Born in 1909 in a conservative north-Calcutta household and married off at 15, Ashapoorna Debi was never allowed to go to school. Yet she gifted some of the most unforgettable stories in the canon of Bengali literature. It is said that she learnt her alphabets by listening to her brothers, who read aloud their lessons with their private tutors. She was confined within the four walls of domesticity for much of her life and yet ended up writing more than 150 novels and 1,500 short stories in a career spanning 70 years. Her first published piece was a poem in a children's magazine when she was 13. She called herself 'Saraswati's Stenographer', referring to the goddess of knowledge and learning.

At a time when women's liberation movement hadn't even gained traction in India, Debi was already dashing off stories about the lives of women who persistently swam against the current in stifling, middle-class Bengali households, the andar mahal or the inner chamber. One such story is that of Subarnolata from her magnum opus, the Debi trilogy, consisting of three novels—Prathom Protishruti, Subarnolata and Bakul Katha.

On June 29, the India Habitat Centre in Delhi revived a 1999 Hindi stage adaptation of Subarnolata. Directed by Kirti Jain with the Kshitij Theatre Group, the play did not veer much from the original story. It continued to evoke fear and unease in the way the vivacious, fearless protagonist of the eponymously titled play suffers continual indignities in her marital home. Married off as a child and full of wit and wonder, Subarnolata wants a house with a balcony, she craves the sea, wants to read, spin the charkha and sing songs of freedom. But she has to persistently and vehemently fight and cry and suffer beatings to achieve any of this in her deeply patriarchal house, made more fearsome by her thuggish mother-in-law who is admirably cast in the play.

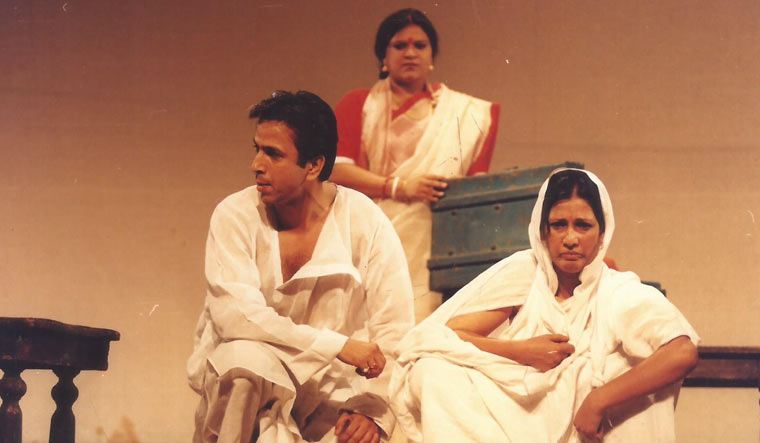

An earlier stage adaptation of 'Subarnolata'

An earlier stage adaptation of 'Subarnolata'

In all three books, Pratham Pratisruti (The First Promise, 1964), Subarnalata (1967) and Bakul Katha (The Story of Bakul, 1974), the act of writing has been used a weapon by the resilient women in the story. Pratham Pratisruti's Satyabati did not have access to ink. So she first writes on taalpaat or palm leaves. She would sometimes use the sap made from a paste of leaves to write. Her daughter Subarnolata in the next book, while does have access to ink, hides and writes in the shadows of the night and destroys everything she produces in her misery. And Bakul in the next book, while a writer herself, suffers a great deal at the hands of her publisher.

The play flows seamlessly with women in sarees draped the traditional Bengali way, speaking in Hindi, with Bangla songs of social unrest playing in the background. This pattern is suddenly broken with tunes of shehnai, north Indian style, in a scene abuzz with marriage preps. The constant shuffling of two cultures in costume, music, dialogue and stage-setting adds much energy and verve. Jain admits her new cast did wonder why they should revisit the script written in 1999. "For me it's a different kind of experience of working through a text where you understand the lives of the actors and the life of the characters in the play," says Jain. "Re-looking the text in today's context has more to do with how young people would respond to the plight of this woman. It is this interaction with the actors which brings forth newer nuances. For instance, the Subarnalata in this play is more angry. Maybe, back in 1999, we were not looking at a very aggressive Subarnalata. Understanding the psyche of the actors participating in this play was the exciting part for me. That becomes the reflection of the society for which you are presenting it."

While the play is set in a time and space we longer inhabit or identity with, Subarnolata still speaks to us. Every time a woman asserts her autonomy and is forced to cow down because of her gender, it is same sense of unfreedom Debi had railed against in her timeless tales.