It worked like a vaccine of sorts—a sugary solution with a probiotic bacterial strain for newborn babies to prevent sepsis. This was in Odisha, back in 2008. US-based paediatrician Dr Pinaki Panigrahi, who had already been working on sepsis and necrotising enterocolitis (inflammation of small intestine and colon) in neonates for two decades by then, knew enough about good bacteria in the gut and their therapeutic properties.

Now, Panigrahi and his team had their task cut out—finding good bacteria for the transfer of the good stuff. After collecting and evaluating several hundred samples of potentially beneficial bacterial strains, both off the market and from babies, the healing bugs were found in the unlikeliest of places— in the babies’ dirty diapers. The bacterial strains were then isolated from the stool, mixed with non-absorbable sugar to enhance efficacy and fed to the babies along with breast milk. The solution worked like a charm—besides preventing sepsis, the babies also reported a drop in several other infections, including respiratory tract infections.

For decades, bacteria have been shunned, feared and abhorred for causing everything from tooth decay to epidemics that have wiped out entire generations and, at times, altered the course of history. World over though, scientists such as Panigrahi have found redemption for certain species of bacteria by reporting the crucial role they play inside our bodies in their clinical trials. Research has shown that friendly bacteria that colonise our gut interact with our gut immune mucosa, thereby playing a huge role in making us fat or thin, happy or sad, diseased or healthy.

Microbes, we now know, are all over us. Even breast milk, says Panigrahi, once thought to be a sterile medium, has bacteria. Together, these microbes such as bacteria, fungi, viruses outnumber human cells—the human body is made up of 10 trillion cells and 100 trillion microbes. A majority of the microbial population (about 90 per cent, say experts) though resides in our gut; up to 2kg of our body weight is composed of the gut microbial population that holds the key to human immunity.

These microbes, primarily bacteria, break down the food we eat, release the by-products into our system, produce vitamins, and set-off complex processes in our body that help us stay healthy, or make us diseased. They can also explain why certain drugs such as antibiotics will not work on us. Experts are trying to understand how these processes can be aided, abetted, or turned around in a bid to find cures and prevent several diseases including depression, Parkinson’s, autism, diabetes and obesity.

In India, too, similar efforts are underway, beginning with studying the inhabitants of Indian gut universe—possibly the most diverse in the world. Dr Bhabatosh Das, a microbiologist with Translational Health Science and Technology Institute, Faridabad, has some crucial insights into the Indian gut. Das, 41, is the lead author of a first-of-its-kind study on the Indian gut microbiome, which looked at the gut flora of healthy adults in rural and urban settings. Das, who returned from France—where he had worked on the subject of gut microbiome—in 2012, figured that not much had been done on the gut of Indian people and decided to take it up.

After smaller studies on the gut flora of undernourished children, Das and his team started work on the big one—their study was big both in terms of the range of samples and the technique used for studying the bacterial genomes—that was published last year. The researchers collected and analysed samples (faecal matter, richest source of gut bacteria) from three distinct sites—Leh in Ladakh, and urban and rural people in Ballabhgarh in Haryana.

The results were striking. “We found that the Indian gut flora is more diverse than, say, that of the Americans or even the Europeans. Indian gut has close to 500 species of bacteria, while the Americans have about 400 species,” says Das.

Overall, the study showed the diverse species of bacteria that populate the gut of Indians, reflected the diverse dietary habits, and provided some clues for developing potential cures for a few diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome through faecal transplants or specific probiotics.

It also reinforced the fact that urban lifestyles were upsetting the crucial and delicate balance of healthy bacteria and microbes in the gut. The urban gut flora samples were less diverse in their bacterial population than the rural ones.

“We also found that the gut flora of vegetarians was more diverse when compared to that of the meat-eating populations,” says Das. In their study, researchers found that dietary habits directly affected the composition of the gut bacteria, from cooking oil to sweet tea, to dairy and meat, the bacterial population changed with specific habits. For instance, the bacteria Collinsella was found to be higher in those who consumed ghee, Sporobacter in those that used mustard oil, and Roseburia in those that used sunflower oil.

The study also showed that the Indian gut flora is dominated by Firmicutes, the class of bacteria that ferments carbohydrates and helps extract energy from food to be used by the body or stored in fat cells. “This is higher than in developed countries, primarily because Indians eat a high-fibre diet,” he says.

A healthy gut would have bacteria from four phyla—Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria, explains Das. You would think then that Firmicutes or specific bacterial species such as Collinsella or Prevotella are our friends. The more the better, right? Wrong. Firmicutes have been found in a higher proportion in the gut of obese persons. “In those suffering from undernourishment, Firmicutes are too less,” he says.

