When Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced demonetisation of high-value notes on November 8, 2016, four government mints—in Noida, Hyderabad, Kolkata and Mumbai—embarked on a mammoth task. They worked into the night for many days to churn out coins, to help the government manage the cash shortage. The government released coins worth around Rs 5,000 crore, mostly in rural and semi-urban areas.

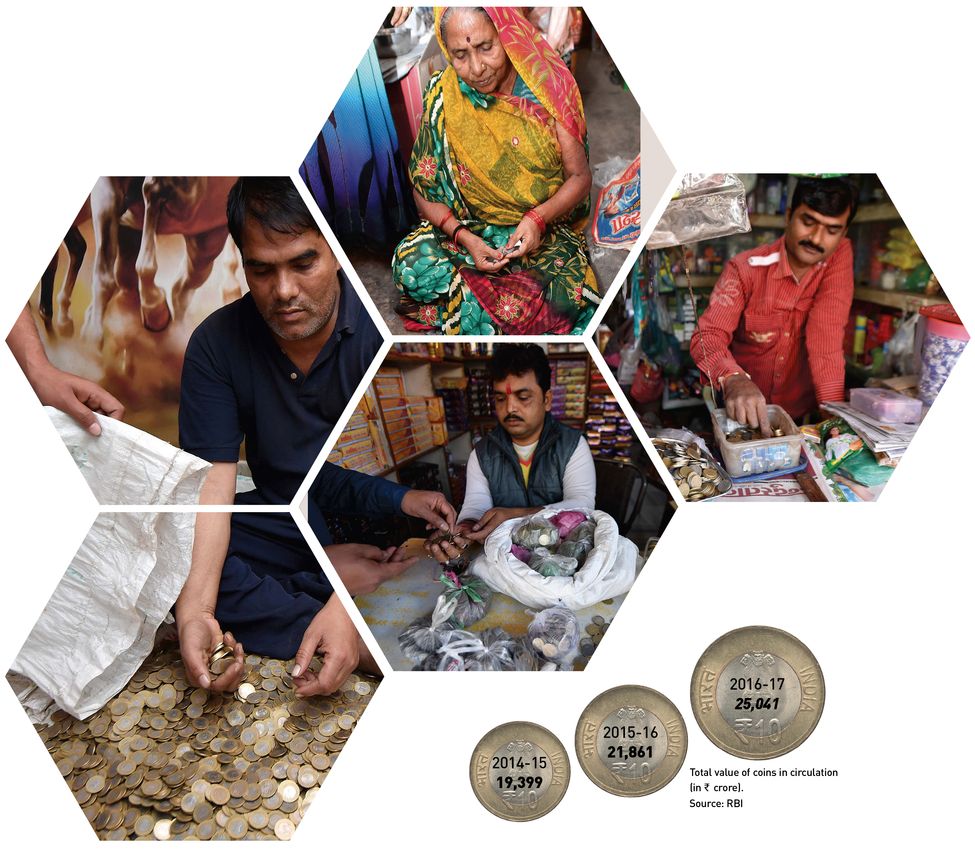

Reserve Bank data shows that the total value of coins in circulation jumped from about Rs 19,300 crore in 2014-15 (a year before demonetisation) to about Rs 25,000 crore in 2016-17. Earlier, coins in circulation grew at a pace of 6-7 per cent a year.

Delhi-based public relations entrepreneur Imtiaz Alam said he was paid Rs 20,000 in ten-rupee coins just after demonetisation. “I needed the money badly for a jazz show in Goa, and the daily withdrawal limit was only Rs 2,000,” said Alam. The sack weighed 16 kilos. “I carried it in an auto-rickshaw,” said Alam.

Though Alam and other Delhiites started getting new currency notes soon, coins continued to pour into smaller towns. And now, banks in these areas, which gave these coins to depositors, are turning away those who want to deposit them. “We pay an 8 to 10 per cent ‘rejki conversion commission’ [an unofficial fee] to currency dealers for converting these coins to notes,” said Ishan Agarwal, owner of Avon Food Products in Kanpur.

