The good news is: there is food for all, enough and more. Our godowns can beat several months of lockdown.

Together, 140 crore Indians eat 214 lakh tonnes of grain a year—as rotis, rice, biscuits, noodles, poha, idlis or whatever—and our warehouses have 565 lakh tonnes. If together 140 crore Indians can prevent the coronavirus from reaching our paddies and fields through community transmission, our farmers can safely walk to their fields to harvest a bumper this season which, by early estimates, should yield about 2.9 crore tonnes.

Not just roti and rice, there will be dal, too. Pulses are in plenty. The season is yielding 2.3 crore tonnes, which is 27.6 lakh tonnes more than in any year since 2015. And, oil to cook these. Oilseeds production is estimated to be 26.7 lakh tonnes more this year, and sugar 40.7 lakh tonnes more. So with most other food.

The challenge is how to get this food from the godowns to the locked-down markets. A few lakh among the 140 crore will have to venture out, taking the risk of being bitten by the virus, and move this grain from the godowns into our kitchens—loaders, drivers, managers, mandi merchants, book-keepers, grocers and shop boys. To keep them going, and to keep the rest of the 140 crore Indians staying home alive, there will have to be power distributors, telecom engineers and water suppliers. To ensure that the sick among them are treated, there will have to be nurses, doctors, paramedics and hospital managers. And to ensure that all these are running well, there will be another few lakh of the constabulary, bank clerks and pay cheque writers, all of whom will have to stay alive and be healthy. Even during a three-week lockdown, several millions will have to venture out, risking infection.

Soumen Joardar, able-bodied in his 30s, is willing to lend a hand. He had lost his cook’s job in an eatery in coronavirus-shut Kerala and travelled home in Nadia, West Bengal, hoping to land a farmhand’s or a coolie’s job. But the police have locked him up at home, for fear of him having contracted the disease in the train that was carrying unknown hundreds, none of whom was checked when they reached Howrah.

West Bengal’s and India’s clear and present worry is: if Joardar is carrying the virus, he could infect the vast paddies of Bengal, and could start the most dreaded phase of the pandemic—a community outbreak that could land lakhs in sick beds, and kill a few thousands.

JOARDAR’S worry is different: how will he and his family eat, if he sits at home with no work and no pay? This is essentially what the group of ministers and a 30-member team of joint secretaries have been trying to address since early February, soon after three students who had flown in from Wuhan were reported to have Covid-19.

The early steps had floundered. When the group met first on February 3, there was no one from any of the economic ministries. The only step they could take was to ban travel to China and quarantine those who had arrived from China. The government could move only after the festivities around the visit of US President Donald Trump ended. As cases multiplied, the prime minister’s principal secretary P.K. Mishra reviewed the situation with National Security Adviser Ajit Doval, principal adviser P.K. Sinha, cabinet secretary Rajiv Gauba, and Chief of Defence Staff General Bipin Rawat. A group of ministers, too, was set up including Health Minister Dr Harsh Vardhan, Civil Aviation Minister Hardeep S. Puri, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar and Minister of State for Home G. Kishan Reddy to work out policy guidelines.

On March 4, an inter-ministerial meeting asked states to impose travel restrictions, monitor airports and earmark hospitals dedicated for Covid-19 cases. “We have been in alert mode since March 4, when the case of an infected Italian tourist came before us,” said Rajasthan Health Minister Raghu Sharma. “We have undertaken contact tracing for all the cases that have been reported in Rajasthan.”

By March 10, the Centre was in full combat gear, though by then red alerts about the possibility of community spread had been raised by many. Promptly, the government moved to suspend all visas, invoke the Epidemic Diseases Act and the Disaster Management Act. Two days later, Karnataka reported the first Covid-19 death—of a 76-year-old man.

But what after invoking of special laws and issuing guidelines? Few had a clue. The Covid-19 pandemic is only the seventh “biological” disaster notified by the government in 44 years. The first was Ebola virus in 1976, which killed 14,700 people, then the Nipah attack in 1999 that claimed 265 lives, SARS in 2002 that took 780 lives, H1N1 in 2003 (450 lives), H1N1 in 2009 (17,000), and the 2012 MERS (860). Fortunately, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) had, in 2009, issued detailed guidelines on management of biological disasters, as also hospital safety measures in 2016.

