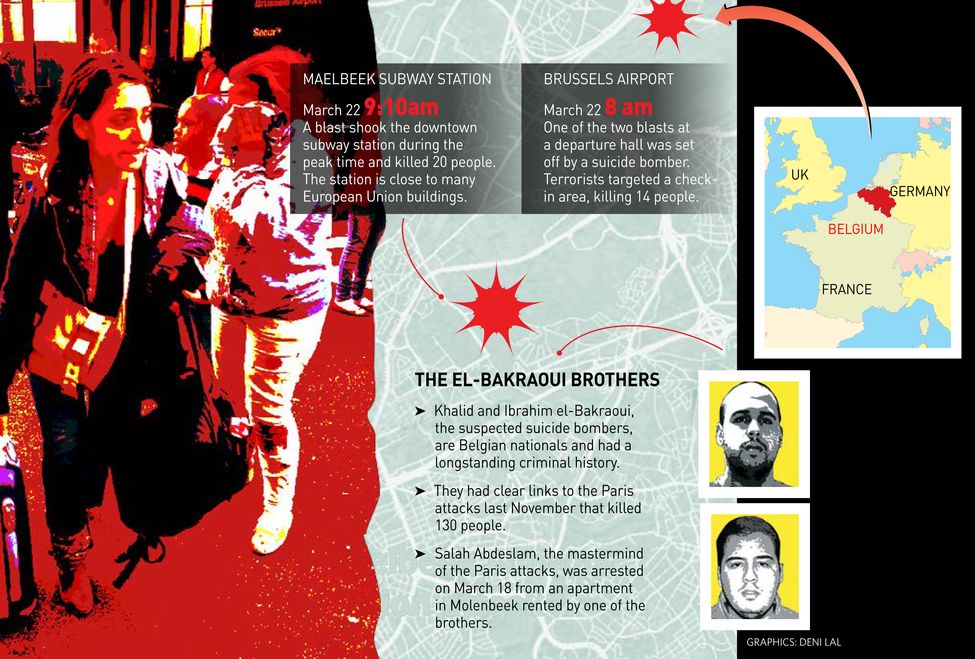

The fears came true within 48 hours. On Tuesday morning, bombs went off in the Brussels Airport and a metro station, killing 34 people and wounding more than a hundred. Terror had finally come home to Belgium.

To the political leaders of Europe, the attacks meant more. If the attacks on the swinging city of Paris had been viewed as attacks on Europe's civilisational values, the ones in Brussels were seen as a threat to the very idea of a political new Europe. “To you, here in Delhi, Brussels may not look as important as Paris, but it is different to us in Europe,” said a diplomat in the Delegation of the European Union in India. “As our leaders have said in their statement, our common European institutions are hosted in Brussels. We are attempting to build a new Europe from Brussels. Your prime minister [Narendra Modi] is visiting Brussels next week for the India-EU summit.”

The new Europe that its leaders have been trying to build is already under strain. Its member-states have accused each other of having been complacent about their immigration laws which allow terror-minded immigrants from Syria and elsewhere enter Europe and travel freely across its open borders. After the Paris attacks, some of them unilaterally put up check points on their borders, and some of these checks have been viewed as violative of the basic tenets of “open borders” and “liberal laws” with which the European Union is being built.

But then, the counter-argument is that it was the very basic tenet—of open borders and liberal laws—that enabled the enemies of Europe to walk in, kill and walk out. How Salah Abdeslam had escaped from Paris itself was a case in point. The morning after he took part in the November 13 massacre in Paris, he was driving back into Belgium when he was stopped on the border. They let him go, because there was no lookout notice at that hour!

Since then Salah Abdeslam was 'the one that got away'. It was believed that he had escaped to Syria, but the discovery of his fingerprints during a raid on a Brussels apartment on December 10 convinced the Belgian police that he was still in the city. The apartment was deserted, but the police found a suicide belt, and evidence that some explosives had been stored there earlier.

The next raid, on an apartment in Foret district of Brussels on March 15, yielded more. The apartment was occupied by Mohamad Belkaid, a Belgian of Algerian descent. He put up a gunfight before he was overpowered. Belkaid had travelled to Syria in April, 2014, and returned to serve Islamic State by running a sleeper cell.

He was doing his job well. Salah Abdeslam had actually slept in his house—the police found Abdeslam's fingerprints on a glass tumbler in the house. And in the next two days, they traced Abdeslam himself to Rue de Quatre Vents in Molenbeek, shot him in the limb and arrested him.

The French police, who don't have much of an opinion about the Belgian police, now say that Abdeslam had been staying in Brussels since November, and would have remained a free bird if he had not got active in the last few weeks. “Apparently, he was up to something in the last few days, and that is why the Belgians could pick up his scent somewhere—either his phone signals or some mail intercept or some unusual activity somewhere—and catch him,” said an officer in the Paris prosecutor's office. “But by the time he was caught, his accomplices would already have been on the job.”

The Belgian police have since flashed video images of three suspects, identified as brothers Khalid and Ibrahim El-Bakraoui and Najim Laachraoui, who were captured on the airport camera pushing trolleys with suspicious bags. The police are not sure if these men had killed themselves in the suicide bombing or simply left the airport after leaving the bomb-laden trolleys. Initial reports had suggested that one of the killers could be Abdeslam's friend Mohamed Abrini, 31, a Belgian of Moroccan origin who had travelled with him to Paris in November, but had not taken part in the actual attacks. He had apparently driven the attackers around in Paris on reconnaissance missions. But he does not figure in the images captured by the airport cameras.

Anyway, now the rest of Europe believes that Belgium will tighten its notoriously lax laws. Only a few weeks ago had Belgian authorities announced that they would recruit about 2,000 policemen, and mount closer surveillance on problem districts. The heat is already on Molenbeek, which has just about 90,000 residents, with nearly 70 per cent of them being migrant or native Muslims. The original natives were either European Muslims or Moroccan settlers who had welded well with the rest of Belgian society. Problems are said to have begun in the 1970s when capital-starved Belgium sought investments from Saudi Arabian businessmen. Fundamentalist preachers who came with them built mosques and have since converted the people largely of Moroccan descent to radical Islam.

Belgium's federal system is also to blame. It is layered in such a way that there is too much of duplicity of authority and anyone who wants to slip away from law can easily disappear here.

Traditional attitudes of policing and intelligence gathering are also to blame. The state system in Belgium is still largely European-staffed; most officers, both civil and police, are ethnic Europeans. As there are very few Muslims in the organs of the state, including the intelligence agencies, the state suffers from severe handicaps in penetrating the community.