To sit still is a privilege, you realise when you meet Jitendra Sethi, 27. For the last 22 years, he has been fighting his own body to keep still. Jitendra suffers from Tourette Syndrome, a disorder that causes motor and vocal tics—repetitive, sudden, brief movements that are difficult to control.

Jitendra’s tics were so severe that every ten seconds or so his whole body would convulse with his head jerking towards his shoulder and tilting back, and his right hand moving violently. He often involuntarily banged his head on the wall or thumped his chest. Repeated hitting often led to severe bruising on his body, yet Jitendra could do little to stop his own movements. Misunderstood to be naughty and then difficult, he faced constant criticism and ridicule. The constant jeers and stares affected him but Jitendra did not lose hope. He kept searching for answers and treatments and finally became the first person to be operated for Tourette Syndrome in India.

Jitendra meets us at his two-bedroom home in MTNL quarters in Powai where he lives with his family of twelve including his parents, three brothers and their families. Dressed in a T-shirt and casual pants, he looks like any other individual, save the two semicircular scars on his shaved head, a remnant from the deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery he underwent in July. He is nervous and fidgets a little but there are no signs of the tics that made his life a hell. “People used to ask me, 'Why don’t you control these movements?' They had no idea how much I was already trying to curb them. The pressure was tremendous,” he says.

Tourette Syndrome is a neuropsychiatric disorder that usually begins in childhood. It affects about 1 in 200 children but only a quarter of them have moderate to severe symptoms, which subside as they grow up and most do not require medical treatment. Some, like Jitendra, do not respond to treatment. “Tourette Syndrome is not difficult to diagnose, yet some patients are resistant to drugs and do not respond well to the treatment,” says Dr Sangeeta Rawat, head of the neurology department at King Edward Memorial Hospital, Mumbai. She cautions against assuming that DBS surgery is the ideal treatment for Tourette Syndrome. “DBS surgery is an accepted treatment for Parkinson’s Disease but there are risks involved and side effects post surgery. Other than the prohibitive cost, the battery of the pacemaker needs to be changed after a few years, which requires another surgery,” she says. But, for Jitendra, it was his only hope to lead a normal life.

Till he was five, Jitendra was like any other active and naughty child. Being the youngest of four boys in the middle-class Sethi household, he was loved by all. He, however, started showing repetitive behaviour when he was in class one. It began with banging his head against the wall, banging his plate on the floor while eating and saying the same thing over and over again. His parents initially thought it was a temper tantrum. “When we asked him why he kept doing these movements, he said he was mimicking someone. Only until he was in class five that we realised there was a medical cause behind it,” says Saraswati Sethi, Jitendra's mother. They consulted general physicians, neurologists and psychiatrists, who gave him medicines but to no avail. “We took him to homeopathy, ayurveda and allopathy practitioners. They could not diagnose the condition,” says his father, Harihar Sethi, who works as linesman in the state telecom company. He confesses that they went to churches, dargahs, temples, and even to quacks, who claimed to ward off evil spirits. For years, Jitendra was under the treatment of a reputed neurologist, but drugs couldn’t control his movements and side effects were debilitating.

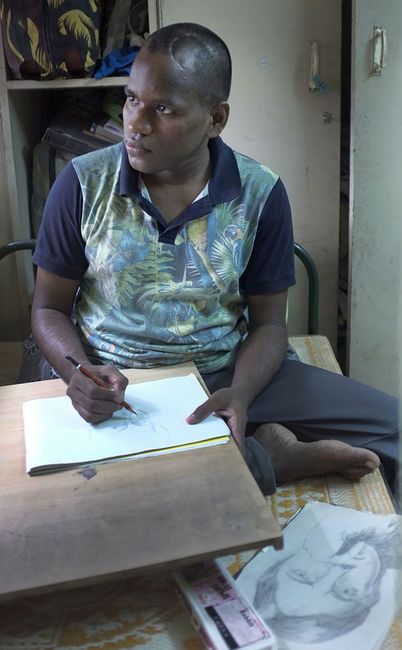

Jitendra's school days were a nightmare as children often made fun of him. “Teachers also did not really understand my behaviour. I used to sit on the last bench so that no one would notice me,” he says. Being unable to understand his own body also frustrated him and he often lost his temper. While the physical movements exhausted him, he found it difficult to sleep at night. An average student before, he failed thrice in his school exams because he was unable to write the answers owing to the involuntary movements of his hands. He became a recluse, keeping away from his friends and family. But some friends stood by him, including Shahid Shaikh, who would help him with his homework every night. Jitendra would lock his hands under the legs while sitting in the classroom, says his brother Karan Sethi. During exams, he would clutch a tuft of hair to prevent his hand from moving and finish the paper. Even though he couldn’t write, Jitendra was interested in sketching and his sketches won prizes in school and college.

