At the entrance of the Hasan Shame refugee camp, 20 kilometres east of Mosul in northern Iraq, women fleeing Islamic State remove their niqabs and burqas and hang them on a wire fence. Families torn apart by war are regrouping for the first time in two years. Sisters, brothers and cousins embrace in tears. Many of them had lost contact with each other, while the lucky ones were able to hide cellphones in holes dug into the floors of their homes.

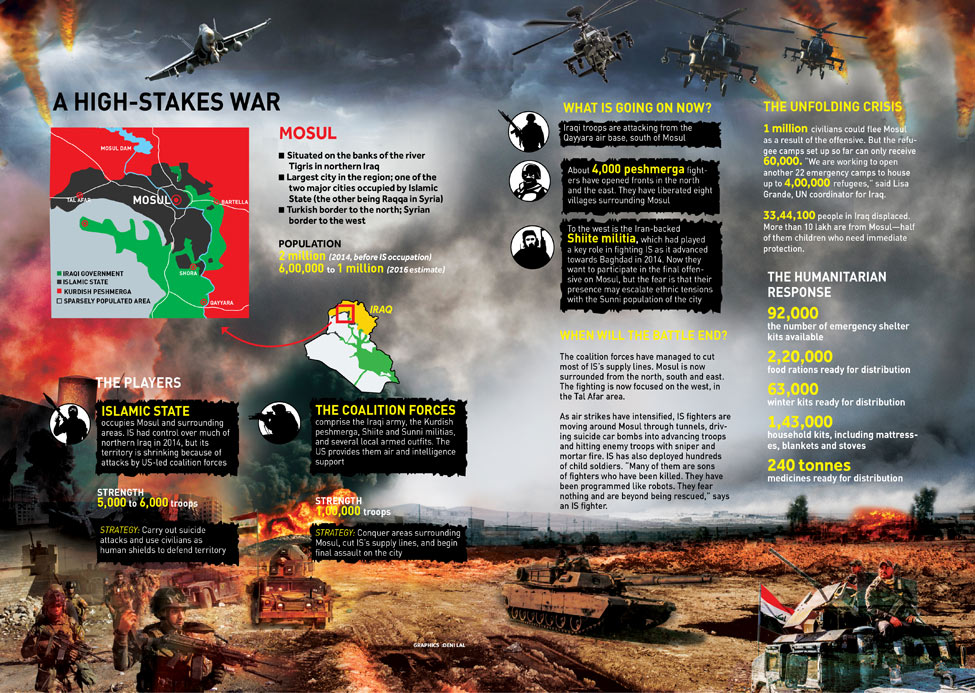

The US-led offensive on Mosul, the last major stronghold of IS in Iraq, began on October 17. As Iraq’s second largest city, Mosul once housed Kurds, Sunni and Shia Muslims and Christians. With most of its residents either displaced or being held to ransom by IS, the city is at the centre of a humanitarian crisis. Relief organisations expect the offensive to create at least one million internal refugees, which will add to the 3.3 million who have already been displaced.

The fate of all of them is in the hands of a mosaic of forces that today are fighting, apparently, for a common cause: the Iraqi army, the Kurdish peshmerga, the Shiite militia Hashed al Shabi, the most dangerous in the field, and several other local militias, each ready to claim their own power.

It was in June 2014 that IS captured Mosul, forcing two Iraqi army divisions to flee the city they were supposed to defend. In two years, IS imposed sharia on the city’s population, forced thousands of Christians to flee their homes, confiscated their money, destroyed their churches and executed all Sunni and Shiite opponents. During his recent visit to Iraq, Filippo Grandi, UN high commissioner for refugees, termed the protection of civilians as the most important component of the military operation to liberate Mosul. The high commissioner’s office will need at least $200 million to effectively deal with the crisis at hand. At the moment, though, funds at its disposal do not exceed 38 per cent of the figure.

