On September 14, on the occasion of Hindi Divas, the Union home minister made a speech where he said, “There is need for our nation to have one language, so that foreign languages do not find a place.” Numerous non-Hindi-speaking political leaders and citizens were obviously indignant at the seeming threat of the imposition of one language in the linguistic kaleidoscope that is India. One may assume, though, that the real villain in the home minister’s somewhat bizarre fantasy of a linguistic invasion of India was poor-old-been-around-for-three-hundred-years-so-much-so-that-it-is-pretty-much-an-Indian-language: English.

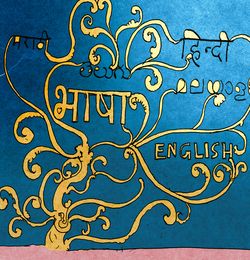

Of course English was the language of our colonisers and is a remnant of our enslavement by the British. Of course it is the language of global domination now. But to see a language merely as historical baggage and a monolithic object of historical oppression or domination is to miss the most fundamental and beautiful characteristic of language. That language is a living creature. It lives in the manner that each set of speaker infuses language with their own special individuality.

Language picks up the wheezing of the old rural grandmother who continues to smoke her hookah notwithstanding her asthma, and it lodges alongside the paan in the mouth of the lazy fat uncle from the city who tells tall tales. That is how language becomes accent and dialect. But, more importantly that is how it lives beyond empires and histories. That is how Jagannath, the Lord of Puri, becomes ‘juggernaut’ the noun that signifies ‘an overwhelming force’. And that is how the very British swear word ‘bugger’ became ‘beggair’ in a small town in Andhra Pradesh on the tongues of my father and his brother when they were eleven and ten respectively.

My dad and his brother went to St. Aloysius School in Vizag in the early 1960s. At school, they came across, via the gruff and frustrated vocabularies of the last of the British-trained teachers, the swear word ‘Bugger!’ It was always uttered in anger, always preceded a scolding and was often followed up with a punishment like a caning on the knuckles or the butt. The word ‘bugger’ (which is associated with sodomy and the sailor) soon became part of the lexicon of the boys of the middle-income housing colony on Fort Street in Visakhapatnam. Evidently, my father and his brother, whose Telugu had the chaste clarity of their Brahmin ancestors, were soon spouting the British cuss word with a Telugu twang.

One evening, my father and Krishna chinnanna (uncle) played cricket outside the house, and the younger brother Krishna got my 11-year-old father out on the second ball itself. “Bhaskaranuvvuouttu!”, said the victorious, bespectacled Krishna. Bhaskar, you are out.

“Nenuouttukaadura beggair (I’m not out, you bugger!),” yelled back my dad, unwilling to let go of the cherished bat so soon.

“Nuvvu beggairu (You are a bugger!),” glared his younger brother.

“Nuvvu cheat chesthunnavu guddi beggairu (You are cheating, you blind bugger),” my father’s 11-year-old form roared before the nine-year-old Krishna burst into angry sobs and lunged at my father.

Their mother appeared in the doorway. Now my baammaa spoke no English, only Telugu and a smattering of Marathi, which she had picked up when her husband, an auditor in the defence accounts department, was working in Pune. But, irritation makes you a linguist like nothing else can, and she had just finished cooking yet another meal for her large family.

She waved her ladle and yelled, “Vinandi iddaru beggiaerlu, lopalikivachchi annamtinnandarra (Listen, both you buggers! Come in and eat your food!)”

And that day, English, once again, became an Indian language. Because any language that finds its way into the vocabulary of an overworked, exasperated, vernacular young mother of five cannot possibly be a foreign invader, wherever its roots may lie.

The writer is an award-winning Bollywood actor and sometime writer and social commentator.