Also read

- Indian consumers cautious about spending amid COVID-19 crisis: KPMG

- After US, India has done most COVID-19 tests: White House

- Karnataka minister's wife, daughter test COVID-19 positive

- Man posing as plasma donor arrested for duping Delhi Assembly Speaker

- Kejriwal analogises the fight against COVID to the strife in Ladakh

- Lufthansa offers to fly empty planes to India and carry passengers on outbound flights only

- Google Maps to alert on Covid-19-related travel restrictions

- Covid-19 not 'exploded' in India but risk remains: WHO expert

Yet it was found that most ministries and departments were working in silos. “This approach increased the burden on the health ministry,” admitted a health ministry official. “We found gaps in training the people and society at large on how to respond to a situation like the Covid-19 outbreak. A biological disaster cannot be prevented by medical or clinical interventions alone. The response Covid-19 is demanding is much bigger.” Agreed M. Shashidhar Reddy, former NDMA vice chairman: “In disaster management, the government needs to prepare for the worst-case scenario, where it needs to focus on increasing testing facilities, ensure that the isolation wards do not become breeding grounds for the virus and build resources on a war-footing to provide kits to anyone, irrespective of the fact whether they have travelled to a foreign country or not.”

By now, alarm signals had started ringing. As markets tumbled, and the economic costs became apparent, the Prime Minister’s Office tasked all ministries to prepare for the crisis. On March 19, Prime Minister Narendra Modi set up a task force under Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman.

SITHARAMAN was clear from the beginning that this needs money, and a lot of it. So her first move was to raise revenue. Cellphones were made costlier with goods and services tax hiked from 12 per cent to 18 per cent. The Finance Bill was amended, arming the government to raise special additional duty on petrol and diesel. Another road and infrastructure cess was imposed on petrol and diesel. The simultaneous fall in world crude oil prices was a bonus. There would be more money in the treasury.

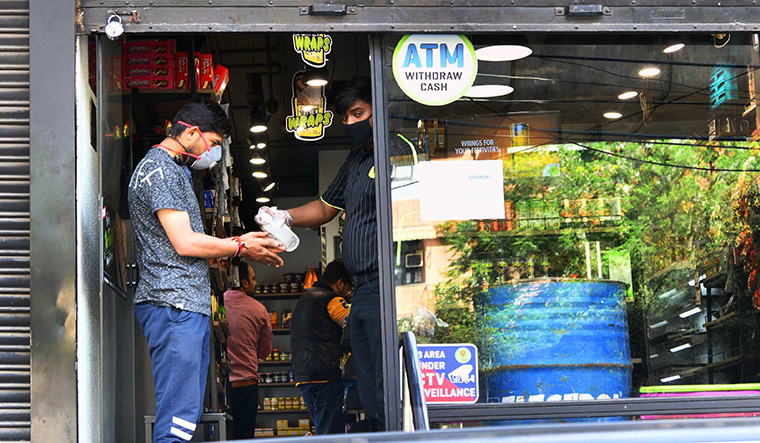

The next task was how to reach this money to Joardar and the millions like him, healthy or sick, who are going to sit at home with no work and no pay. The job of providing immediate relief was left to the states since they are better equipped. Some states like Kerala, Punjab and Delhi had already hiked pensions and offered pay and pension advances while states like Uttar Pradesh put money into the poor man’s Jan Dhan accounts. In tandem, Sitharaman asked the food ministry to let states take three months grain on credit from the Food Corporation of India godowns, asked banks to let the poor draw out their balances, and to make ATM withdrawals free and without limit.

Simultaneously, she also moved to address the larger economy where the money is made. The lockdown would slow down or even halt factories, throwing the economy into a tailspin and also throwing organised workers into penury. Even as Modi announced a 21-day lockdown, Sitharaman pushed income tax and GST deadlines and promised to come out with more. Invest India, the national investment promotion and facilitation agency under the commerce and industry ministry, launched a dedicated platform to address businessmen’s problems.

Yet, millions are still worried. Cabbies, for instance, the ones who have bought their cars on loans. With none riding them, how would they pay the monthly instalment? Would Sitharaman ask the banks to ease the recoveries? For how long? At the other end, the worry is: if recoveries get delayed, would banks collapse? “To help the vulnerable who may lose their livelihoods, the government must make generous cash transfers and provide increased volumes of subsidised grains,” former NITI Aayog vice chairman Arvind Panagariya told THE WEEK. “The target group for this could be urban BPL families under the Food Security Act.”

Finance ministry officers said all the options were on the table—bailout packages for the industry, dole to those who have been thrown out of work, cash to farmers through Pradhan Mantri Kisan Sampada Yojana, tax cuts, interest cuts and easy loans for the corporates, quick building and equipping of hospitals and clinics, easing of rules for the drug and germ-fighting industries. Already Labour Minister Santosh Kumar Gangwar has asked states to transfer money from labour welfare cess collection—a fund of Rs52,000 crore which was rarely used—into the accounts of about 3.5 crore construction workers through direct benefit transfer. Promptly, Punjab and Delhi put Rs3,000 and Rs5,000 in the accounts of every building worker.