Meanwhile, in Iraqi Kurdistan, new refugee camps are springing up: One of them is Al Khazir, east of Mosul and near Bartella, one of the Christian villages recently liberated by the allied forces. Shaker Khalifa arrived at the camp a week ago with his wife and two children—a teenager and a four-year-old. He comes from Tob Zawa, a village near Mosul. Shaker takes a cigarette from his pocket and smiles. “I could not smoke for two years,” he says. “At the beginning, they fined us 3,00,000 Iraqi dinars if they found us smoking. Then they started corporal punishment and arrests. They even forced us to throw out all our clothes, not accepting signs in English or drawings they thought were blasphemous. They destroyed TVs, phones and all other electronic devices. They wanted to prevent any contact with the outside world and make sure that the only reality we could know was their distorted reality. Above all, they wanted to prevent our children access a world different from their own, so that the brainwashing of their minds became easier.”

In good faith: A bishop greets an Iraqi soldier near the Bartella front line.

In good faith: A bishop greets an Iraqi soldier near the Bartella front line.

In Tob Zawa, Shaker had a shop where he sold perfumes and detergents. Initially, IS members told him to pay a monthly fee. Then they forced him to close it down, because the sale of perfumes was forbidden as per their interpretation of sharia. “I did not know how to feed my family,” he says. “I gave them all of my wife’s jewellery for a few thousand dinars. I could not run away. For a long time, because of the mere fact of having lived under IS, we carried the burden of stigma and we feared retaliation. Living there or elsewhere for us represented the same danger.”

The first two sons of Shaker escaped to Erbil in 2014. Ashraf, the third, was a teenager. His school, like all others in the region, was closed. Ashraf said that every Friday, IS members went from one house to another, gathering children for sessions at the mosque. They wanted to recruit children for the cause of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, IS chief and self-proclaimed caliph. Those who refused were dragged to the streets and whipped in public.

An Iraqi soldier gives water to a captured IS fighter.

An Iraqi soldier gives water to a captured IS fighter.

One night, after the beginning of the offensive on October 17, IS members knocked on Shaker’s door, seeking Ashraf because someone had told them that he was a peshmerga spy. “They tied my hands behind my back, blindfolded me and loaded me on to a car,” says Ashraf. “They took me to one of the tunnels they had built in the village.”

Inside there were weapons and material to build bombs. There were also beds, food and medical supplies. “I thought those men could have lived there for weeks,” he says. “They forced me into one of these tunnels to question me.”

Someone informed the IS intelligence that Ashraf’s brothers had joined the peshmerga to fight and defeat al-Baghdadi. “I kept crying and screaming that it was not true, that none of my family was fighting against them. They tortured me for hours with electric cables and whips,” says Ashraf. Shaker says that when Ashraf was finally released, his back resembled a map drawn of blood and wounds.

Hope springs eternal: Girls pray at a makeshift prayer room at a shopping mall in Erbil.

Hope springs eternal: Girls pray at a makeshift prayer room at a shopping mall in Erbil.

Those days, people living under IS feared of being punished, detained or killed. Today, weeks after the beginning of the offensive, the fear has been replaced by a dilemma: whether to stay at home with the risk of being held to ransom as human shields, or to get away and risk death by sniper fire or by the hundreds of mines left by IS.

Not all people in refugee camps have stories of suspicion and fear to tell. For many of them, life under IS represented, at least initially, a more dignified existence than that guaranteed by the government led by Nouri al-Maliki. Mahkmoud, the eldest among the thousands of newcomers from Tob Zawa, sits outside his tent. Around him are dozens of men from his village. “In the beginning, IS members came to us and promised a better life, saying they wanted to protect the real Islam, showing themselves as liberators and friends,” he says. “They paid our boys 1,00,000 Iraqi dinars a month, and they took grain and bread to all the families in need.”

Mahkmoud was wealthy. He had a farm in the village, and 10 per cent of his earnings every month went to IS. Initially, he willingly gave the money to support IS; later, unwillingly, to quell his fear of being killed. Mahkmoud described a life of deprivations, but with an initial, apparent stability. “I had no choice,” he says. “For a time, I thought it was for a good cause, for the well-being that these men promised to bring to my people. They distributed all properties and goods confiscated from Christian villages. I thought that if we did not violate their laws, we could live in dignity. I thought: my life under IS cannot be worse than the one the government had reserved for me.”

