Hum logon ko samajh sako toh samjho dilbar jaani, jitna bhi tum samjhoge utni hogi hairani... (Try figuring us out, the more you understand us, the more perplexed you'll be), wrote noted lyricist Javed Akhtar, as he went on to elaborate Indian idiosyncrasies in a catchy number that is often played during the sundown ceremony at Wagah border and at a zillion other jingoistic platforms.

Illustrations: Jairaj T.G and Deni lal

Illustrations: Jairaj T.G and Deni lal

All people are strange when viewed through the lens of another culture. However, when the culture itself is a mishmash of several influences―an ancient philosophy as vibrant today as it was in the Vedic age, centuries of invasions and subjugation, an inherent resilience that somehow absorbs completely alien concepts and yet doesn't dilute its own―what you get is a heady broth whose ingredients aren't easy to identify. Factor into this the rapid social change―from a colonial past through a socialist upbringing and now steeped in a capitalist market economy, all under the span of a century. Is it any surprise that Indian behaviour is mind-boggling even to Indians?

We have devised a beautiful line in Indian English to explain ourselves―we are like this only. It has taken us time, however, to define ourselves this way and, in a sense, even take pride in it. For it took time to get over the embarrassment of a colonial past that left us with a huge inferiority complex. It also took time to forge an Indian identity out of the smorgasbord of castes, communities, states and languages that restrained us. We are still identified by each of these divisions but, above that, we are also defined by our peculiar Indianness―an integration neither the Constitution nor politicians could bring about, but which Indian cinema helped forge. “It's only the current generation which is completely at ease with its Indian identity and actually revels in it,” says ad-filmmaker Prahlad Kakkar.

THE WEEK embarked upon an ambitious project, to figure out just why we are what we are. “Whoa, for 2,000 years people have been trying to answer this and yet they have not come up with all the answers,” said H. Kishie Singh, columnist and automobile expert, as he joined us in finding some answers. “We have got this tendency to be overly critical about our behaviour and we see our Indianness out of context. Why, for instance, should we define ourselves by some western parameters of behaviour?” asks mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik. “Ours is a country where scarcity exists even today. The west screws up its nose in distaste as Indians relieve themselves in public. The reality is there aren't enough toilets for everyone. And many men, who have not used a proper toilet, don't know the first thing about using a flush.”

Indeed, harsh realities have forged our behaviour, but not all explanations come from scarcity. Some stem from a culture which is not prescriptive and where there are multiple levels of acceptance. Where nothing is defined as black or white, but by many subtle hues, with as many interpretations as there are people. The gods themselves gamble, chase nubile maidens and drink copious amounts of liquor. “At the micro level, we may be seen as intolerant, fundamentalist people who beat maidservants and torture hapless people. But, on a bigger level, we accept everything, perhaps which is why we condone so many social evils, too,” says psychiatrist Harish Shetty.

So, while we will never find completely satisfactory answers to the question, here is a small attempt.

TIMELESS CLASSIC

An investment banker from India was five minutes late for an appointment with his clients in a Zurich restaurant. His clients had left. The banker learnt that in clockwork precise Switzerland, every second counts, and being late for a meeting is a terrible insult. Well chastised, he arrived a little earlier for his next appointment. But the Swiss were equally disapproving. Didn't he have faith in the punctuality of the Swiss public transport system that he had to factor in extra time?

The banker has now understood the finer nuances of Swiss time but, whenever in India, he loves the luxury of easing into the Indian Stretchable Time. “We are in time, isn't that enough. We don't have to be on time, too,” says Shetty with a chuckle.

So why is it that Indians, apart from faujis (soldiers, who wear punctuality on their sleeves, as if their wrists weren't enough), can never be on time? Researchers will tell you there are two types of latecomers. The first are people who never get a grip over time management and cram in too many unscheduled chores into a fixed routine. Then they are left wondering why that little detour to the grocer ate up over half an hour. They had not factored in traffic or parking time. These, we call the apologetic latecomers.

Most Indians, however, fall in the other category, the deliberately late. They are late because they are afraid to be early. Afraid they will punch in before the set office time and, worse, have no one around to see them in this act of virtuosity. It is different from working late, you get a badge of honour for that. In India, we know punctuality doesn't pay.

