The Narendra Modi government has kept its election promise to take good care of the soldier—serving and retired. Veterans are getting pension as per their rank, while those in service can look forward to handsome retirement packages and comfortable pensions. The seventh pay commission has recommended hefty hikes in the soldier’s salary and perks, and the government is expected to accept and implement the proposals.

These would entail a higher defence spend. The defence budget has shot up from last year's Rs 3 lakh crore to Rs 3.41 lakh crore in 2016-17. Last year itself, the government spent more than what was initially allocated for military pensions. Though just Rs 54,500 crore was set aside for pensions in the 2015-16 budget, the revised outgo was Rs 60,238 crore. This is going up steeply to Rs 82,332 crore in 2016-17, “due to increase in the number of pensioners and anticipated provisions of dearness relief, implementation of the recommendations of seventh Central pay commission and implementation of one rank, one pension,” explain the budget papers.

The salary bill of the serving soldier is also up. If the government spent Rs 59,303 crore last year on pay and perks to the Army alone, the outgo will be Rs 67,722 crore this year. Navy personnel were paid Rs 4,385 crore last year; this year, they will get Rs 5,273 crore; the Air Force salary bill is going up from Rs 10,236 crore to Rs 12,073 crore. “The salary and pension funds will grow further as the armed forces are looking to expand their size in terms of manpower,” said defence budget expert Deb Mohanty.

No one is complaining. With the economy growing at 7 per cent, money should not be a problem. Cost does not matter, as long as the soldier is happy. He is.

Now, comes the irony. While the soldier is happy, the military is unhappy.

For, the well-paid soldier is ill-equipped. He will have to fight his well-equipped enemy using 35-year-old guns; he will have to fly 40-year-old MiG-21s to take on most modern fighter-jets; he has hardly any helicopters to fly out to look for enemy submarines, and his own submarines are creaking 30-year-olds. If he had hoped that this year he would get a few new weapons, the budget has poured cold water on the hopes. Said B.C. Khanduri, retired major general and chairman of Parliament’s standing committee on defence, which is currently examining the defence budget: “When the government is giving and raising money for one account (hiking pensions under OROP), there will be cuts in other areas.”

The expectation at the turn of the millennium—when the Vajpayee regime conducted nuclear tests, defeated Pakistan in Kargil, said India was shining—was that India would catch the RMA, or revolution in military affairs, in the 2007-2017 decade, when it would spend about $100 billion to modernise its squadrons, fleets and regiments, and bring its military technologically (though not in numbers) at par with China’s, leaving Pakistan far behind. With the Manmohan Singh government opening the military sector to foreign companies in 2005, the process began with a bang. To indicate that business would be big, the government announced that India would buy and make 126 multirole fighter planes and six conventional submarines—each of which came to be known as the ‘mother of all deals’.

But, in its penchant to be politically correct, the UPA government ordered probes into every charge of corruption and blacklisted suspect vendors. The blacklisting went to such an extent that, at one stage, every gunmaker in the world market stood banned. And then, with the slowdown in the economy by 2013-14, the budget, too, came under strain, with a meagre 5 per cent hike for new purchases. In the next fiscal, 2014-15, finance minister P. Chidambaram gave a parting kick—he cut the allocation for new purchases by Rs 13,000 crore.

Narendra Modi came to power, promising a stronger India with a 56-inch chest. Having accused the UPA and its overcautious defence minister A.K. Antony of having neglected the military for ten years, the Modi regime was expected to take quick decisions on buying or making military equipment. One of Modi’s first public speeches as prime minister was to exhort the defence sector to make and export military ware. Then, when the Make in India programme was unveiled, the defence sector was given primacy.

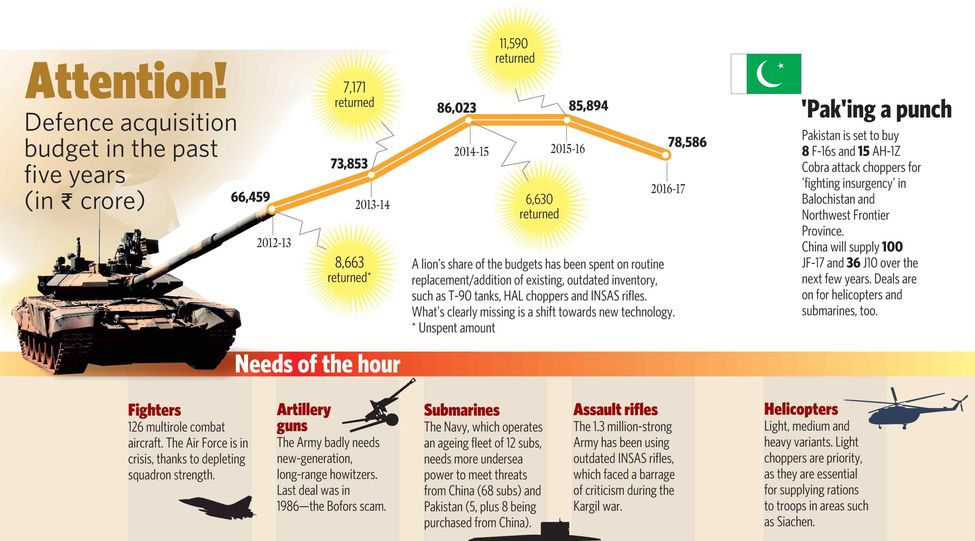

Military minds were overjoyed when the new finance minister, Arun Jaitley, allocated Rs 85,894 crore in 2015-16 for buying heavy equipment (called capital equipment). But then, with major deals failing to fructify, they returned Rs 11,590 crore unspent. Thus, the revised estimates of last year were Rs 74,304 crore.

