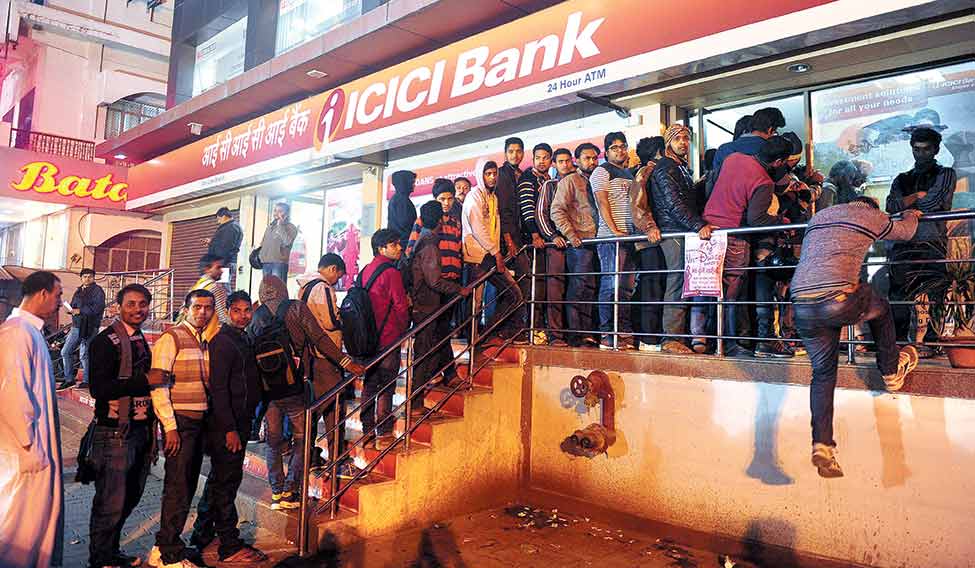

Last November, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced demonetisation of 1,000-rupee and 500-rupee notes, he said the intention was to weed out corruption and black money from the economy. Some 80 people reportedly died in the problems caused by a severe shortage of cash across India. The BJP called it a great sacrifice to rid the economy of the two evils. It paid—the party swept the assembly polls in Uttar Pradesh four months later.

It has not been as rewarding for many others, especially the labour-intensive small and medium enterprises. “Closure of units was common during demonetisation,” said Anil Bhardwaj, secretary general, Federation of Medium and Small Enterprises. “Because of the cash crunch we ran shifts with half the number of workers and produced less till cash flow normalised. By then more than half the workers had taken off from the cities and some are yet to return.”

It did not help that the government came up with stricter directives on accepting the old notes and issuing fresh ones. “Initial days of demonetisation were horror,” said banker Uday Kotak at a discussion hosted by Confederation of Indian Industry in Delhi. “I recall the government would issue notifications with new rules every day as an afterthought to the announcement. For us banks and thousands of bank staffers, it was a daily nightmare.”

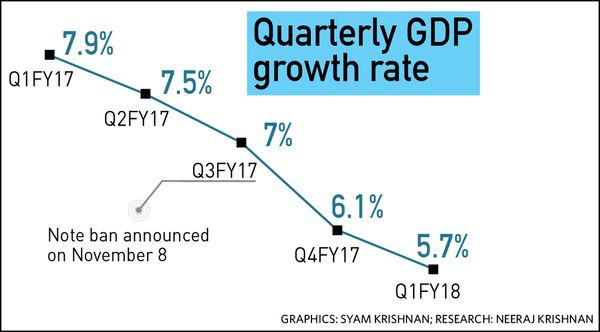

It continues to be one for the economy. In July, former prime minister Manmohan Singh said in the Rajya Sabha: “My own feeling is that the national income, that is the GDP, can decline by about 2 per cent as a result of what has been done. This is an underestimate, not an overestimate.” His apprehensions turned true a month later, when the GDP growth rate for the March-May quarter, at 5.7 per cent, was reported to be lowest in three years. It was 7.9 per cent in the same period last year. “The main impact is due to the drop in industrial activities and a drop in domestic savings,” said chief statistician T.C.A. Anant, while releasing the numbers on August 31.

When the RBI revealed in its annual report for 2016-17 that it had received about 99 per cent of the demonetised currency notes, hopes of large amounts of cash recovery were dashed. But the finance ministry saw it as an opportunity. “The government had expected all the SBNs (specified bank notes) to come back to the banking system to become effectively usable currency,” said Finance Minister Arun Jaitley. “The fact that the bulk of SBNs have come back shows that the banking system and the RBI were able to effectively respond to the challenge of collecting such a large number of SBNs in a limited time.”

In December last year, however, the finance ministry's 'expectation' was quite different. At that time, revenue secretary Hasmukh Adhia would brief journalists about the initiation of Operation Clean Money. The money that did not come back to the system, he would explain, was effectively the black money that had been purged out of the economy. But, now that just around 1 per cent of the money (Rs 16,230 crore) did not come back, the RBI's hopes of a fiscal windfall have been dashed.