The Indian genius, however, isn’t the type to merely succumb to a fear. It has worked upon the fear till it has become a piece of art. A groom who reaches at the appointed hour (time printed on wedding card) causes social embarrassment. The importance of a person is directly proportional to how late he or she arrives. Divas are not made by being the first to an event―they patiently wait for the gathering to build up before making their wow entry. And, how can any mantriji reach on time? It will be doubly disastrous, proving that not only is he unimportant, but also that his schedule is bare. And, what is a public that doesn’t take cue from its leaders? So, learn to be not on time, just in case you had other ideas in your head.

Did someone just say something about wasting time? Aah, that someone doesn’t know that in India, we don’t waste anything, even time. It is recycled. Yes, unlike the linear idea that the west espouses, time in India is cyclic. Samay is depicted as chakra, not a timeline.

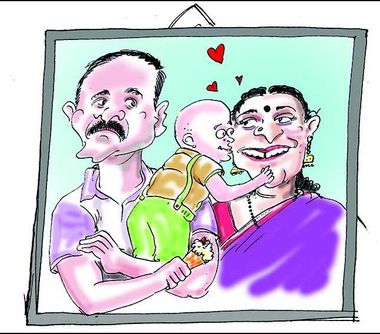

MAMMA'S BOYS

Here is an interesting conversation overheard while waiting for a visa at the US embassy. “You are going to the US with your mother, is that right?” asked the visa official. “Yes,” replied a 30-something Indian male. “Where?” barked the official. “Vegas,” replied desi boy. “You serious, you're going to Vegas with your mother. Did I hear that right?” asked the incredulous official. The mamma's boy, with matching incredulity, asked, “Yes, why not?”

The official did stamp his visa, muttering at the strangeness of people. None of those in the waiting room, however, found anything strange. In all probability, they may have had relatives in Vegas. But while a man from another country would have made that position clear first, the Indian man saw no reason to. He had his maa with him, what else does a man need? Didn't A.R. Rahman take his mother to the Oscars and quote the famous Bollywood line “Mere paas maa hai [My mother is with me].”

Mothers and sons have a special bond, that is a universal truth. In India, however, this bond overwhelms other relationships to the extent that even alpha males wear their mother's love as a badge of honour. Prime Minister Narendra Modi's first step in international diplomacy was sending a shawl to his Pakistani counterpart Nawaz Sharif's ammi. The significance of the gesture was clearly understood across the border for, when it comes to mother fixation, we are still one people. Nawaaz miyan's ammi promptly sent a sari for Modi's ba and thus it was established that the two leaders were on equal footing.

A few months later, Modi announced to the world that there was never any doubt about the success of India's Mars mission. It was named MOM (Mars Orbiter Mission) and a mom never fails.

Shobhaa De once wrote: “Men love their mothers. Men only love their mothers. Men love their mothers only.” This pretty much sums up the Indian male's fixation. Aah, just in case you feel that your man isn't a mamma's boy, De added that some men just hide their feelings better than others. “Yes, I am a mamma's boy,” asserts columnist and satirist Kunal Vijaykar. “But at least I am unmarried,” he grins, knowing too well that marital status doesn't really change this fact.

In the tough choice between being mamma's boys and henpecked husbands, Indian males perhaps feel the former conforms more with their supposed macho persona. “In the patriarchal, chauvinist setup we have, a mother's love for her son is overwhelming, so the male dependency on his mother is huge,” says Vijaykar. “His mother is his goddess, fulfilling his every wish, protecting him from all evil. In her eyes, he can do no wrong. Where else will you get such unstinting love?” The father may bring home the bread and bacon, but it's the mother who lovingly feeds these portions to her son, often depriving herself. Indian films have, of course, performed yeoman service in elevating the mother-son bond to something divine. A wife's love weakens him, the mother's only gives him strength. That's the message, writ clearly across every formula film.

From the mother's perspective, the son brings the woman a level of acceptability and approval within the family that a dozen daughters cannot. So, she tightens the bonds of love around him, refusing to let any other woman into the competition. “So, every Indian wants his wife to be in his mother's mould,” says Vijaykar. That she never is remains another universal truth.

One husband we know is still scratching his head wondering why his wife stomped out of the room when he said the halwa she had made was just like the one maa made. He had given her the ultimate compliment, hadn't he?

QUESTIONING QUEUES

Have you heard this one? Operator: Aap kataar mein hai... (You are in queue, please wait), Caller: Not Qatar, I am in India. Which obviously means, “I will not wait in queue.”

Why are we so averse to queues? Well, for starters, queues are not fair. There is a distinct class system of VIP queues, whether for a darshan at a temple or for rice at the ration shop, notes sociologist Shiv Visvanathan. Add to that collective memories of past scarcity, when getting landline connections took years of waiting and those foolish enough to wait like good boys returned home without kerosene every month.

