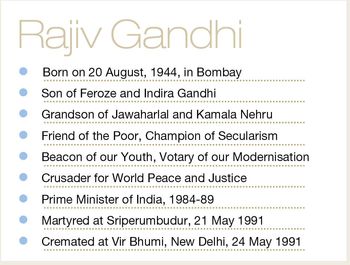

Thirty years have passed since the brutal murder in Sriperumbudur of Rajiv Gandhi. But, in public memory he will always be a young man—he was prime minister at 40 and was killed at 46. In the decade that he was in politics, of which five years were as the prime minister, he achieved much. History will judge and note his many achievements, and his nobility of character and intention. He was a compassionate visionary who was keen to usher India into the 21st century, while sentient of its composite culture and proud of its civilisational past.

With Rajiv, I had the privilege and honour of working on several public projects—the redecorations of prime minister’s secretariat in South Block; the prime minister’s office and cabinet meeting room in Parliament House, Rashtrapati Bhavan, Hyderabad House, Panchsheel Bhawan, Jawahar Bhawan and two official Boeing aircraft. Under his instructions, one also undertook the restoration, conservation and decoration of the mid-19th century Cubbon House, renamed Nehru Nilaya, in Nandi Hills outside Bengaluru. This was developed as the retreat for heads of state who were at the SAARC summit of 1986.

Rajiv had a well-developed, classical and pragmatic approach to design: It must have lasting value, represent our culture and be restrained. He had a very keen eye and was discerning of good craftsmanship. He liked the use of traditional items, in tandem with contemporary sound, light and air-conditioning systems. If modern technology was to be used, it had to be state-of-the-art because he maintained that even the most advanced technologies had a built-in obsolescence. He strongly believed that public buildings were not the property of any individual, but were theirs only to use while they held office. They belonged to the nation and needed to be preserved for future generations.

The most significant work one undertook with him was the restoration and redecoration of the prime minister’s office (PMO) and secretariat in South Block in 1985. He had wanted to restore the “dignity and ordered beauty” of the secretariat as envisioned by Herbert Baker. Together with the aesthetic decoration and furnishing of these rooms, he also wanted all the spaces on the three floors to be rationalised; long-term functional solutions to be resolved for facilities such as sanitary systems, air-conditioning, the miles of loosely hung electrical wirings, and provisions made for all newly-installed computers.

Of particular concern was the upkeep of the stone work, as these secretariat buildings, completed in 1927 and constructed in handsome Dholpur red sandstone, were in a state of deterioration. He was very conscious of conservation and had a great respect for heritage. Rajiv’s brief to me had been precise: “Design an office for the prime minister of India, not for Rajiv Gandhi. My chair must be of the same height as those of my visitors. No elevation.”

He disliked ad hocism and for his approval preferred all plans be drawn up with relevant layouts, elevations and reflected ceiling plans. These approvals were swiftly obtained in the few moments he could spare. Thanks to his background in engineering, he often illustrated design points with quick sectional sketches.

The prime minister’s own chamber was totally redesigned. The room itself is handsome and symmetrically proportioned, but this was lost in the earlier arrangement. All items of furniture were custom-designed for this office. A new desk was manufactured, as the earlier one made in the 1950s for Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru had been shifted to Teen Murti Bhavan. Its replica, used by Indira Gandhi, was now in the prime minister’s Parliament House office. Regarding the soft furnishings, the original and beautiful prison carpet was organically cleaned and re-laid. In the great tradition of Indian textiles, upholstery fabrics were hand-woven and developed in natural fibres. The prime minister also wanted all the artefacts and artwork in the office to represent India’s great culture and artistic skills. Some of the paintings and bronzes, like a superb Somaskanda, were taken on loan from the reserve section of the National Museum and the National Gallery of Modern Art. Other artwork—like Feliks Topolski’s portrait of Pandit Nehru, which hung over the fireplace in the prime minister’s office—were family possessions.

To use as planters, one had collected huge antique bronze vessels mainly from Kumbakonam in Tamil Nadu. An incident comes to mind: After the brutal assassination of Mrs Gandhi, the Special Protection Group was raised to guard the prime minister and his family. They were total professionals who never once acknowledged anyone, even if they had seen the person a hundred times. A few days after one had placed two magnificent antique bronze urulis from Kerala, decorated with floating lotuses, at the foot of the grand staircase of the PMO, an SPG officer seemingly unable to restrain himself asked me: “Ma’am, from where did you get this uruli? It has the name of my village on it!” In the 1980s, vessels such as these were little known in north India. Now their presence is ubiquitous.

In the cabinet meeting room of the secretariat, panelled walls were hung with original watercolour perspectives of Rashtrapati Bhavan and the secretariat buildings, by William Walcot, on official loan from the presidential collection. As one was simultaneously working on the conservation and decoration of the Rashtrapati Bhavan, I had serendipitously come across them in insignificant bedrooms. These presentation perspectives are of great value to architectural historians. The idea was to house them safely, within the four walls of a secure room, to be later displayed in an appropriate institution open to the public.

