Long, long ago, our land came to be invaded by a fierce tribe of white Philistines who came from a land far, far away. They were endowed with such great physical strength, such sharp wit and such magical weaponry that neither the blade of steel nor the blast of gunpowder could destroy them.

However, like Samson who had secreted his strength in his long locks, or like a demon in a Vikramaditya fable, who safe-kept his heart in the body of a parrot which was guarded by serpents living in a castle surrounded by a moat infested with crocodiles, the Philistines suffered from one weakness—they could be destroyed by salt. So they banned salt-making in our land, and ruled us with an iron hand.

One day, there came a prophet who told our people that there was salt kept in a Holy Grail buried on a golden shore, where the land ends at the westernmost sea. But then, only a man who had purified his mind and body by constant fasting and praying could undertake the journey through lands infested with demons, and procure the Grail of salt.

Then, there came a David, frail of body and clad in nothing more than a loincloth, offering to undertake the dangerous journey and procure the Grail. The great knights of the land scoffed at him, but he set himself upon the journey of several days. A large band of the people followed him, while their womenfolk spent their days fasting and praying for their safety.

To cut a long story short, he outwitted all the demons on the way, and reached the distant shore where he picked up the Holy Grail of salt, and returned to his land. As soon as he sprinkled the salt on the Philistines, they uttered a loud cry and vanished.

Couldn't the story of Gandhi's Dandi March be mystified thus? It could have been, if it had happened before the Buddha was born. And the story would have perhaps been India's third epic, after the Ramayan and the Mahabharat.

But why say, 'before the Buddha was born', just like Christ's birth is used as the event that divides eras as BC and AD on the Christian calendar? The answer is simple. The Buddha is the oldest personality of India about whose existence and life events there is universal agreement among historians. There is dispute about the dates of Mahavira who preceded him, but most historians agree that the Buddha lived from 544 BC till 461 BC.

Well, for the sake of record, we know also about a king who ruled before the Buddha—Shishunaga, who began his rule in 642 BC. According to S.B. Bhattacherje's Encyclopaedia of Indian Events and Dates, the Shishunagas are "the earliest dynasty [in India] which has a historical base".

In the time-scale of the world's great civilisations, the Buddha's or the Shishunagas' period is not very ancient. The Egyptians know even the dynastic lineage of the pharaohs who ruled them from 3100 BC; so do the Chinese about the lineage of the Xia dynasty which ruled from 2100 to 1600 BC. Historians not only know about the ancient Greek and Persian rulers but have even got graphic accounts of the battles they fought with each other. There are clear and authentic records of the sequence of Alexander's conquests in the 4th century BC, and how the young Macedonian and his illustrious foe Darius looked like. Who can forget the charged-up face of Alexander on his chariot, aiming his lance at his Persian foe, as depicted in that floor mosaic from Pompeii?

But do we know how our hero, Porus, looked like? For that matter, do we know anything of Porus, except what the Greeks have told us? Therein lies the great paradox of the Indian civilisation. It is acknowledged to be one of the world's oldest, but we know precious little, scientifically, about the times more ancient than the Buddha's.

India's history before the Buddha is so intertwined with mythology that it is difficult to prise out the facts from fiction. Was Krishna a historical personality? Many historians believe so, but most of them also believe that there had been several Krishnas, or at least two—a pastoral Krishna whom we find in the Bhagavata Purana, and a Machiavellian schemer whom we see delivering the Gita in the Mahabharat.

Therein lies the second paradox. While ancient Indians excelled in most branches of learning—philosophies, mathematics, medicine, astronomy, architecture, physics, chemistry, sculpture, grammar, dances, music, and even sexology—they completely neglected historiography.

Look at the iconography of ancient India. We depicted gods and goddesses, sculpted full-breasted Yakshis and naked Abhisarikas, and even sculpted 64 styles of copulation, but didn't bother to record our political history, or even images of our kings. We didn't find a place for our kings on our coins, or for our sages in our temples. Despite ancient Indians having excelled in metallurgy, the iconography on their metal coins is shamefully crude. When the Indo-Greek rulers like Demetrius and Menander (Milinda in Indian texts) in Bactria on the Indo-Afghan border were minting coins with their life-like images imprinted on them, our Ajatashatru, Bimbisara, and even Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka, were issuing crude punch-marked coins.

It was only after the advent of the Islamic rulers that Indians began writing history. Islam, by its theology, is against imaging of kings or, for that matter, of any humans. But the iconoclastic sultans left descriptive accounts of their reigns and their battles, which perhaps prompted the first native historian of India, Kalhana of Kashmir, to write his Rajatarangini. And the eclectic Mughals, who exuded a Persian love for the arts, got themselves painted life-like.

Give the European devils—those white Philistines—also their due. There was no scientific study of India's antiquities till Sir Alexander Cunningham walked across this ancient land, much like an itinerant rishi in search of truth and wisdom, recording its antiquities and correlating its place-names with ancient names found in the mythologies. And then came Sir John Marshall, whom we are featuring among the 25 persons who impacted the most on India's history, telling us that our civilisation is 3,000 years older than we thought.

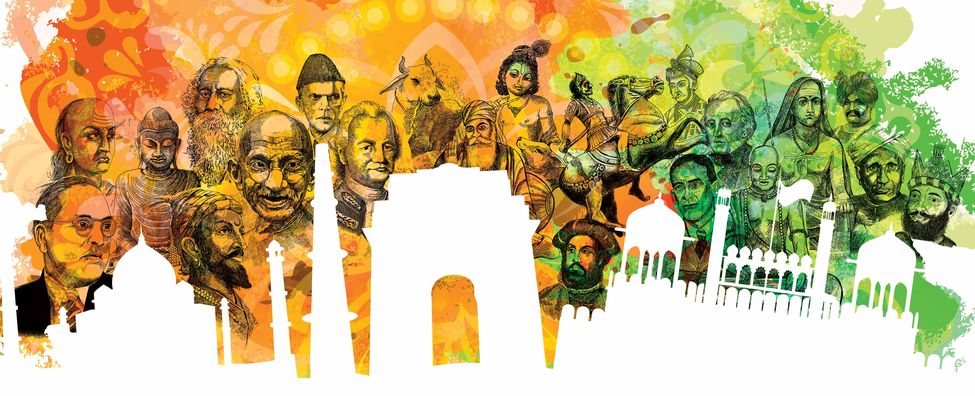

That raises a question about this package of special articles that THE WEEK is offering in this anniversary issue: Why tell history through personalities? The answer is: People make history. And, just as we practise "Journalism with a Human Touch", we also believe in "history with a human touch".

The 25 personages presented here are not necessarily 25 most illustrious men. Among them are great visionaries like Ashoka and Akbar, sages like the Buddha and Shankara, and rapacious invaders like Mahmud of Ghazni and Robert Clive. Indeed, it has been a nightmarish task to select these persons from among other equally competent personalities and, at times, we had to use the editor's fabled blue pencil arbitrarily. But there is one thing common about all those who figure in the list—they are all personages who have had a deep impact on not just the history of their times, but on our times, too, and on the way we live even today, 2,560 years after the Buddha was born.