Now that the hurly-burly’s done and the battle has been lost and won, it is time to turn our attention to the elephant in our courtrooms—the contempt of court.

But first, a word on what the country has been through these last few weeks: A contempt of court petition is moved against Advocate Prashant Bhushan and, after spending many precious hours on arguments and hearings, the Hon. Supreme Court convicts him. So far so good. But then we see the Supreme Court requesting, almost entreating, the offender to kindly tender an apology to it so that it can avoid punishing him.

Bhushan then takes the high moral stand and refuses to apologise, declaring like Mahatma Gandhi that he would willingly accept any punishment the court handed down, but his conscience will not permit him to apologise. The country then waits to see Bhushan being made an example of and taken in chains to Tihar, Delhi’s Tower.

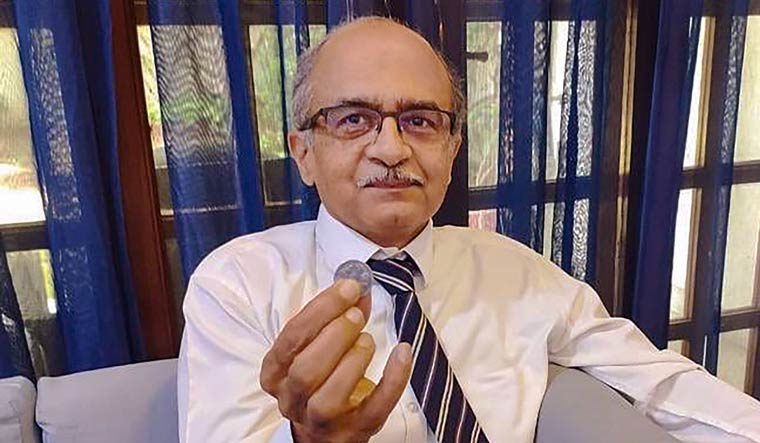

However, that would have made him a greater star than he already was, with the addition of the halo of martyrdom. So the court instead asks Bhushan to pay a fine of just one rupee.

The elephant had delivered a mouse.

Did the court punish the offender? Yes. Did the court punish the offender? No.

One rupee is a very trivial amount for anyone, and certainly for Bhushan, a crorepati many times over, as I believe most senior advocates in our superior courts are. The only real difficulty that Bhushan would have in paying the amount would be to find a Re 1 coin. It would be difficult these days. Even shopkeepers give you two toffees when they must give you a rupee back as change. So, two toffees should get Bhushan off the hook.

Prashant Bhushan was asked to pay a fine of Re 1 by the Supreme Court | PTI

Prashant Bhushan was asked to pay a fine of Re 1 by the Supreme Court | PTI

Is the contempt of India’s Supreme Court worth only one rupee? That would be a sad reflection on the judiciary. Or did the court overstretch itself in the matter of contempt?

This “crime” and its “punishment” has rightly triggered a wide debate. The Supreme Court held Bhushan guilty of contempt because his tweets were based on “distorted” facts. Would the conclusion have been different if it were true? Would his tweet still fall within the realm of criminal contempt, if they were, indeed, facts? A bare reading of Contempt of Court Act, 1971 would show that even a tweet based on facts would still be criminal contempt.

This is strange. Is the law of the contempt of court attempting to hide truth? Suppressio Veri is Suggestio Falsi.

Section 2I of the Contempt of Court Act, 1971 defines Criminal Contempt to mean the publication (whether by words, spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise) of any matter or the doing of any other act whatsoever which: (i) scandalises or tends to scandalise, or lowers or tends to lower the authority of, any court; or (ii) prejudices, or interferes or tends to interfere with, the due course of any judicial proceeding; or (iii) interferes or tends to interfere with, or obstructs or tends to obstruct, the administration of justice in any other manner.

This definition is prone to wide interpretation as recognised by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of S. Mulgaokar (1978) 3 SCC 339. The laws of contempt, therefore, need to be revisited striking a balance between upholding the majesty of the courts and administration of justice, and the natural, primordial, basic, inherent and inalienable right of freedom of expression guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. The fundamental right of freedom of expression juxtaposed with the right to fair and legitimate criticism that an individual possesses should not be stifled. On the contrary, a strong effort should be made by the courts themselves to protect it.

The Supreme Court highlighted this, in the case of Brahma Prakash Sharma 1953 SCR 1169, drawing a distinction between what constitutes libel on the judge and what constitutes contempt of court. The court rightly held therein that, “it is not by stifling criticism that confidence in courts can be created”.

Every Indian has an inalienable right to a fair justice delivery system. Such right is omnipresent in with the Constitution which places the individual at the forefront, guaranteeing civil and political rights. Not only the State but the Judiciary also should be accountable to the individual. To argue that the judiciary cannot be subject to fair and legitimate criticism would undermine the rights of the citizen.

This reinforces the argument that the law of contempt needs to be revisited, granting the citizen the right to question motives, if any, as this would indeed deepen democracy.

In western democracies, the law of contempt has evolved substantially. In the United Kingdom for instance, the judiciary was recently dubbed by some tabloids as “You Old Fools”, “Enemies of the People”. But no action of contempt was initiated against them, though doubtless such comments are excessive. The courts judiciously and sensibly ignored the stories. Dogs bark when elephants walk. But elephants walk on.

Former US president Theodore Roosevelt raged against the dissenting opinion of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in the case of Northern Securities, declaring “I could carve out of a banana a judge, with more backbone than that.” And President Donald Trump recently called District Judge Jon S. Tigar, an “Obama judge”.

Have such statements undermined the American judiciary? On the contrary. Such freedom has only deepened democracy, apart from strengthening the justice delivery system. As Chief Justice John Roberts declared, “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges. What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them. That independent judiciary is something we should all be thankful for.”

As he further observed that criticism comes with the territory and that, “all members of the court will continue to do their job, without fear or favour, from whatever quarter”.

These statements apply as much to the Supreme Court of India as to the United States. Thus, even the most powerful men in the world cannot in any manner destabilise the foundations of our courts.

The contempt laws of India are archaic and need to be revisited. These laws should protect the citizenry from any possible disquieting inclination of any institution (including the judiciary) from silencing criticism or dissent, apart from protecting such dissenters from harassment and intimidation. “An enforced silence would probably engender resentment, suspicion, and contempt for the bench, not the respect it seeks”.

This is what the courts in India would indeed desire, respect that is earned and not forced.

(With inputs from Sherry Oommen of the High Court of Kerala on legal aspects of contempt of court)

M.P. Joseph, (former IAS) is an ex-UN and Indian Civil Servant

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of THE WEEK