Then things changed. IS increased taxes and decreased wages, and consensus began to wane. And the more the consensus waned, the more brutal became the punishments. Repression became the watchword.

Karam el Hiam of Tob Zawa had a computer store that also sold electronic games. IS forced him to shut it down and destroyed all his belongings. Four months ago, his cousin was caught with a phone. The Hasbah, IS’s ruthless police, tore her nails one by one. Then they killed her.

The Dibaga refugee camp, on the outskirts of Erbil, is a vast expanse of tents. With a capacity to accommodate no more than 28,000 people, it is now home to 40,000. In some cases, three families live in a tent; those who have no place in the tents sleep on the ground outside.

The Dibaga refugee camp, which houses about 40,000 people.

The Dibaga refugee camp, which houses about 40,000 people.

Water is scarce and there are not enough toilets. Food is a luxury. “The hygienic conditions are worrying, especially for women, who have, in these two years, been forced into a life of segregation and violence,” says Giulia Cappellazzi, head of Mission of Un Ponte Per (A Bridge for) in Iraq. “We have heard hundreds of stories of abused women [who were] forced to give up their lives and remain locked in the house, fearing for their husbands and children. We believe it is necessary to help these women overcome the trauma.”

Women struggle to talk even with psychologists: they are afraid of retaliation, since many of their relatives are still in Mosul and surrounding villages. They fear to show even their eyes under the niqab. Fatimah (who does not want to reveal her real name) is 25 years old. She is two months pregnant and walked seven hours to get to the safety of the Dibaga camp.

All is not lost: Families fleeing Mosul at night.

All is not lost: Families fleeing Mosul at night.

One night, a few months ago, IS members arrested her husband and father, a former Iraqi policeman, and took them to jail. Accused of being spies of the Iraqi army, they were tortured and hung from the ceiling for two days. Before they were let go, IS confiscated all their property.

Her father is no longer able to move his hands. Her husband often wakes up in the middle of the night, screaming. “I was not used to wearing burqas, but the real shock for me was the imposition of the gloves,” says Fatimah. “One day I looked in the mirror and did not recognise the reflection on it. I did not know who was the woman hidden by the black cloak. I could not leave home unless accompanied by a first-degree relative. We were forbidden to study, to work. Even thinking was forbidden. They did not want citizens. They were only looking for soldiers willing to die.”

Fatimah managed to escape on a Friday “during prayer, because it was not easy to find them in the street, they were all in the mosque”. “When I left home, I was sure to die. Being here is a gift,” she says.

Refugees at Hasan Shame camp queuing up for food.

Refugees at Hasan Shame camp queuing up for food.

Aicha (name changed) is 40 years old and a mother of four children. One of her children died three years ago, when her house was set on fire by a fundamentalist group in her Bir Halan village. “In the village, everyone knew the most extreme families around us, and when men from Tikrit and Anbar arrived at Bir Halan, we called them ‘bad tourists’,” says Aicha. “At that time, my husband worked for the Iraqi police and they threatened him constantly. One day, they went to his office because they wanted to turn it into an office for the Islamic police. They ordered him to leave the office and never return. My husband refused. I was in the market buying something for lunch when a neighbour called me shouting that my house was on fire. I ran as fast as I could. My child was inside, sleeping. I tried to walk in the flames that enveloped my house to save him.”

Aicha’s son died in the flames. The ‘bad tourists’ became Islamic State.

Sadi Yusef Latif, 23, lived in Qayyara under IS for two years. His dream was to become a doctor, but he now lives in Jadaa refugee camp. He would like to wash and put on clean clothes, but there are none.

