Asked why he was not firing FBI chief Edgar Hoover, President Lyndon Johnson said, “I’d rather have him inside the tent pissing out, than outside pissing in.” Hoover ran the FBI for 48 years as its boss, from 1924 when it was called the Bureau of Investigation, till his death in 1972.

Several presidents found Hoover useful; several others were scared of him. They knew, or they feared, that he had files on virtually everybody who was somebody in the US, especially about their sexual indiscretions.

Johnson’s successor Richard Nixon was lucky. Hoover died towards the end of Nixon’s term. Soon the Congress made a law that no FBI boss shall serve more than 10 years. Only the Yanks would do that—trust a guy, a paranoid and a blackmailer at that, to run their premier crime-detection agency for half a century. And then, give every successor of his a maximum of 10 years. Even their presidents get only eight years at the most.

Compare that with our CBI chiefs. Only two of its 28 bosses lasted five years. Some lasted a fortnight; one or two had only a few days; three were ‘acting’.

Truth be told, it was not the rogue Hoover that Americans trusted, but the robust institution he was running. They knew that the Hoovers would come and go, but the institution would go on.

We in India are the other way round. We place our trust in men, and ignore the institution. When the men fail, we do not mend or mind the men, but amend the laws, and make a mess of the institution.

That is what happened to the CBI. Like every institution on terra firma Indica, it had been scoring sometimes, and flopping sometimes. But every time it flopped, we took the institution to task, changed the laws that governed it and made a mess of it.

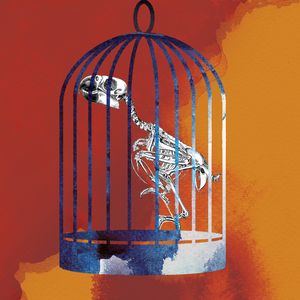

All three organs of the state share the blame. The original sin was the executive’s. As is their wont, our rulers have been using the CBI to raid political foes, and to close cases against friends. So much so that a chief justice called it a caged parrot.

But what have the judges been doing? When they found the agency was not chasing the hawala-moneyed politicians in the 1990s, they took it upon themselves, through the Vineet Narain judgment, to monitor the case. In the end, they could not convict even one among the dirty dozens. Yet the judges gave a host of directives on how to run the CBI and get it watched by the vigilance commission.

And the legislature? They have been making laws at the drop of a judgment. They gave statutory status to the vigilance commission, with its chief being selected by the prime minister, the home minister and the leader of the opposition. When they tried to reform the CBI as the judges advised, they included the chief justice in the selection committee—thus giving the go-by to the sanctified principle of separation of powers. Imagine, a judge selecting the police chief who is an arm of the executive. Incredibly, the judges concurred! As if the touch of the court would turn a rogue into a saint.

There is a protocol anachronism too. The CBI chief is selected by the prime minister, the leader of the opposition and the chief justice or his nominee. But the vigilance chief, who is notionally superior to the CBI chief, is selected by the prime minister, and two lesser mortals, inferior to the chief justice.

In the end, one is left to wonder: have the judge-selected CBI chiefs been any holier than their predecessors? Were Ranjit Sinha and Alok Verma not selected with the concurrence of the judges?

prasannan@theweek.in