So, we have a Pavlovian conditioning to rush out and grab, even if the approaching bus is empty. And if at all we have to be in queue, it has to be on our terms. Just as Amitabh Bachchan said in Kaalia, “Hum jahan khade ho jaate hai line wahin se shuru hoti hai [the queue starts from where I stand].” Above all, there is the great Indian reality that it pays to subvert rules. For when the unofficial queue gathers critical mass, the authorities, more often than not, legitimise it. And, if you haven't been smart enough to align yourself with the breakaway faction, your waiting time doubles.

This leaves behind those, who, for some inexplicable reason, are left standing on the straight and narrow queue. They stand impatiently, pushing those in front with their paunches and elbows, irrationally believing this momentum will help move the queue faster.

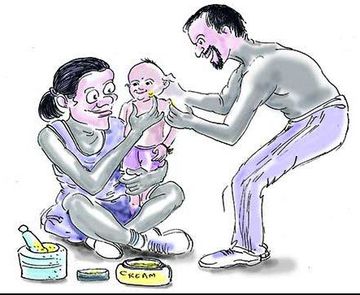

ONLY FAIR IS LOVELY

The Indian skin―firm, smooth, blemishless, pleasant to the eye, afraid of no colour, harmonising with all colours and adding grace to them all. I think there is no chance for the average white complexion against that rich and perfect tint. Mark Twain was a fan of the Indian complexion, and used eloquent prose to describe it. The Indian fixation with white skin is another story and the twain outlooks shall never meet.

Parents with dark complexions bemoan the birth of a daughter as dark as them, then resort to scrubbing the infant with flour, milk, turmeric and a host of unguents to lighten the skin. As the child grows, she reaches out for fairness creams, bleaches and talcum powders, the result of which leaves a face two tones lighter than the rest of her dark torso. The dusky beauty looks hideous now, but she doesn't care. She is fairer now, and gets some self-confidence. That's all that matters. A wise Bengali once said Gorang sorbotra joi (the white complexioned always triumphs), and most Indians concur.

Amid all the critique that Leslee Udwin's film on the Delhi gang rape of 2012 elicited, commentator R. Jagannathan's observation stands out. “What bothers me … is that government gives permissions (to BBC, to interview the accused in jail) it won't give to locals. Colour of skin matters?” he tweeted.

According to Amish Tripathi, creator of the Shiva trilogy, the Indian obsession with fair skin is the result of serial invasions by whiter people―Turks, Persians and Europeans. “In ancient texts, there are no references to the colour of the skin―either fair or dark―as a marker of beauty,” he says. Indeed, Draupadi, also known as Krishna for her darker than normal complexion, was hailed as a phenomenal beauty, and fair-skinned gods like Shiva were considered equally good looking. “Shiva is described in the Yajur Veda as karpur gauram or white as camphor. The modern elite conceptualisation of Shiva as a dark-skinned aboriginal deity before the so called Aryan invasion is incorrect,” says Amish.

Yet, by the time one comes to medieval ballads of Padmini, the famous Chittor queen who committed jauhar (suicide when facing defeat at the enemy's hands), she is described in this improbable way―Padmini was so fair, her skin was translucent. When she swallowed the red juice of the paan, one could see it course down her throat. Elsewhere, such pigment deficiency would be cause for concern; here, it was the epitome of beauty.

Years of subjugation by the English only refined the white supremacy complex among Indians; even Raja Ravi Varma's Renaissance-inspired paintings depict the divine as milky white. Then came Amar Chitra Katha comics, all depicting asuras as dark and horned. So, even as Indians refused to play cricket with South Africa while they practised apartheid, we didn't flinch at the unofficial apartheid back home. In fact, we monetised it, starting a thriving industry of whitening products.

Amish believes that once Indians get over the white skin obsession, we will break free of the Stockholm Syndrome. But Stockholm is in a white country, isn't it, so why would we want to break out of its syndrome?