At home, he would be online, reading and learning new things. Wanting to make friends, Jitendra started making fun of himself and his body. “I started mimicry and making others laugh and slowly other students started talking to me,” he says. But academically, he continued to struggle. Initially, he opted for science after his board exams but finally managed to complete his graduation in mass media. But after graduation, things went downhill as the medications prescribed by his neurologist made him drowsy and lethargic and had many side effects like weight gain and skin darkening. He soon found himself slipping into depression. He would lock himself in a room and he felt suicidal at times. He then quit the medicines and did a course in animation. His short films were shown across the institute and he found a job. But he had to quit after his tics made it impossible for him to work.

Tics talk: Jitendra Sethi is planning to make a documentary to create awareness about Tourette Syndrome | Amey Mansabdar

Tics talk: Jitendra Sethi is planning to make a documentary to create awareness about Tourette Syndrome | Amey Mansabdar

This time, Jitendra was determined to find a solution. He remembered the word tics that a US-returned doctor had mentioned when he was 12. The word led him to Tourette Sydrome, and he finally knew the name of the unknown disease that had imprisoned him for life. Thanks to the internet, he realised he was not alone and discovered a community of Tourette Syndrome patients from other countries. On interacting with them, he found out about DBS surgery. He searched for centres performing DBS surgery in India and decided to do it at Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai. His family gave him all the support he needed; the money saved up for a new house was used for his surgery.

“We were surprised by the severity of his tics and also his knowledge about the disease. He directly asked me the location I was going to place the electrode,” says Dr Paresh Doshi, functional neurosurgeon and director of neurosurgery at Jaslok Hospital. “DBS surgery is not a surgery to be offered on patient’s request. Each case has to be thoroughly examined according to international guidelines.” A team of psychiatrists, neuropsychologists and neurologists evaluated Jitendra. Dr Amit Desai, consultant psychiatrist, confirmed the severity of Tourette Syndrome and observed that Jitendra had elements of anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and that he had received all available treatments. Finally, Jitendra was cleared for the surgery and an MRI was performed to define the surgical target. It was decided that electrodes will be placed in the internal globus pallidus region of the brain. “While it is difficult to tell how it works, we have found that stimulating the GPi region leads to improvement in both motor and psychiatric manifestations of the disease,” says Doshi, who has done more than 350 DBS surgeries.

On July 15, Jitendra was taken to the operation room and a stereotactic frame was attached on his head to bore a hole in the skull. The doctors decided to perform an ‘awake’ surgery, whereby Jitendra would remain conscious so that the doctors would get his response to the area where they place the electrode. It was a challenge to ensure that Jitendra remained still during the surgery but he managed to do so, thanks to drugs and his determination. Two electrodes were placed on each side of his brain after assessing their response. Post surgery, Jitendra underwent the implantation of a pacemaker in his chest; it was switched on the next day. The results were instantaneous—Jitendra could sit still for minutes together, a first in many years. More than a month later, Jitendra says 50-60 per cent of his symptoms have resolved.

Jitendra is excited about starting his life anew. He is part of an event management company with his friends and is also looking for a full-time job in animation. Even though his right hand still has some tics and his verbal fluency is affected, his doctors have told him to be patient till the pacemaker is fully adjusted. Jitendra is now making a documentary on his journey to create awareness about Tourette Syndrome in India. Recently when he was out having dinner with his friends, he says, for the first time he wasn’t the centre of attention and he absolutely loved the feeling.

LOOK FOR EARLY SIGNS

A neuropsychiatric disorder characterised by motor and verbal tics, Tourette Syndrome usually begins in childhood. Simple motor tics include eye blinking, shrugging, head or shoulder jerking whereas complex motor tics include facial grimacing with shrugging, jumping, hopping, bending and twisting. Simple vocal tics include sniffing, throat clearing and grunting while complex vocal tics include using inappropriate language, swearing and repeating phrases. Tics are often accompanied by psychiatric conditions like hyperactivity, obsessive compulsive disorder, inattention and impulsivity. Many of them also suffer from anxiety and depression. About 1 in 200 children suffer from Tourette Syndrome but only a quarter of them have moderate to severe symptoms, which subside as they grow up and most do not require medical treatment. Some cases, however, require significant medical and surgical intervention.

BRAIN WORK

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) surgery involves implanting electrodes that pass electric impulses in a specific area of the brain. These impulses are controlled by a pacemaker. DBS is used to treat many neurological and movement disorders like Parkinson’s Disease, dystonia and tremors. It is also used to treat migraine, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder and Tourette Syndrome when other modes of treatments fail.

A multidisciplinary team of psychiatrists, neurologists and neuropsychologists first evaluates the severity of the symptoms and the drugs and duration of treatment as well as presence of other psychiatric conditions. Only 120 patients with Tourette Syndrome have undergone DBS in the world. The levels of improvement vary in patients, and doctors are yet to find the most effective target area in the brain for Tourette Syndrome. Patients must be counselled about the risks, side effects and the expected outcome of the surgery. Patients require multiple programming and medication adjustments.