Speaking to The Guardian after winning the 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature, Tanzanian novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah remarked: "I could do with more readers." Gurnah—who has published 10 novels, several short stories and essays—started writing in English as a 21-year-old refugee in England; he was forced to flee the island of Zanzibar after the revolution which overthrew the monarchy. A distinguished academic and critic, his work has been recognised for an "uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents". Diasporic literature, themes of exile, memory and migration are intrinsic to his oeuvre.

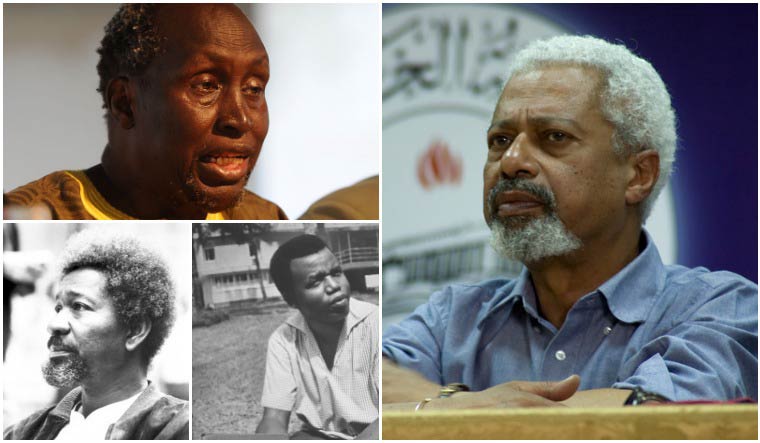

Gurnah is the seventh African to win the Nobel in literature, after Albert Camus (born to French parents in Algeria) in 1957, Wole Soyinka (1986), Naguib Mahfouz (1988), Nadine Gordimer (1991), J.M. Coetzee (2003), and Doris Lessing (2007). And, he is the second black African writer after Soyinka to win the prestigious award. While Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart, set in Nigeria, might have been our introduction to African literature in English, Gurnah's win reminds us once again to pay attention to the diversity of literary narratives emerging out of the continent. For now, one can check out Soyinka's latest, Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth, which comes almost 50 years after his last novel.

In an interview with THE WEEK, Madhu Krishnan—professor of African, World and Comparative Literatures in the Department of English, University of Bristol—tells us more about the evolving art of African literary writing and its place in the world. She is currently working on a five-year project, funded by the ERC, titled ‘Literary activism in Sub-Saharan Africa: Commons, Publics and Networks of Practice’.

Madhu Krishnan, professor of African, World and Comparative Literatures at the University of Bristol

Madhu Krishnan, professor of African, World and Comparative Literatures at the University of Bristol

Do you feel Gurnah’s Nobel victory is good news for African literature on the world stage? Will it really help generate more interest and readership for lesser-known authors from the continent?

It would be impossible to suggest that the Nobel win will not increase the visibility of African literatures on a world stage, or at least [professor] Gurnah's visibility. Already, we are hearing stories of his books selling out in various United States markets, and there has certainly been an increase in interest in the United Kingdom [no doubt linked to the level of publicity here around his win]. The larger question is how long this increase in interest lasts. It has been well documented that large prize wins have an immediate net positive impact for sales of the winner's work, but the long-term impact can be less positive and, in some cases, even negative. I am sceptical that an institution like the Nobel can help generate interest in less-visible writers and literatures, particularly those which take a more deliberately radical aesthetic or ideology. I would also contest the idea that [professor] Gurnah is himself “lesser-known”. Certain, amongst African literary readerships, he is extremely well known! The question of how known a writer is or isn't is a matter of perspective and a matter of scale. Within certain ecologies, something which, say, the global literary market deems 'unknown' or 'peripheral' might have far more purchase and relevance, and a greater audience. So, we need to be careful when we speak in these terms about who we are centering and from whose perspective we are speaking. I would point to this piece in Brittle Paper, which has collated over 100 African writers' responses to the win—not really lesser known, I would say!

How did the 1986 Nobel win for Wole Soyinka change the global reception of African literary narratives in English?

I am not sure that it did change the reception of African literary narratives. It might be more accurate to say that [professor] Soyinka's win gave certain amounts of intellectual and social capital to African literature, as a market category, but one could argue that this was a process that had already begun decades ago, with the canonisation of writers like Chinua Achebe, amongst others. Perhaps the most important thing about [professor] Soyinka's win was the way in which his work refuted some of the more peculiar ways in which African literatures are read. Here, I am thinking about the ways in which, certainly through the 80s, but happily less so frequently today, African literatures have been read as sociological or anthropological data, rather than artistic or literary works. Of course, African literary writing, like all writing, intersects with the political, and [professor] Soyinka's work is deeply engaged; at the same time, his explicit modernity and highly crafted aesthetics force readers into thinking more deeply about the art of African writing, one might argue.

How relevant is the language question for contemporary African novelists writing in English in a post-colonial world? Is conveying the African experience in English the only way to become a literary giant on a global stage?

I think that the language question is one which comes in two parts. In structural and institutional terms, it is hard to refute the idea that English, as a language, has the largest market share and reach. It is simply a fact that, dollar for dollar, writing in English outstrips other languages. So, there is a question of infrastructure and economics to think about, which is one thing. The other question, however, is about the language of expression. Firstly, I would contend that it is dangerous to see English as anything but an African language—if an African writer chooses to write in it. Why shouldn't an African writer own English as much as a British writer or USian writer? Certainly, myriad African writers have shown the ways in which they can take English and transform it into a language of their own, moulding it and pushing its boundaries. All languages are fundamentally plural, and all languages evolve; English is no different. I don't think it is for me to say how a writer should or should not 'convey their African experience'. This is fundamentally a question about art. Yes, it is mediated by infrastructural and economic factors. And indeed, we should not downplay the importance of areas such as education, which can shape the languages within which writers feel able to write. But, there are so many writers who today say that we can be more radical in our thinking and work in different ways. Most famous here, of course, is Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, whose creative writing is composed and written first in Gĩkũyũ and then translated into other languages, but also other figures such as Boubacar Boris Diop, who himself writes in Wolof and whose publishing house has been transformative in advocating for translation into and out of the language, or Richard Ali A. Mutu, who writes in Lingala and published the first novel in Lingala to be translated into English. The works of these people, amongst many other literary activists including Zukiswa Wanner, Edwige Dro, Bibi Bakare-Yusuf, Munyao Kilolo and so many others, show that English is not the only way. Equally, their work shows the importance of developing infrastructures and translation in de-centering English, or at least offering alternatives for writers.

Also, how problematic is it to treat African writing in English as a single domain, just like monolithic descriptions of Africa in mainstream media is frowned upon?

Definitely it is problematic. What we mean by 'African experience' is not monolithic. A novel that is set in, say, Southwest Cameroon or Ghana or Liberia is going to be radically different in terms of its cultural intersections and framings to a novel set in Kenya or Uganda or South Sudan. Africa is not a country; it is the second largest continent in the world and home to myriad languages, cultures and experiences, so of course literary writing is going to reflect that diversity.

Some modern African writers you might like to recommend?

This is a hard question! There are so many excellent writers. Some writers whose work I have enjoyed lately include Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor [I am obsessed with her book, The Dragonfly Sea] and Akwaeke Emezi. I love Zukiswa Wanner's travelogue, Hardly Working. There are really too many to count, to be honest!