But what do the people do with the money if shops are closed and grocery and vegetables do not reach them? Fuel pumps were exempted from the lockdown to ensure the movement of trucks and trains. “We are working to ensure that supplies of essential products to the people are not disrupted,” said Petroleum Minister Dharmendra Pradhan. “At the same time, we are ensuring safety of our team members.”

As flights were grounded and trains stopped for the first time (save for the great Indian railway strike of 1974) in the railways’ century and a half history, the worry was how to move the grain, goods and grocery. “There is an opportunity, too, in this,” pointed out a railway officer. “With no passenger trains running, we can move the goods quicker.” On the day of the start of the lockdown, more than 500 rakes had been loaded with foodgrain, salt, cooking oil, sugar, milk, fruits, vegetables, onion, coal and petroleum products.

As ministerial lethargy gave way to energy, bureaucratic red tapes got cut. As the geniuses of administration took charge of running trains, goods, supplying fuel and moving grain, and as the health warriors waged their own wars in hospitals, other bigger worries were mounting, the biggest being—how to keep more people away from the sick bed?

As most of the clinical management was left to the states, the Centre decided that it should be more in support and facilitation mode than actually curing the sick. A control room was set up in the health ministry where two lakh calls have been answered till the start of the three-week lockdown and 52,000 emails answered. By then 1,87,904 persons, including Joardar, had been kept under surveillance. Another 35,073 had completed the 28-day observation period, and 12,872 samples had been tested. The silver lining in the cloud was that only 52 of them had tested positive for Covid-19.

THAT, however, was no relief. There was still no guarantee that more would not. The biggest task at hand was to keep India germ-free. The grain godowns may be full, but so had to be the chemist’s shelves. There had to be enough and more of germ-killers.

The drug factories had to be kept running, for everything from Crocin to cancer drugs to be available for the sick, as well as for those who could get sick. There were two problems—one, China, the largest supplier of bulk drugs, had cut production. Two, shipping had slowed down, with each ship having to be sanitised before entering ports, and ports banning berthing of ships coming from the coronavirus-hit ports of China and Europe. Reacting to the situation, the Dr Eswara Reddy-led committee that monitors the supply of bulk drugs asked the civil aviation ministry to let them be flown in by cargo planes.

By now, the opposition was carping. Indeed, they had several grouses. The government had not taken them into confidence, and, as Congress leader Ajay Maken alleged, had even ignored the appeals made by Sonia and Rahul Gandhi. They also blamed the regime for having allowed export of raw materials for masks and coveralls at ten times the usual price till March 19. Randeep Surjewala, chairman of the Congress’s communications department, said that the health and textile ministries, between February 1 and March 3, did not even decide specifications for manufacture of these equipment.

By mid-March, the commerce ministry got into the act. It banned export of personal protective equipment kits, masks, sanitisers, ventilators, chloroquine and other medicines that are used to fight Covid-19. “Market requirement of masks has crossed 500 per cent,” said Sandip Chhettri, COO of TradeIndia, an e-commerce marketplace. Added Vikas Bagaria, founder of PeeSafe, a brand that makes toilet seat sanitisers and dust masks: “My employees are working in three shifts.” To ensure that the plants got enough chemicals to make hand sanitisers, the government removed quota limits on ethyl alcohol and extra neutral alcohol. With bars locked down in these ‘unhappy hours’, distillers are pitching in by producing alcohol-based lotions.

Indeed, the scrub-and-clean industry is booming. To be fair, in these times they are not only lending a hand but their hearts, too. Lotion-makers RB India, HUL, ITC, Godrej Consumer, Himalaya and Dabur declared that they would not hike prices. The government, too, moved to tame greedy traders, if any, by capping shop price of 200ml hand lotion bottle at Rs100 and the common man’s mask at Rs10.

But the bigger war on the germ is being waged on the streets, in airports, hospitals, police stations and neighbourhood groups where a hunt has been launched to catch the infected. If the scandalous behaviour of a Kerala family that had returned from Italy and had gone around infecting cousins, aunts, shopkeepers and neighbours put the fear of the virus in the minds of one and all in the state, it was a picture of callousness elsewhere in the early days. For instance, Joardar told THE WEEK that no one had checked him when he got down at Howrah. In Hyderabad, 150 teams of constables, police, health workers and municipal staff are making 2,000-2,500 visits to the city’s nooks and corners to see whether there are any who are hiding their symptoms. Six people have so far been picked up and sent to isolation centres. “Anyone who is not following the order will be sent to the isolation centres, whether they have the Covid-19 symptoms or not,” M. Mahender Reddy, director general of police, Telangana, told THE WEEK.

