Tibetan calligrapher Jamyang Dorgee Chakrishar is on a mission. He wants Tibetan calligraphy to attain as much respect and renown as a visual art form as its Chinese or Japanese counterpart.

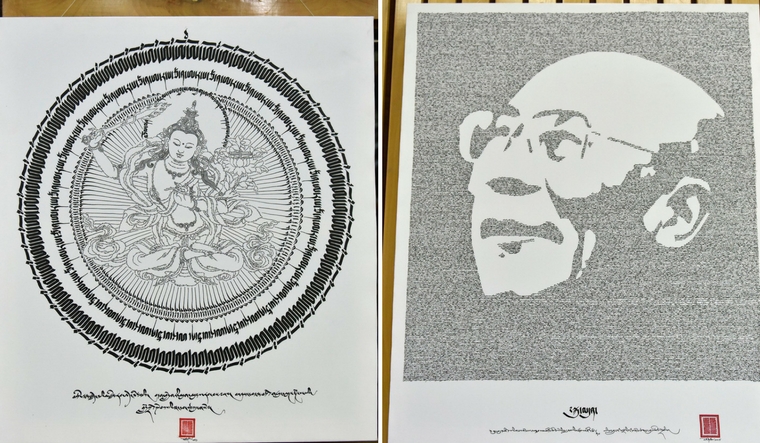

Dorgee was in the limelight in 2010 when he created the world's longest calligraphy scroll at 165m comprising prayers by 33 Tibetan spiritual masters for the long life of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. It was made using handmade Tibetan lokta paper and contained 65,000 Tibetan characters.

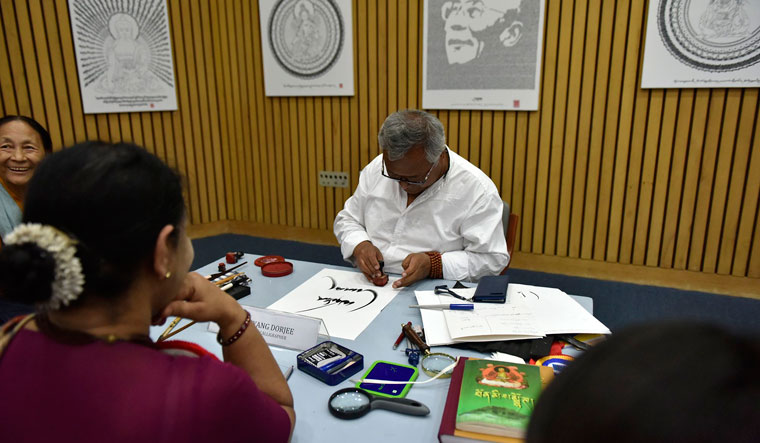

At the ongoing "Cultural Festival of Tibet" at Delhi's India International Centre, organised in collaboration with the Central Tibetan Administration, Dorgee is surrounded with the quintessential tools of the trade—black ink, white paper and the red seal which he uses to imprint his name. But where is the famous scroll? "It weighs 52 kilos," he laughs. "I couldn't have carried it here."

They say calligraphers are the embellishers of the 'Word of God'. In the 15th and 16th century, people who invented new calligraphic styles or even expanded and experimented with already existing ones in the Islamic courts of Persia or Turkey were considered figures of divinity and found many royal patrons and garnered great scholarly attention. But Tibetan calligraphy is not as old or illustrious as Islamic or Chinese calligraphy. The Tibetan script, composed in the 7th century, has undergone many transformations but has remained strictly within the confines of a "traditional handwriting" which is either good, bad or passable.

But Dorgee, 68, who has been practising Tibetan calligraphy as a hobby since his school days in Shimla, after his family fled Lhasa in 1959, wants to change that. "For thousands of years, we have devoted too much time in developing the inner science and neglecting the visual arts...we also have the capacity to be with the Japanese and the Chinese in the domain of calligraphy," says Dorgee who was a former joint secretary under the government of Sikkim and later worked as the director of Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts in Dharamshala. Commenting on how few practitioners of the art form exist, Dorgee says with a hint of sarcasm: "Our spiritual masters like to do it a little bit, but it's not necessary for them to have a perfect handwriting because their brush is divine."

Dorgee retired as a bureaucrat in 2009 and "reformatted" himself into an artist. He currently runs Lhatsun Dharma Centre, in Rabongla, south Sikkim, which teaches Buddhist texts and chantings. Having trained under great masters like Geshe Lobsang Tharchin and professor Samdhong Rinpoche during his Shimla days, Dorgee is now considered to be a master calligrapher who uses the u-med style of brushwork to depict a more free-flowing, artistic interpretation of the Tibetan language, reflective of his devotion to Buddhist wisdom and deities. He has also pioneered the delineation of Buddhist deities in a meticulously detailed style called miniature calligraphy.

Dorgee says that traditional Tibetan handwriting or script is based on the Devanagari model from India. " But Tibet has not been expressive enough in telling the world that their script is from Devanagari. Even Indian linguists make no mention of the fact," he rues.

For now though, Dorgee wants to make Tibetan or Bhoti calligraphy popular through workshops, seminars and exhibitions. The inclusion of Bhoti, the Tibetic language spoken from Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh, in the 8th schedule of the Indian Constitution will also go a long way in propagating the richness of Tibetan calligraphy, says Dorgee.

He is now looking forward to April 30 which will be celebrated as Tibetan Calligraphy Day for the first time in India. To be held in Darjeeling, it is being organised by Manjushree Centre for Tibetan Culture. But why April 30? "Because it represents the 30 consonants and four vowels in the Tibetan script," says Dorgee.