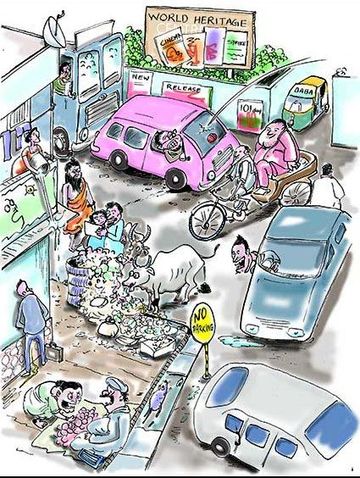

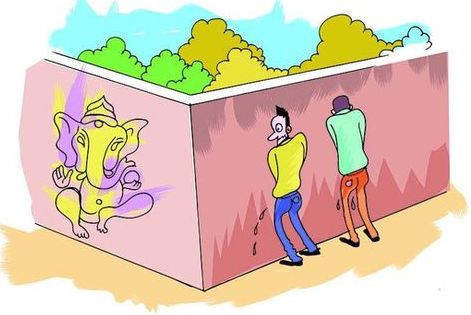

NO CIVIC SENSE

There was a wall outside Mumbai’s Sassoon Docks which reeked worse than the fish within the docks. For some reason, men gravitated towards this wall to relieve themselves. No amount of notices would deter them, even graffiti ridiculing them as donkeys had no effect. Then someone hit upon a bright idea. Armed with pots of paint, he proceeded to give the urine soaked wall a divine makeover. Soon, deities of every religion, from Ganapati to Guru Nanak, appeared on the wall and the stench dissipated. The toilet goers sought out another wall to drench. Even the sweeper moved the garbage to another spot.

The sacred has a grip over Indians that civic rules can never compete with. This, perhaps, explains why we make such a fuss and ritual over personal and home cleanliness but happily dump garbage outside the house, spit and hawk with abandon and deface public property with glee.

Indians are a paradoxical people. We may have no concept of other people's personal space in certain matters, treating the world as our home, but when it comes to cleanliness, there are several degrees of intimacies with space and a rather large degree of selfishness. Note that even within the home the degree of sacredness of a space decides its upkeep.

It isn't as if we don't know how to preserve public space, says Visvanathan. We maintain sacred groves, but choose to neglect public parks. It is all about how we choose to project a space, if it's sacred or has some association of ownership, even community ownership, with us, we respect it. But civic space we regard as sarkari property. And because the sarkar fails us in so many ways, we don't just disrespect its space, we actually take perverse pleasure in defiling, defacing and destroying it.

CRAZY ABOUT CRICKET

An NRI woman from the US who recently came to Delhi said, “I notice Indian males of all ages raising their arms, volleying imaginary balls at an imaginary player as they are walking down the corridor. Or they wield imaginary bats and hit imaginary sixes, making 'tok' sounds with their tongues. Occasionally, you hear them mumble 'shot' or 'out' during this imaginary play, even when their thoughts are partially occupied somewhere else.”

We in India may not even have noticed this behaviour, because cricket is so intrinsic to our lives. “Cricket is an Indian game accidentally invented by the English,” author Ashis Nandy once said.

Indeed, cricket has all the elements of the Indian psyche. It's karmic, starting from the toss that decides who bats or bowls. The pace is slow. In typically Indian style, one man bowls while ten others sit and watch idly. There are mini breaks after an over. A batsman can get out by being clean bowled, run out to several other ways. So many extraneous factors decide the way the game progresses―the weather, pitch, the way the ball frays. And, halfway into the game, you have no idea which side is the winner. In fact, a match can be won in different ways, from scoring more runs to getting the opposite team all out. “Cricket is radial, like Indian philosophy,” says Shetty. Also, cricket is adaptable. It can stretch on for days or be done in 20 overs. It's as comfortable in the gully as it is among gentlemen clad in cabled knitwear.

It is any surprise that the god of cricket wore the Indian blue?

HAGGLING WITH A PASSION

Rs500, says the vendor. What, I could have bought three for this price, you say, and then quote Rs200. He rolls up his eyes in horror, but says, only for you, he will come down to Rs450. Rs250 and not a paisa more, you affirm. He isn't willing to budge. You pretend to walk away, but he calls you back. You settle midway at Rs300 and the deal is struck. You have got your money's worth, he has still made a little profit.

Whether buying or selling, we Indians love to bargain. We could be buying a penthouse on the 33rd floor, or just three dozen oranges from the handcart, but unless we go through the entire ritual of calling each other cheaters, invoking a handful of gods and haggling loudly, the business is seldom concluded to satisfaction.

So, why do we so love to bargain? It makes us feel smart, says author and marketing guru Suhel Seth. “There's a great distrust in us when it comes to trading, we are always looking over our shoulders, wondering if we are being taken for a ride,” he says. “Bargaining is that exercise which makes us feel we have been able to maximise profits.”