In fact, it was Modi’s Janata Curfew of March 22, which was a dry run for the longer three-week spell, that revealed that most of India had not yet got the fear of the germ in the right manner. Video clips had gone viral on social media showing netas and aam aadmis having fun in large groups at the 5pm siren, defeating the purpose of voluntary isolation. Delhi was particularly worried, with the city having received 35,000 people from abroad after airport screenings began. The Arvind Kejriwal government promptly asked all district magistrates to ensure that all of the arrivals remained under two-week quarantine at home. The vigil was intensified a day after Janata Curfew. In Punjab, the police arrested 111 persons the next day, and registered 232 FIRs for defying curfew.

The response from the people also has been varying. For instance, the Assam Police find that people are cooperative. “Everyone who has returned from abroad and from corona-intensive areas has been directed to go in for home quarantine. Since March 21, everyone coming into the state is compulsorily home quarantined,” said G.P. Singh, additional director general (law and order) Assam. “The state health department through its field workers, district administration staff, village headmen and the institution of village defence parties is monitoring those who have been hand-stamped for home quarantine.”

There were other worries, too. There were reports of discrimination against certain sections, especially those from the northeast who have physical resemblance to Chinese people. “I discussed this with the home ministry, and they have issued an advisory against discrimination and racial remarks against people from the northeast,” Sports and Youth Affairs Minister Kiren Rijiju told THE WEEK. “There is need for sanitisation and sensitisation.”

POLITICALLY, too, India is now coming together. Most of the opposition parties have welcomed the curfew and other measures and even the Shaheen Bagh protesters have gone home. As Modi invoked mythological allegories to keep his spiritual folk home, the opposition, too, got the message. “Do not breach the lakshman rekha,” he appealed to the citizens.

The relief was that unlike Italy or China, India has locked down before the unknown hundreds in Joardar’s train to Howrah began reporting sick. “We still have not received any evidence to suggest that community infection has started,” said a health ministry official.

But as India went into lockdown with such optimism, the planners and managers became worried. Even if most Indians survive the three-week ordeal hale and hearty, how would the coming months be for the Joardars and their kin? “Most of them, at least 60 per cent, who have come back home in packed trains, would not get back their jobs,” said Prof Abhirup Sarkar, a member of the Technical Advisory Committee. “The rich will survive, middle class might fight back, but the poor will face a horrific situation. Depression would be an understatement. We are heading towards economic disaster.”

That precisely is the worry that is nagging the GoAir pilots who were sacked, the IndiGo crew who were handed pay cuts and Sanjoy Singh, 38, from Bhagalpur, Bihar, who lost his security man’s job in coronavirus-shut Mumbai. Modi has urged businesses not to sack staff and a few have heeded. “Our commitment to not retrench any worker including blue collar and contract workers resonated well with PM Modi,” said Confederation of Indian Industry President Vikram Kirloskar after his video-meeting with Modi along with other honchos. The assurance keeps Singh going. “I will have to search for another job,” he said. “But whatever might happen, I will go back to Mumbai. Mumbai can give jobs to everyone, poor like me and the rich.”

Moreover, corporate bodies have started looking at post-lockdown and post Covid-19 opportunities. A CII report submitted to Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal suggests ways to take advantage of the trade shutdown in China. Suggestions include identifying other countries that can substitute for imports of key products from China, as well as positioning India in other markets as an alternative to China. “With every challenge there comes an opportunity. This can be the turning point for Indian manufacturing if it plays its cards right,” said Ravi Saxena, managing director of Wonderchef, a home appliance company.

But the middle class, especially the small businessmen, are not so hopeful. “Business was grim due to the overall economy slowdown, but the coronavirus scare and lockdown has brought it to its knees,” said Harneet Singh Ajmani, who runs his father’s electronics shop in south Delhi. “Distributors cannot guarantee fresh supplies. Even before the lockdown, supply of goods from China—LED TVs, mobile phones and air-conditioners—had started disappearing from the shelves.”

Economists fear a supply chain cut-off even after the lifting of the lockdown due to lack of production. That would push prices up, plus the government will need to borrow either from the RBI or the markets to defeat the disease. Warned Dipankar Dasgupta, a visiting professor of economics at Ashoka University: “In the entire history of the global economy, we have never faced this kind of situation. It is a major threat for the civilisation. The situation has come to such a pass that if things do not improve, we would have to pay a heavy price.... Markets will be uncontrollable as the people will be staying home and not participating in production activities. This happened because government has not found any medical solution to this pandemic. So they are looking for draconian options like lockdown and subsequent economic options. I am afraid that there is no solution for economists to offer.”

But the clear and present danger is still the fear of the virus. Managing this fear is India’s biggest challenge today that is worrying everyone from Modi to the constables in Nadia who are keeping an eye on Joardar.

With Pratul Sharma, K. Sunil Thomas, Namrata Biji Ahuja, Rabi Banerjee and Soni Mishra