The defence services’ longterm perspective plan is based on an assumption that the government would give them money equivalent to 3 per cent of GDP, which is considered the ideal limit for a modernising force. But the highest that India ever reached was when it spent 2.41 per cent in the post-Kargil 1999-2000. “There has been a downslide since then,” pointed out retired lieutenant general Prakash Katoch, “not to talk of the thousands of crores of rupees that were surrendered by MoD annually barring an odd year.”

This year, when it was thought that the deals for Rafale fighters, howitzers, self-propelled guns, midair refuelling aircraft and a new line of submarines would fructify, Jaitley has given a meagre 4 per cent hike (Rs 74,300 to Rs 78,586 crore) to the capital budget. Said Gen V.P. Malik, former Army chief: “As a ratio of projected GDP for 2016-17, the defence expenditure will be around 1.6 per cent. In comparison, China spends over 2.5 per cent, and Pakistan around 3.5 per cent of their GDP.”

When calculated against the budget allocation last year, there has been a real cut in the money given for buying new weaponry—from Rs 85,894 crore to Rs 78,586 crore. “Of the allocated amount, more than 80 per cent funds would be required to pay for the deals which have already been signed, and probably Rs 5,000 to 6,000 crore would be available for new acquisitions,” said Mohanty.

Indeed, Jaitley has rationalised the demands for grants and clubbed several of them to avoid accounting clutter, but observers have begun to think that the Modi regime is losing its political interest in defence. “In his very first budget speech on July 10, 2014, the finance minister had talked about many things: one rank, one pension, war memorial, defence technology fund, foreign direct investment, and development of rail network in the border areas, apart from promising urgent steps to streamline the procurement process,” pointed out Amit Cowshish of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, two days after the budget was presented. “The momentum was somewhat lost in the last year’s budget speech as he made just a cryptic reference to the push being given to ‘Make in India’ in defence. This year, however, there has been no mention at all of the defence allocation in his budget speech.” Added Gen Malik: “I can’t remember that happening in the last five decades or more.”

Lack of funds is forcing the ministry to cancel several projects and even withdraw already floated tenders, including a critical Rs 1,500-crore project for arming the Rudra helicopters for the Army, and a Rs 4,000-crore project for buying six ocean surveillance aircraft for the Navy.

The Air Force had been asking for a multirole combat fleet since the early 1990s, when it realised that its MiGs needed to be phased out. Then came the Kargil war, in which the Air Force concluded that it could fight in the mountains only with aircraft like the Mirage-2000, which are armed with high-precision, laser-guided bombs. The demand acquired an urgency and the government okayed a long-pending demand for 126 multirole fighters.

By 2005, India had received offers from half a dozen vendors: F-15s and F-16s from the US, MiG-35 from Russia, Rafale from France, Eurofighter from the European consortium and Gripen from Sweden. After several trials, the Air Force zeroed in on Rafale in 2012, causing heartburn among the Russians, the Americans and the British. So much so that the American ambassador resigned and left, and the British cut development aid.

Graphics: N.V. Jose

Graphics: N.V. Jose

But soon, it was back to square one. Prolonged technical and price negotiations followed, and finally the UPA government left it to its successor to finalise the deal. With the costs going high, and the buyer and the seller disagreeing on technology transfer, business offsets and a score of other issues, the new Modi government, too, could not strike a deal. The government explained that it was haggling hard for lower prices, technology transfer and 30 per cent return business (called offsets) from France. Finally, on the eve of a visit to France, Modi sought to cut the Gordian knot by asking the Air Force to buy 36 planes off-the-shelf, and leave the remaining 90 to be negotiated later.

A year later, even that limited deal for 36 fighters is hanging fire, with India demanding a 25 per cent discount on the offer price of nine billion euros, and the French countering that they can’t sell the plane cheaper than the price at which they sold it to the French air force.

This year’s budget offers no hope. If the spend on aircraft and aero-engines for the Air Force was Rs 18,392 crore last year, it has been cut to Rs 17,833 crore in the current budget. Ministry sources told THE WEEK that the limited Rafale deal may go through this year, but that hardly meets the huge shortfall in squadron strength and technological capability. The frustration came to the fore when Air Marshal B.S. Dhanoa, the present vice chief who is slated to be the next chief, openly admitted that without adequate squadrons, his force was not in a position to fight a war on both the China and Pakistan fronts (as revealed by THE WEEK in February 2015).

