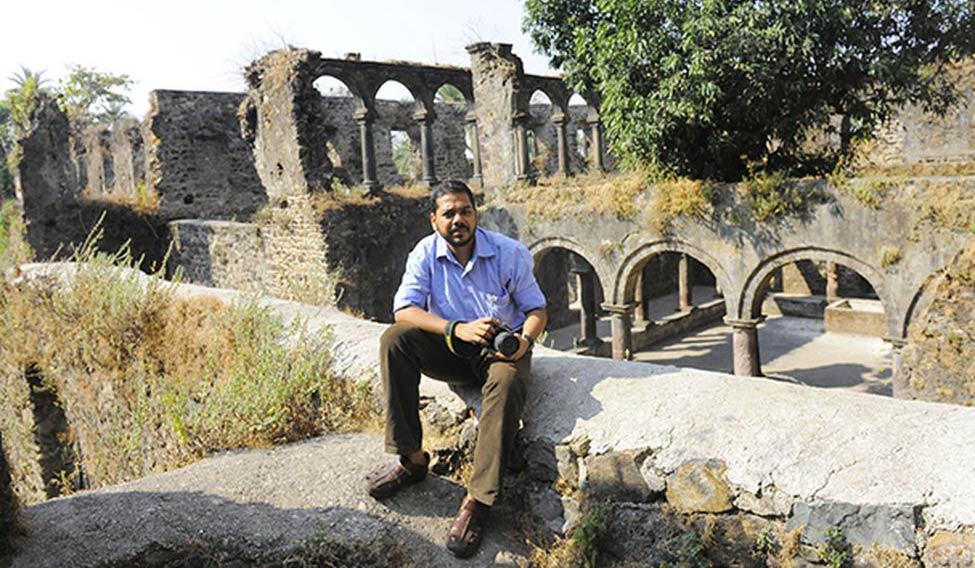

Every day, THE WEEK’s Senior Photographer Amey Mansabdar commutes from his home in Vasai to his office in south Mumbai, about 50km away. As a person who grew up in Vasai, he knows all the landmarks in the area. One of them is only a few kilometres from Vasai Road railway station, where he boards the train to Mumbai―the famous Portuguese base of Bassein Fort.

In 1583, long before it became part of the bustling Greater Mumbai, Vasai (or Bassein, as the Portuguese called it) was home to trading communities that dealt in spices, corn and other agricultural commodities. The vibrant trade culture is what attracted English merchant Ralph Fitch to the place. His account of the journey gave his colleagues back home glimpses of a faraway, exotic land.

He is among the earliest, and least known, travellers to write about Mumbai. That is perhaps because Fitch himself did not publicise his writing. He was a starry-eyed visitor to the Mughal empire and Portuguese trading ports like Vasai. Brimming with curiosity, he described in detail the value of palm trees that dotted the Mumbai coastline. According to him, they were “the profitablest tree in the worlde”, which bore fruit and yielded oil, sugar, vinegar, coir and, most excitingly, wine (toddy, perhaps).

Fitch made several errors in his journal: Muslims were Moors to him and Hindus were “gentiles”! He barely conceals his jealousy for the well-built forts in Vasai, Thane and other Portuguese-dominated areas. He goes to great lengths to describe the wealth of Mughal India, something that triggered widespread interest about India among British traders at that time. The interest snowballed, and by the turn of the nineteenth century, India was firmly in the hands of the British.

Today, a lot of things have changed in Mumbai and its suburbs, but a lot remains the same. Portuguese forts and the toddy-yielding palm trees still dot the coast. The biggest change is certainly the local trains that carry millions of commuters like Amey to their offices in Mumbai.

According to Aroon Tikekar, historian and former director of Asiatic Society in Mumbai, the soul of the city has remained the same over the centuries. “Mumbai has welcomed outsiders, who poured in for centuries; and thanks to this spirit, it is easy to see continuity between Mumbai’s earlier existence as a Portguese trading port and its present megalopolis form,” he says.

The Fort area, which was a key part of Portuguese Bombay, is now a posh address in Mumbai. The Mumbai Fitch saw was dominated by Islam, the religion of the Mughal emperors. With hundreds of mosques in Mumbai, Islam continues to thrive in the city, and so do Parsis and Brahmins.

In the place of toddy, which had many takers in the palm-rich coastal Maratha and Konkan region, 21st century Mumbai boasts affordable bars selling foreign liquor. The strip of bars that stretch from Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (formerly Victoria Terminus) to Fort is frequented by patrons who want to ‘fortify’ themselves for the train ride back home.

With its stunning array of heritage buildings, Fort can easily be a time machine. Near the brilliant, white-columned Asiatic Society building―which is part of the network spawned by Sir William Jones across Calcutta, Colombo, and Bombay―is the remains of a medieval Portuguese structure now part of the defence establishment. But the construction boom and the mad scramble for real estate have altered the identity and the skyline of the area.

Illustration: Bhaskaran

Illustration: Bhaskaran

Historian Dinyar Patel says that the story of Mumbai is synonymous with the search for new land. This quest is what is common between European traders like Fitch and the 21st century real estate developers, who want to “go vertical” to increase the limited space in the city.

Despite its welcoming nature, Mumbai is a city shaped by fear, insecurities, and prejudice, says Patel. Amey was about to board the train to Vasai when shooting started near Leopold Cafe, unfurling the 26/11 terror attacks. Ordeals like that, he says, have made the people of Mumbai soldiers in their own right.

Patel says 26/11 is not the only violent event that left its mark on the city. The communal riots of 1992 and 1993, and the rise of the Shiv Sena have left their own imprints.

According to Patel, Mumbai’s reputation as a welcoming city took a beating in the 20th century. He says the recent efforts to paint Mumbai in a culturally monochromatic hue does not fit its long, multi-coloured background. The Jews, Parsis, Armenians, Christians and other minorities who contributed to Mumbai’s history and culture did not arrive on India’s shores just because they were oppressed back home. “In fact, in most cases, the trading communities chose to come to Mumbai because of its growing reputation as a tolerant urban centre and open trading port,” he says.

Since the riots of 1992 and 1993, incidents of denial of homes to Muslims have increased. A new phenomenon is the “totally vegetarian” housing societies that aim to keep out the religious minorities, says Patel.

In spite of the unwelcome change in the Mumbai’s psyche, the young generation is busy making the best of opportunities the city offers. Supriya Sule, leader of the Nationalist Congress Party, the ruling alliance partner in the state, says it is only a matter of time before Mumbai bounces back. “One can easily understand why European traders wrote back glorious tales of the wealth of India,” she says. “Given its potential, coastal Mumbai offers a lot to visitors. That is why despite some setbacks in the past, Mumbai’s infectious energy is globally famous. A right-thinking youngster will be overwhelmed with opportunities in Mumbai. Therefore, there is no reason to be frustrated about some negative developments in the recent past. Mumbai always recovers swiftly.”

FROM thence we passed by Basaim.... and from Basaim to Tana, at both which places is small trade but only of corne and rice. The tenth of Nouember we arriued at Chaul which standeth in the firme land. There be two townes, the one belonging to the Portugales, and the other to the Moores. That of the Portugales is neerest to the sea, and commaundeth the bay, and is walled round about. A little aboue that is the towne of the Moores which is gouerned by a Moore king called Xa-Maluco. Here is great traffike for all sortes of spices and drugges, silke, and cloth of silke, sandales, elephant teeth, and much China worke....

―From the journal of Ralph Fitch, 1585