The merchant in India, like the one in Venice, is not a popular character. He is traditionally portrayed as the one who makes his profits fleecing the innocent, says Prahlad Kakkar. So, it gives us a kick to feel we have got the better of him, even if that 'trader' happens to be just a hapless hawker.

But there is more that spurs us to haggle. It is the serotonins of satisfaction which course through our veins after a successfully concluded bout of bargaining―never mind whether the purchase was useful or not. Ever get this satisfaction at a fixed price store? Not unless there is a sale on and you clinch a neat 70 per cent discount.

OLD ISN'T GOLD

Mumbai’s Flora Fountain is an exquisite work in Portland stone. But some years ago, when the stone began discolouring because of age and pollution, the enthusiastic civic department gave it a fond lick of oil paint. Conservations were stunned at the slow murder of the stone but civic officials couldn’t comprehend why their efforts were so unwelcome. Was the ageing fountain a better picture than this gleaming one, they wondered, very hurt.

Then there is the story of a stained glass window being broken to install the ducting for an air conditioner unit in a heritage building occupied by a government department. Clearly, when it comes to preserving heritage, Indian attitude is appalling.

So why is it that the English spend a fortune renovating a century-old adobe, while we would rather pull down the ancestral haveli (mansion) and build something in the latest style and materials? Only those who cannot afford the makeover will stay with something old. Note that traditionally, even the family gold was reset in a new pattern for the new bride and she would never think of wearing her mother's sari to tie the knot in.

Old, for us Indians, has a different connotation than in the west. For them, old is a status symbol; here, an embarrassing reminder of poverty. Gleam, sparkle and shine, that is rich for us. A crumbling monument has little to redeem itself, the least that you can do to attract tourists is to whitewash the inside walls, never mind if this means that we have covered the exquisite paintwork of a previous era. It was faded and old-fashioned anyway, wasn't it? Conservation is a new word here, barely comprehended by the masses, and revivalism is still confined to fashion shows.

Till these concepts gain mass appeal, the mantra is: If it looks old, paint it.

INNOVATIVE FIXERS

When the Indian Space Research Organsiation dreamt of going to Mars, it didn't have the first thing required for the journey―a vehicle powerful enough. That was hardly a setback to the dream though. They had their good-old PSLV, veteran of several voyages. With a bit of jugaad, they could send the orbiter riding atop this vehicle, never mind that in the world of space-bikes, the PSLV was only a scooter. Were Isro to wait to get the right vehicle first, the mission could well have been delayed by several years.

That the world sat back and clapped as India broke several global records with its debut on the Martian sphere went on to prove that jugaad isn't necessarily a roughly patched-up job, but an elevated art form that requires a whole set of skills―from a keen eye that picks out the versatility of everyday items to an imagination that can dream up impossible uses of the item and technological acumen that can make these dreams turn true.

“It requires no great introspection to understand that jugaad is the outcome of never having enough of anything around,” says Kishie Singh. “Remember the time when you imported a mixer and it broke down, you would have a problem sourcing spare parts. So you took a bit of twine, cannibalised a defunct machine for a washer and got the appliance back in working condition.” Call it reverse engineering, deconstruction or just a quick fix, the ends justified the means. “We aren't great inventors, but good innovators,” he says.

We see so much jugaad around us that we have ceased to marvel at the Indian genius. A software engineer was getting a bit tired of his mother's grumbling about the smoke building up in her poorly ventilated kitchen. Breaking down a wall to install a proper exhaust fan would take effort and money. So he pulled out the tiny fan from a discarded computer, taped some electric cables to it and installed it in the tiny kitchen window. All in a weekend's work, and at no expense at all.

A doting wife remembers how her husband tinkered with the air conditioning of their brand new car 20 years ago and, through some home-assembled system of ducts and fins, installed a system to bring ventilation to the back seats, too. “Today, you see cars with separate vents to cool the back seats, he did it back then. Our jugaad is often ahead of its times, it's trailblazing,” she says.

Jugaad may have been the solution to a necessity but it thrives in India because it is in sync with the other Indian mindset of recycling. “Only in India does a banian (vest) have a karmic life, going on from undergarment to duster to mop,” says Suhel Seth. Also, in a largely uneducated country where people are not constrained by formal laws of science, they think up possibilities others wouldn't. It also helps that there's little regard for finer points like copyrights and patents in this part of the world.

Unfortunately, by its very definition, jugaad remains a spot solution for a particular situation and is rarely scaled up or patented. Elsewhere, our jugaad experts would have got prizes for their out of the box thinking. Here, at best, they are told, 滴e is of some use, after all.