Digital payment services providers were the happiest when Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the demonetisation of high-value notes last November. They hailed the move as a ‘game changer’ that would bring to the fore digital transactions in a country which had the highest cash usage vis-a-vis GDP. With the intention of pulling out cash in circulation as fake currency or as black money, the government promoted the more transparent digital transactions and launched a special programme called ‘Cashless India’ under the umbrella of Digital India programmes.

Five months later, however, the digital drive seems to be going nowhere. Data from the Reserve Bank suggest that people are getting back to their cash-hoarding ways. “We are witnessing a rise in cash transactions in the months post demonetisation,” said Dr Jaimini Bhagwati, RBI chair professor at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations. “This could be because of multiple factors, but what is more worrying is that there is a corresponding drop in digital transactions. This will keep the cost of currency high for India.”

Currently, the country bears about 1.7 per cent of its $1.2 trillion economy as cost of cash. This was set to come down to 1.3 per cent with increased usage of digital transactions, a government committee on digital payments, set up by the finance ministry, said in March.

It is not just the common man, even traders and small businesses have gone back to cash. Many medium and small business owners said the cash crunch was not over and there was a propensity to conserve cash. “Most of the temporary labour in our factories and godowns are paid in cash. We are somehow managing as there is no way without cash,” said Anil Bhardwaj, secretary general, Federation of Indian Small and Medium Enterprises.

He said a majority of the FISME members were unable to go cashless for a number of other reasons as well. “There is a 2 per cent charge levied on cash transfer from mobile wallets. So, with cash available now, traders who were earlier forced to operate on reduced margins, are no longer willing to sacrifice,” he said.

Uma Maheshwaran, a Delhi-based food business entrepreneur, said his suppliers accepted nothing but cash. “My staff says that they need to pay for their daily needs in cash, as small retailers who were earlier accepting Paytm have all stopped using them now,” he said.

The bank charges levied on card payments made at points of sale in retail outlets had a similar problem. It first came up with petrol pump dealers, who went on strike refusing to pay a 0.75 per cent bank charge on card sales. The government responded by waiving the bank charges for consumers alone.

“I had installed card machines of three banks after demonetisation. But retail customers are mostly reluctant to pay 1.5 per cent extra bank charges on their bill. So we are back to cash trading,” said Nikunj Gupta, a hardware trader in Lajpat Nagar, Delhi.

RBI data also suggests the return of the cash economy. In November, a total of 66.4 crore transactions worth Rs 94.04 lakh crore took place on electronic payment systems. It peaked to Rs 104 lakh crore by December and then fell to Rs 97 lakh crore in January. In February, the figure stood at Rs 92.6 lakh crore.

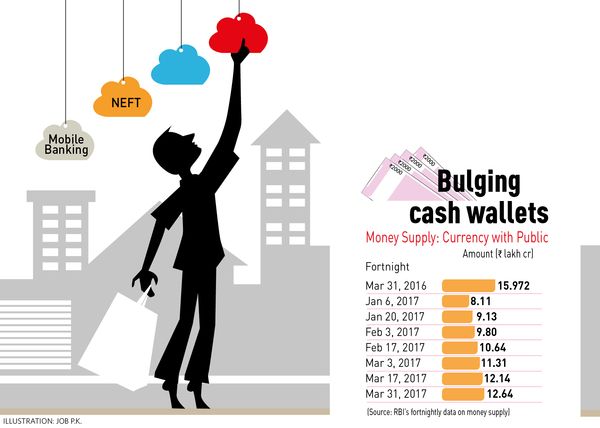

In contrast, the availability of cash, which was registered at 08 lakh crore in January, was half the money supply available in March 2016 (about Rs 15.9 lakh crore). It climbed steadily to Rs 12.6 lakh crore by end March, RBI’s fortnightly data on money supply showed.

In the case of mobile wallets, after registering Rs 1,320 crore in usage value in November, business has picked up and remained stable. It touched Rs 2,100 crore in March, after dropping to Rs 1,870 crore in February. “This is an inflection point for mobile wallet companies, as they would have to now competitively expand the user base. To achieve this, other than the government efforts, initiatives would also have to come from the fintech companies,” said Dharmakirti Joshi, chief economist, CRISIL.

Joshi pointed out that the recent guidelines issued by the RBI for PPIs (prepaid payment instruments), seeking to make KYC norms mandatory for them, may have stemmed the enthusiasm for mobile wallet companies. “We have jointly petitioned to the RBI that mobile wallet customers cannot be treated with the same benchmark meant for bank customers,” said Upasana Taku, co-founder of mobile wallet company Mobikwik. “Our customers keep money with us to meet consumption needs and not savings needs. Once the regulations are clear we are launching a host of innovative initiatives to popularise mobile wallet payments at hospitals, for insurance premiums and other big ticket payments as well.”

But experts said the concerns about mobile wallets remained. “There are two major issues that would have to be first resolved before mobile wallets can grow any further,” said Sushmul Maheshwari, CEO of RNCOS Business Consultancy Services, which conducted a survey on mobile wallets post demonetisation for ASSOCHAM. “One is that many mobile wallet apps compromise security by having access to bank passwords sent over SMS. Second, there is the issue of the suitability of a commission-based revenue model as practiced by wallet companies, which may work with online service providers, but has not really gained as much momentum with offline business owners.”

The expanding user base of mobile wallets, which has grown 20 times in the past three years, has prompted fresh technological needs for these companies. “Many first-time users had a not-so-smooth transaction electronically. The reasons were weak bandwidth, congested server space and bad network for many users,” said Vivek Belgavi, financial technology leader, PricewaterhouseCoopers, India. “Also, weak grievance redressal by mobile wallet companies could have discouraged consumers and small businesses from using them after the cash supply situation improved.” He said a lot of thought is being put into reinventing the business of mobile digital payments as most wallet companies realise that the exponential growth they had projected post demonetisation remained a distant dream.

Some experts also felt that the digital payments platform, which is heavily backed by ICT (Information and Communication Technology), has its challenges in infrastructure. In contrast, the offline digital payment mode of USSD (Unstructured Supplementary Service Data) has really picked up. “USSD volumes have grown almost three times to Rs 35 lakh crore in March. There is a hopeful story here,” said Ritika Mankar, senior economist at Ambit Capital.

There has never been any doubt that cash would make a comeback. “Perhaps no one had realised that it would be so soon,” said Mankar. “The government must realise that making it difficult to avail cash would not necessarily boost digital transactions. In fact, it can potentially suffocate the economy which is still largely informal and contributes more than 70 per cent of the nation’s GDP.”