In fact, in addition to the administrative expenses, printing of new notes and arranging for their logistics put a dent on the RBI's profit. The dividend it paid to the government came down from Rs 65,896 crore last year to Rs 30,569 crore this year. “Given the cost of the demonetisation drive, if the government now says that it has detected only Rs 16,000 crore in black money, it perhaps defeats the purpose,” said macroeconomist Laveesh Bhandari, director, Indicus Analytics. According to him, the loss of Rs 35,200 crore revenue to government is just the monetary cost of demonetisation. “The real cost would have to be the GDP loss caused by job loss and other collateral damage to the economy due to demonetisation,” he said.

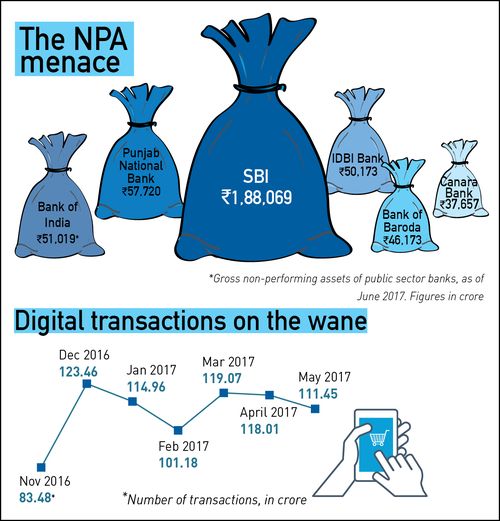

The problems of demonetisation have been everywhere. “We cannot see even a modicum of improvement in private investment activities as of yet,” said Aditi Nayar, principal economist at the ratings agency ICRA. “The lull in investments after demonetisation is not quite over. We expect this lull to continue over the next three or four quarters until domestic as well as global business environment improves.” Not just private investments, but trade, too, has suffered. The only ‘green shoot’, according to Nayar, is the spike in public investment in the form of infrastructure projects. “But government spending also has its limitations and we expect this to taper down in the coming quarters,” she said.

All three stated objectives of the demonetisation—elimination of black money, ending corruption and chocking terrorism funding—have so far yielded mixed results. So did detection of fake currency notes, which was one of the primary objectives when demonetisation was first proposed by a right-wing organisation in 2013. In a written reply to a question in the Lok Sabha, Jaitley said that, post-demonetisation, fake currency worth Rs 11.23 crore was detected from 29 states—just a fraction of Rs 1.23 lakh crore expected to be in circulation by the RBI. “Fake currency notes of new Rs 2,000 and Rs 500 were available in the black market. As people toiled for currency, these fake notes filled the gap,” said Sarbajit Roy, convener of India Against Corruption, which supported demonetisation in the beginning. He said it was ill-conceived by the RBI and the government.

Most of the important sectors have been hit by the demonetisation. The services index became negative for first time in past two decades and the manufacturing index hit the lowest in a decade. Employment generation fell to less than half of the target because of the slow economic activity. International Monetary Fund, which praised Modi for the demonetisation drive, has now cut India’s GDP growth forecast for the current fiscal by more than half a percentage.

“The main worry remains that sectors that have a high potential to absorb labour force have seen the sharpest dip after demonetisation. Some sectors which grew fast in this nine-month period had low labour intensity and low share in overall output. This suggests that slower economic growth resulted by demonetisation could also have shaved off employment growth in the economy,” said Dharmakirti Joshi, chief economist of the rating agency CRISIL.

And, the benefits? The benefits of demonetisation to the economy are in the form of digitisation, according to Arvind Subramanian, chief economic adviser to the government. “Demonetisation has given a huge boost to digitisation. We found that it could have added 20 per cent new tax payers to the tax base,” he said, releasing the part two of the Economic Survey for the year in August. He said around 5.4 lakh new tax payers had been added over the last year. The additional tax revenue due to this, however, would remain limited. “We see most of these new tax payers are declaring incomes at the tax threshold, and either not paying income tax or paying a nominal amount as income tax,” he said.

A statement from the finance ministry, however, said the demonetisation had a positive effect on tax collection. “Collection of Advance Tax under Personal Income Tax (i.e. other than Corporate Tax) as on 05.08.2017 showed a growth of about 41.79 per cent over the corresponding period in F.Y. 2016-2017. Collection of Self-Assessment Tax under Personal Income Tax showed a growth of 34.25 per cent over the corresponding period in F.Y. 2016-2017,” it said.

The finance ministry recently said that it witnessed a 38 per cent increase in admission of undisclosed income, and the searches and seizures had doubled post-demonetisation. “High-, medium- and low-risk cases have been identified through use of advanced data analytics, including integration of data sources, relationship clustering and fund tracking,” said Adhia. “Operation Clean Money in its second phase has detected about 14,000 property transactions of more than Rs 1 crore each where persons have not even filed income tax returns. The investigations are in progress.”

The SMEs expect the government to fix the mess it created. “Demonetisation may have hit us hard. But we wanted to show resilience and get back to normal activity. However, this will not be possible without the government announcing any real fiscal benefit for the small and medium sector that employs 70 per cent of the labour force. In the budget after demonetisation, some very small benefits were announced, but it is clearly not enough,” said Bhardwaj. According to him, it is now for the government to take some corrective actions in the next budget.