Outside his bread factory, trucks wait as usual to pick up their consignments, and among the payments he has collected in the morning is a sack of coins weighing 38.5 kilos. From the weight, he has calculated that the sack contains 050,000. He said his hawkers ware paid in coins by the customers, and the hawkers used the coins to pay the dealers. “The dealer works at a 2-3 per cent margin. So we cannot expect him to pay the coin conversion charges. It is a huge blow to our margins but we are bearing it to stay in business. And, after demonetisation, banks have just stopped accepting coins from us,” he said.

Traders in Kanpur say half the capital of their downline traders in rural areas is stuck in loose change. “The small change received by businesses is getting transferred to transporters. Every transporter is sitting on bags and bags of rejki (loose change),” said Shyam Shukla, state president of Uttar Pradesh Yuva Transporters Association. “The banks won’t accept them and petrol pumps refuse payments in coins. Where can we take them?”

RBI officials in Kanpur said trade bodies and district authorities had approached them with the problem. An official said coins worth around Rs 3 crore were likely to be circulated by the branch shortly.

The Kanpur Electricity Supply Corporation sat on coins worth Rs 25 lakh for months as its bank did not accept them. “We had a contract with our bank. So we insisted on the clause in the contract that obliges our bank to manage our cash and made them accept the coins just recently,” said S.K. Singh, DGM (finance) of KESCO. It has stopped accepting payments in coins from customers.

The RBI had issued a circular twice last year—in March and July—saying banks must accept coin deposits up to Rs 1,000 a day from a depositor. I tried to deposit ten-rupee coins worth Rs 1,000 at the Bai-Ka-Bagh branch of State Bank of India in Allahabad, but was turned away by the teller. The branch manager pretended that he was unaware of the circular, but when I showed him a copy of it, he said it applied only to branches that had a currency chest. The Coinage Act says banks refusing to accept coins can be penalised. RBI officials suggested that depositors should go to the banking ombudsman if banks did not accept coins. “The ombudsman follows a time-bound procedure and banks are penalised monetarily and administratively depending on the quantum of the violation,”said an RBI official.

In Allahabad, sugar agents and small traders are stuck with huge quantities of coins. “Traders here would have Rs 1 lakh each in coins. If we refuse to accept them from customers, they threaten to go to the police,” said Shivbabu Kesarwani, who runs a grocery shop in Gurpur. “We can neither discard nor keep it. The government should do something to rid us of this alakshmi (goddess of misfortune),” said his septuagenarian mother, pointing at a sack of coins on the floor of her house.

Ali Anwar Ansari, former MP from Bihar, raised the issue in the Rajya Sabha last July, citing the difficulty of villagers in Siwan and Munger districts. “I suggested that the government must do a second round of demonetisation, one that can suck out this excess of coins in circulation among the poor and rural citizens and provide them with bank notes instead,” he said.

The RBI had encouraged banks to hold 'coin melas' in areas facing a glut of coins, but it did not have much of an impact. A handful of banks organised coin deposit camps in Agra, Siwan, Mandya, Mysore, Halol, Purulia, New Jalpaiguri, Balasore and Raipur. An ICICI Bank official said banks were not keen on organising such camps because of the handling and logistics hassles. Recently, the RBI again issued advisories to banks, asking them not only to accept coins from depositors by organising coin melas in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal and Karnataka, but also to sensitise depositors about the need for having adequate coins in circulation.

The finance ministry did not respond to THE WEEK's questions on the coin glut in many states, but an official spokesperson for the ministry said the officials would respond when they were free from parliamentary priorities. “We are busy with the budget consultation procedures right now and I cannot talk about coins now,” said Subhash Chandra Garg, secretary, department of economic affairs.

Interestingly, it is said that the government can fix the problem without much trouble. Traders in Mumbai and some other cities recently approached the RBI complaining about the shortage of coins. Said Saon Ray, senior fellow at Indian Council of Applied Economic Research, “It would be a low-hanging fruit for the government—absorbing some of these coins from the glut areas and re-distributing them in places where there is a shortage.”

Arvind Jain

Arvind Jain