His cousin, Ibrahim, 19, was an asthma patient. One day, Yusef went with him to the Qayyara hospital to buy medicines. But IS members refused to oblige, because not all members of Ibrahim’s family were IS supporters. The few medicines left in the city were guaranteed only to the families faithful to al-Baghdadi. The others were left to die.

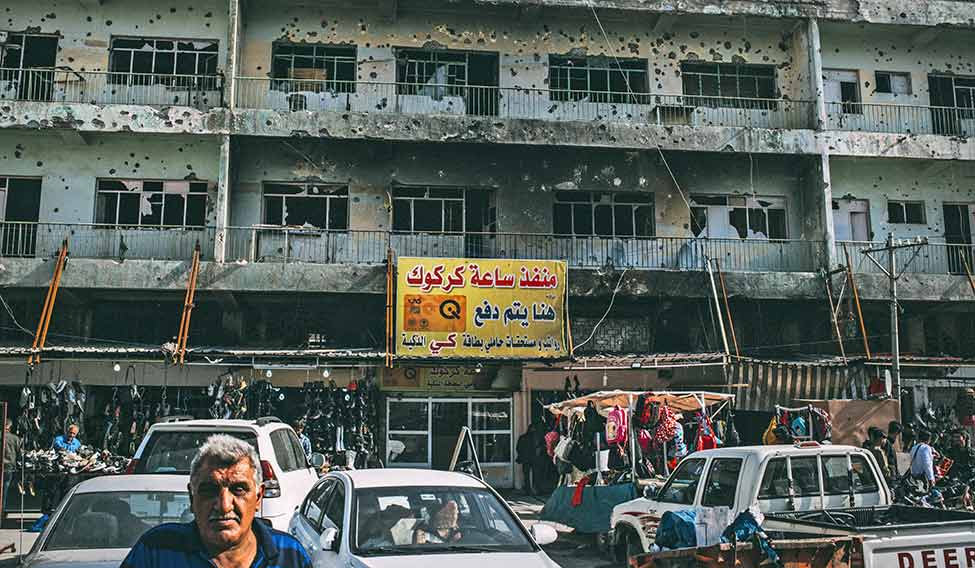

GUNFIRE AND BRIMSTONE: These battered walls in Kirkuk city say a long story. A story of fortitude. Even as the Battle for Mosul raged, IS snipers unleashed terror from this building—clearly a diversionary tactic. The frustrated Iraqi-led coalition soldiers engaged in a long gun-battle to snuff the jihadists out.

GUNFIRE AND BRIMSTONE: These battered walls in Kirkuk city say a long story. A story of fortitude. Even as the Battle for Mosul raged, IS snipers unleashed terror from this building—clearly a diversionary tactic. The frustrated Iraqi-led coalition soldiers engaged in a long gun-battle to snuff the jihadists out.

Indeed, Ibrahim died soon, and Yusef decided it was best to try to escape than die under Islamic State. “I knew there was one man in town who helped civilians escape, a source of the Iraqi army. So, one day, he took me home, hid me for a few hours until he received a call from his friend in the Iraqi police, and then helped me escape. I paid $200 for this. I was lucky; in some villages they were demanding $1,000.” According to the UN, since the beginning of military operations, summary executions of fleeing civilians have multiplied in the villages still under the control of IS.

According to reports, IS has executed 230 people, including 190 former members of the Iraqi army, at al-Ghaslani military base. As the battle for Mosul enters a decisive phase, hundreds of families have been forced to move into the town from surrounding villages to be used as human shields. The bodies of executed civilians are piled in the square and streets of the suburbs and neighbouring villages.

The battle of Mosul will be tough and bloody, as IS had time to turn the city into a trap made of chemical weapons, suicide bombers and snipers scattered everywhere.

The blood price of this urban war will be very high. IS knows it cannot win this war, but the fidayeen are determined to make it very painful.

Recently, in the refugee camp at al Khazir, two girls arrived from a village near Mosul. One of them was injured by a mine. One of the hundreds of mines scattered by IS around the villages.

Going to die and punish, the watchwords of today.

Reprisals, possibly, that of tomorrow.