In the PMO, for years, yards of dust-laden coir matting had covered the corridors to prevent the wear-and-tear of the sandstone flooring. Rajiv instructed that these be removed. All the stone work was cleaned and treated according to expert advice.

The earlier general entrance to the PMO at Gate 3 was converted into an exclusive entrance for the prime minister and eminent visitors. On the eastern face of South Block, “PM’s security demanded the construction of a higher wall. Kohli so followed the pattern of sand stone construction as to stay indistinguishable from the techniques of Baker.” (From the book My Years with Rajiv by Wajahat Habibullah). In the alcoves, on either side of the entrance arch, one had commissioned a master craftsman from Odisha, Raghunath Mohapatra, to sculpt six-feet-high stone diyas based on detailed working drawings that one had provided, as the diyas were in traditional Tamil style. This sthapathi would be conferred the Padma Vibhushan in 2015. I once asked Rajiv if he had any ideas or a brief for this area. He had turned around, almost sharply, and responded, “You are supposed to do the thinking!” That instruction always stayed with me. Designers work best on a one-to-one interaction and he gave me the freedom to conceive.

Also read

- A Kindred Spirit recalls Rajiv Gandhi memories

- Rajiv Gandhi: The caring and cordial democrat

- Rajiv Gandhi opened the doors for 1991 reforms: Montek Singh Ahluwalia

- How Rajiv Gandhi reset India’s relationship with the west: Ravni Thakur

- Politicians of my generation were inspired by Rajiv Gandhi: Bhupesh Baghel

- Rajiv knew a divided Sri Lanka would create problems for India: Mani Shankar Aiyar

- Political naivety overshadowed much of Rajiv Gandhi’s positive work: Rasheed Kidwai

- How Rajiv Gandhi’s peace deals materialised: Vappala Balachandran

If one could refer to him as a client, without sounding disrespectful, then he was an ideal one, because he had an educated approach towards problems and their solutions. He was well-informed, well-travelled and had a wide spectrum of interests—from ham radios to Indian and western classical music, among others. He was enthusiastic and had a keen sense of humour—these were important traits when working under compressed deadlines. That “the PM’s chamber… [has] undergone little change in layout or design despite the succession of nine prime ministers of different parties since then, except for the replacement of mementos personal to the incumbent prime minister, is a testament to Rajiv’s, and Kohli’s success,” wrote Habibullah in his book.

As an epilogue, it is a tragic irony that after Rajiv’s demise one was, along with colleague Romi Chopra, deeply involved in the creation of two national memorials, in memory of a prime minister who had sacrificed his life for this nation—one in Sriperumbudur where he was martyred, and the other in Vir Bhumi in New Delhi, where he was cremated. Shortly after his death, committees were set up, whose ex-officio chairman was always the prime minister. They included many eminent persons and public intellectuals.

The Sriperumbudur memorial was completed and dedicated to the nation by president A.P.J. Abdul Kalam on October 10, 2003, in a deeply emotive and beautiful dedication ceremony conceived by dancer Anita Ratnam. Several reputed architects, artists and sculptors had worked on different aspects of this beautiful memorial.

Rajiv Gandhi Ninaivakam (Sriperumbudur) is essentially a peaceful landscaped memorial designed by the late Prof Mohammed Shaheer. The central spot has a raised platform with a deep red jasper haematite rock marking the place where Rajiv fell. Behind this is a nine feet monolithic granite rock on which is inset, in fine glass mosaic, a portrait of Rajiv. This central spot is surrounded by seven elliptically placed granite columns, designed by K.T. Ravindran. These soaring and massive columns have low relief sculptural carvings of different wave patterns, representing the seven great rivers of India, conceived by the artist A. Ramachandran. They are crowned by symbolic bronze sculptures by Ram V. Sutar.

Each symbol represents the seven virtues and ideals inherent in this “noble and visionary leader. A man of infinite compassion, courage and fortitude [who was] deeply imbued with the spirit of service and sacrifice.” (Sonia Gandhi)

These columns represent the lofty ideals of dharma (faith), satya (truth), nyaya (justice), gyan (a quest for knowledge), tyag (supreme sacrifice), shanthi (tranquillity) and samriddhi (abundance). These collectively represent good governance. Into the foundations of these columns had been “added the sacred soil from those places across India where brave men and women (had) laid down their lives for our beloved nation… sanctified by the life-giving waters from the sacred rivers of India.” (From the Rajiv Gandhi Ninaivakam monograph). Behind the sacred columns one sees a 40-feet-tall curved bas relief in carved granite blocks which starts from the Descent of the Ganga and depicts the ‘Spirit of India’. This was conceived by Ramachandran and was sculpted by 80 sthapathis from Tamil Nadu.

Frequently, while working on these memorials with several colleagues, one silently wondered whether Rajiv would have approved. His absent presence was often palpable.

Every time one reads the inscription below, on the granite plaques, placed at the entrances of these memorials, one is still deeply moved.

Sunita Kohli is an interior designer and conservator, author and occasional essayist.