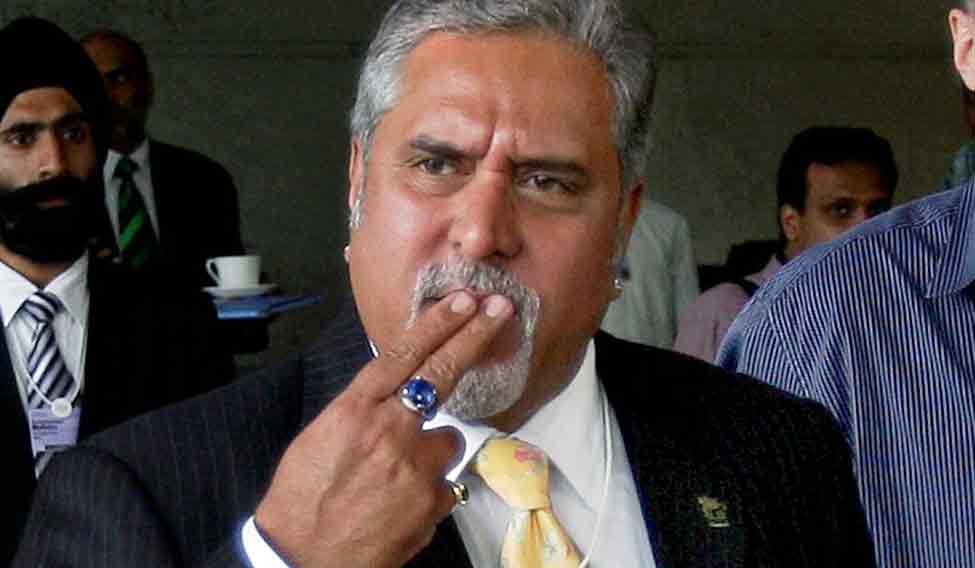

When United Bank of India filed a winding-up petition against United Breweries Holdings in 2013, little did it know that UB Group promoter Vijay Mallya would flee the country and that it would be tough to recover even a part of the dues. Three years since, the case is pending with the Karnataka High Court.

Recently, banks found no takers when they tried to auction Mallya’s secured assets, such as Kingfisher House in Mumbai, using powers given to them by the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (SARFAESI) Act. The value of the assets had so fallen that there were no bidders.

“Existing laws have proved ineffective when it comes to recovering money from defaulters,” said Deepak Narang, former executive director, United Bank of India. “A comprehensive regulation was needed to save the banking system from collapsing under the NPA [non-performing assets] burden.”

According to a World Bank study, creditors to defaulting companies in India recover just 25.7 cents to a dollar, compared with 80.4 cents in the US. Also, the recovery time in India is long: 4.3 years, as compared with 1.5 years in the US.

The Bankruptcy and Insolvency Code 2016, recently passed by the Rajya Sabha, is expected to ease the recovery woes. Causing trouble for the banks was a multiplicity of laws: the SARFAESI Act, the Sick Industrial Companies Act and the Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs). “Four different forums—the High Courts, the Company Law Board, the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction, and the Debt Recovery Tribunal—have overlapping jurisdiction, which gives rise to systemic delays and complexities. Plus, there was no law to deal with individual and partnership bankruptcy cases,” said Harsh Pais, partner at the legal firm Trilegal.

The new law plugs the gaps and provides a framework for banks to recover dues under a strict timeline. It not only empowers bankers, but also gives an opportunity to the companies to start afresh. For instance, if a company is not in a position to service its debt, lenders can file for an insolvency resolution proceeding (IRP) with the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT). An IRP can also be triggered by the company if it is unable to pay off loans.

After the IRP is filed, the tribunal appoints an insolvency resolution professional who works with promoters and lenders. The company and the creditors get 180 days from the date of filing the IRP to work on a revival plan. “During those 180 days, there is a moratorium on all assets of the company, meaning the borrower cannot sell, lease or transfer assets. All business decisions are taken by a creditors’ committee comprising financial creditors with voting rights in proportion to their exposure,” said Kalpesh Mehta, partner at Deloitte Haskins & Sells.

Within 180 days, 75 per cent of the creditors have to agree to a revival plan. If it does not happen, the company’s assets will be sold to pay off creditors and others who are owed money. “While the law seems to be watertight, there is a whole lot of infrastructure that needs to be put in place before things start moving on the ground,” said Nikhil Shah, managing director at Alvarez and Marsal India. “First, NCLTs need to be set up. Second, there has to be a new regulator in the form of an insolvency and bankruptcy board of India, which will regulate insolvency professionals and information utilities. And third, the law also proposes information utilities that would store all credit information about corporates.”