Prevotella, which is found to be in a relatively higher degree in the Indian gut because of our high-fibre diet, has also been observed in a higher degree in the gut of diabetics, especially those with type 1 diabetes, says Dr Yogesh Shouche, director, National Centre for Cell Science, Pune. The exact mechanism at work between the two though is still being studied, he says.

Instead of individual bacteria, it is the “optimal balance” of bacteria that defines a healthy gut, Das explains, lending credence to the grandmother’s advice of eating a diverse diet, based on season, location and even the time of the day.

The relationship between diet and gut microbiome though is complicated. “There are studies that have shown that animal-based and plant-based diet promote different microbiomes. However, in India, if we go by the frequency of meat consumption, even the so-called non vegetarians could be defined as vegetarians. It is only specific communities that consume meat on a regular basis,” says Shouche. Genetics, environment and geography also play key roles in shaping the gut environment.

Shouche’s own study points to how the gut flora can be affected even by the way we are born—a vaginal birth shows less diversity of microbial species in the infant’s gut, as compared to those born via a C-section.

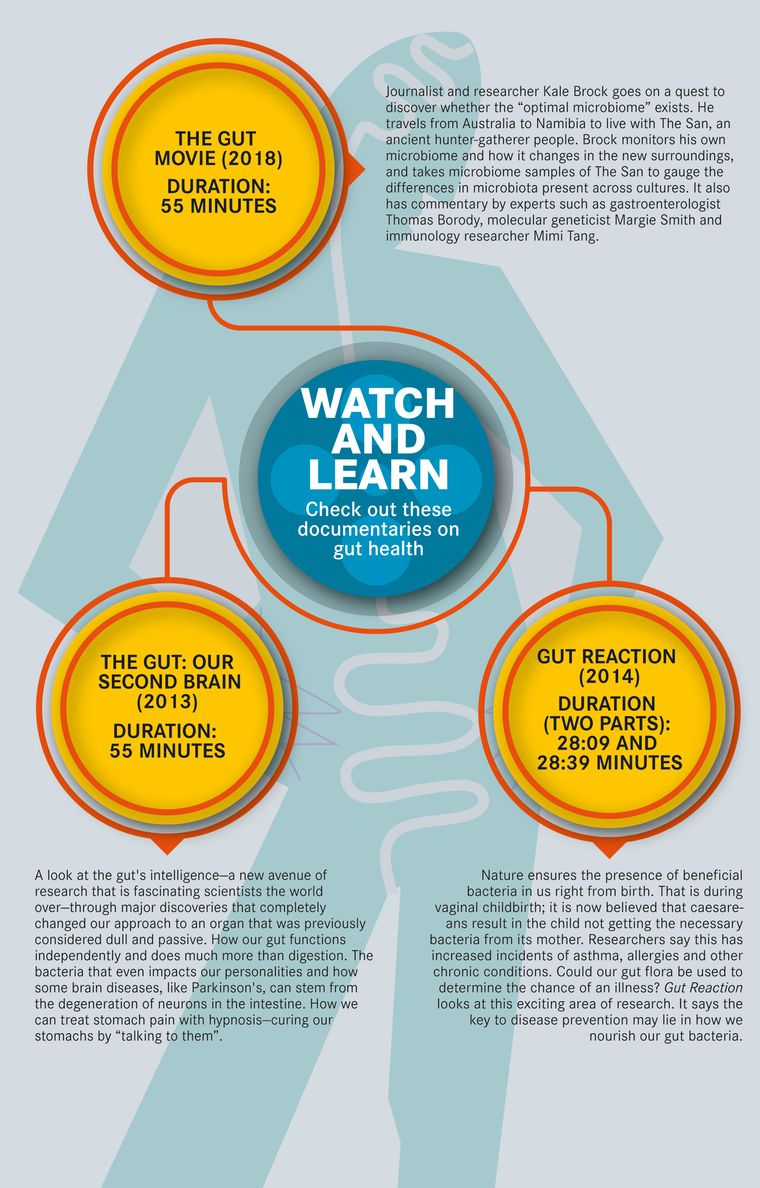

The link between gut bacteria and diseases of the brain such as Parkinson’s, depression, autism and dementia is also being studied. Earlier this year, The New York Times reported on research being do in the University of Chicago on how gut microbes were perhaps releasing a chemical that might be altering how immune cells work in the brain.

In November 2019, China gave conditional approval to a drug for Alzheimer’s, which contains a compound known as oligomannate that is derived from marine brown algae. The compound works by “rebalancing” microbes in the gut, including bacteria and viruses. Closer home, Dr Baby Chakrapani P.S. of the Cochin University of Science and Technology is preparing to start work on his latest research project—studying the link between the bacteria in the Indian gut and Parkinson’s disease.