Planning decades ahead, the air staff had proposed that by the end of this decade, India would have to start inducting a fleet of futuristic fifth-generation fighters, in addition to the multirole fighters. A Russian design was approved to be jointly developed and manufactured. This deal now looks completely forgotten, with the two countries making no progress over the price for a decade!

Last heard, the government is asking the Air Force to forget the futuristic fighters, and instead build a force of long-range conventional missiles which can strike deep inside China. The air staff aren’t happy. “Missiles have their role, and aircraft have their role,” said an air officer in the planning staff.

Artillery and armour are the cutting edge of any army. Thanks to the arrival of the Russian T-90s in the late 1990s and early 2000s, tank regiments are now well equipped, and purchases of newer pieces from the tank factory at Avadi in Tamil Nadu are steadily going on. The budget, too, reflects this. The Army’s spend on heavy vehicles is going up steeply from last year’s Rs 1,901 crore to Rs 3,412 crore.

But the Army has not got a single new brand of gun since the Bofors scam of the 1980s led to a freeze on gun buying. (The political fear of a scam has been such that even the licence given by Bofors, against payment already made by India, to make the same guns here was not used for several years.) Defence ministers George Fernandes and A.K. Antony tried to break the purchase jinx, released tenders five times, and even tried government-to-government contract, but in vain.

There is good news, now. Three gun-acquisition programmes are nearing completion. The local biggie L&T is making self-propelled howitzers called Vajra, in a tie-up with a South Korean company. A few M-777 ultralight howitzers are being bought from the US. And the old licence given by Bofors is finally being used for making Dhanush guns by Ordnance Factory in Jabalpur in Madhya Pradesh.

The budget reflects the planned inductions. The Army’s spend on ‘other equipment’ has shot up from last year’s Rs 13,863 crore to Rs 16,173 crore this year.

Another Achilles heel for the Army has been its poor run with the locally developed INSAS rifles. Rifles and carbines are needed in millions. The infantrymen are reportedly unhappy with the rifle, and have been asking for a more advanced weapon than terrorists’ favourite AK-47. The Defence Research and Development Organisation is now pushing its close-quarter carbine for trials, hoping that it would save foreign exchange.

On the water front, while the surface squadrons are fighting fairly fit, the underwater scene is breathtakingly scary. After the loss of INS Sindhurakshak and another mishap last year, the submarine fleet is left with just 12 Kilo and HDW submarines, most of them more than two decades old and on their last fins. Half the fleet is out of service at any given time.

Back in the 1990s, the Navy had made plans for acquiring 24 submarines in a 30-year period starting 1999. After 17 years, it has not got even a single new boat. Six Scorpene subs were to be built under a contract with the French, but the programme is running behind schedule. The plan to order six more subs under Project 75 has been hanging fire for five years, with committee after committee looking into the requirement.

With deals failing to fructify, the Navy could spend only Rs 10,681 crore of the Rs 16,050 crore allocated for fleet upgrade last year. This year offers little hope—marginal rise to Rs 12,467 crore, far short of what was allocated in last year's budget.

The situation is comfortable ‘on the surface’: the Navy is sailing more than 140 warships. But hardly any of them can ‘take to air’. Every ship is mandated to have a multirole helicopter on board, which can fly out to look for enemy ships and submarines, rescue fishermen, ferry casualty and so on. But the Navy’s fleet of Sea Kings, which were bought in the 1980s, have mostly been mothballed to save the precious spares from wear and tear!

The force badly needs around 140 choppers for the warships, but has not got a single one in two decades. A tender to buy 16 choppers has been going on since 2009, but the chosen company, the US-based Sikorsky, is demanding too high a price. And this year, the budget for the Navy's air fleet has been slashed to Rs 3,805 crore from last year’s Rs 4,100 crore.

The blame for the delays is as much on the services as on the political leadership and the bureaucracy. Despite being asked to cut down on running (revenue) expenditure, the services continue to ask for more posts, jobs and tasks. (They have now asked for an officer of Army commander’s rank to head the new defence university.)

This has forced Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar to warn them to “cut the flab”, and make use of technology for training. “Several of the services’ proposals to raise new commands, such as the cyber, space and special forces commands, have been put on hold, and forces have been asked to rationalise their requirements in terms of new formations,” said a ministry official.

Both sides—the ministry and the services—are said to have had heated testimonies before the parliamentary standing committee, which is currently meeting to discuss the defence demands for grants. While the forces blamed bureaucrats for the lack of equipment, including even critical ammunition (which comes under the ‘stores’ category in the budget, and not capital) for war-fighting, the ministry officials said forces were delaying every acquisition project, resulting in cost escalation.

Parrikar, caught between the two, is putting up a brave face, suggesting that there is adequate funds for meeting the defence requirements, including for the raising of a mountain strike corps along the China border. The vendors, too, haven’t lost hope, as they had in the 1990s, when most of them turned their backs on India. “India is still an attractive market,” said Gurnad S. Sodhi, managing director of the German defence major ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems. “We are undertaking several programmes here and want to do business here.”

Good luck!