The central question Chakrapani will be investigating is this: if the gut is like the “second brain” with all its neural connections, then wouldn’t a change in gut flora help prevent or at least detect brain diseases at an early stage for Indians? “There are 100 billion neurons in the gut. Not so much in the stomach, but in the large intestine where major exchanges take place,” says Chakrapani, who got interested in the project while observing a similar project being done at the University of Chicago. Chakrapani, along with Dr Shyam K. Nair, additional professor, neurology, Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute of Medical Sciences and Technology (SCTIMST), Thiruvananthapuram, has received a Rs1 crore grant from the Indian Council of Medical Research. The duo will investigate this question by taking several samples—faeces, blood, saliva and urine—from patients who will be recruited from the SCTIMST. “What we are assuming is that there are two to three pathways through which the transfer of metabolites from the gut to the brain can happen. Of these, the vagus nerve, the direct connection between the gut and the brain is one,” he says.

The vagus nerve is the longest and most complex of the 12 pairs of cranial nerves that emanate from the brain. It transmits information to or from the brain's surface to tissues and organs elsewhere in the body. The vagus nerve sends information from the gut to the brain, which is linked to dealing with stress, anxiety, and fear—hence the phrase 'gut feeling'. These signals help a person to recover from stressful and scary situations.

“The transfer could also be happening through body fluids. The exact mechanism of how certain protein aggregates (found in the gut of those with Parkinson’s) reach the brain is what we will be trying to understand over the next few years,” says Chakrapani.

Shouche, who is awaiting a nod from the Department of Biotechnology for an approximately Rs40 crore project on studying the Indian gut microbiome of 3,500 persons over two years, says as of now there is no comprehensive study to map the microbiome of different populations across the country. Studying the Indian gut itself is no mean task. “The most important challenge is diversity,” he says. “There is tremendous variation in genetic makeup, diet and geography. That makes it difficult to have a good representative sample to generate any meaningful data.”

The challenge, however, is a blessing in disguise, too, says Panigrahi, professor, department of paediatrics, division of neonatal-perinatal medicine and director, International Microbiome Research, Georgetown University Medical Center. “India, as one sub-continent, has 36 good-sized countries. Each one is different in its food habit, exposures, and from a socio-behavioural and environmental aspect as well. So, one could consider India to be a global platform to identify different types of microbiota, how they develop, and what they do,” says Panigrahi, who is credited with the ground-breaking study, published in Nature in 2017, on preventing sepsis through a synbiotic solution in 4,500 neonates in Odisha.

Other challenges for studying the Indian gut microbiome are the key issues of technique and funding. It is only in the last five years or so that advances in genome sequencing techniques have made it cheaper to study the gut microbiota. Das says one of the first studies he did on the Indian gut microbiome with merely 20 subjects cost Rs1 crore. “Now a similar study with a bigger sample size can be done in only Rs10 lakh,” he says.

The technique of sequencing genomes of bacteria has itself been crucial to the study of gut microbiome around the world. Dr G. Balakrish Nair, who was earlier with the Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology, Thiruvananthapuram, says that classical microbiology and its practitioners went only by lab cultures. “Microbiologists believed that what could be seen in a petri dish, cultured in a laboratory, was the only thing that could be studied,” he says.

Gut microbes, however, could not be cultured in a laboratory, and therefore were difficult to identify and study. Genome sequencing techniques offered a way out by enabling the microbiologists to study the entire genome structures of microbes. “That came as a huge shift in the way microbiologists worked, and the technique has brought nothing short of a renaissance in the way things were studied,” says Nair.

Elaborate studies on the Indian gut microbiome hold tremendous value. For instance, Das’s study has revealed that those from Leh could potentially be ideal donors for faecal transplants, owing to the balance of microbes in their gut. “In faecal transplants, you cannot isolate specific bacteria and so the entire microbiome of the donor is passed on to the recipient. Those in Leh did not have a high population of proteobacteria, which are known to have inflammatory properties, in their gut, and so they could prove to be ideal donors,” says Das.

More work on Indian gut microbiome would also lead to manufacture of probiotics with India-specific strains. “We are now working on genetically modifying the bacteria isolated from the Indian samples from our study, and analysing whether they can be used for therapeutic purposes,” says Das.

The more we know about specific strains of bacteria in our gut, the better probiotics—a controversial subject—can be developed. “As of now, there are no probiotics with India-specific strains available in the market. The ones that are available are from the populations of developed countries, and will not work for us,” says Shouche.

Studying the gut microbiome has never been an urgent and more pertinent exercise to be undertaken by researchers, say experts. “It is the science of the future,” says Nair. “And India, with its diverse gut flora, ought not to be left behind.”