Many years ago, a school bus fell into the Yamuna in Delhi. Several children trapped in it could not be pulled out to safety, because the bus windows had been barred. Following a public outrage, the city fathers ordered that school buses should not have their windows barred.

A few years later, a child was killed when he leaned out of the window of his school bus and his head hit a pole. Again, the city fathers listened to public opinion, and ordered all schools to have their bus windows barred.

Law-making in India, like the two executive orders cited above, which have been recounted earlier in this column, has become whimsical, reactive to public outcries, and self-defeating.

Narendra Modi’s latest ordinance is one such. Following a public outcry over the rape of a child in Kathua, Modi got an ordinance issued that would hang those who rape children. “There is now a government in Delhi that listens to people, and decides,” Modi claimed later.

Indeed, rulers in representative regimes ought to listen to public opinion. But, as Benjamin Disraeli, one of Britain’s greatest Prime Ministers, said, “what we call public opinion is generally public sentiment”.

Dead right! The public sentiment in the Kathua case has been anger—perfectly justified. The legislative sentiment that prevailed while making the law was also anger—not at all justified.

Regimes ought to make laws in wisdom, not in anger. Laws made in haste will be regretted in leisure; laws made in anger will be regretted in wisdom. So will be this law—a futile one with horrible consequences.

Futile, because this law will make no difference to the Kathua case, over which the public is angry. No law can be used for punishing a crime that had been committed before the law was made. Secondly, even without this law, the Kathua rapists can be hanged. They have committed pre-meditated murder, a capital crime.

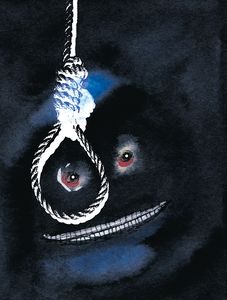

The consequences of the law could be horrible—not for rapists, but for rape victims. No rapist gives any thought for the law when he attempts to rape. But what if he does? Perish the thought, literally! He would realise that if the child names him afterwards, the law would hang him. So, what would he do? Horror of horrors! To save his own neck, he would kill the child then and there. The dead will tell no tales.

Modi’s ordinance is the third rape law made in anger. First, in a knee-jerk response to the Nirbhaya rape, Manmohan Singh amended the criminal law so as to enable courts to hang repeat rapists. Till date, we have not seen one rapist going to the gallows under that law.

The next was after the court let off one of the Nirbhaya rapists lightly, finding that he was only 16. Heeding to a public outcry, Modi got the juvenile law amended, so as to make 16-year-olds also subject to the laws that govern adults. No use. Several 16-year-olds have committed obnoxious crimes even after that.

Modi’s party-men say, the Kathua and Unnao cases have been communalised and politicised; hence the outcry. Pray, why not? The crimes, as alleged by the police and the prosecutors, also had a communal motive and political undertones. The Kathua fiends, as the charge-sheet goes, wanted to scare away Muslim goatherds from a Hindu habitat, and two ruling party MLAs came out in defence of the fiends. The Unnao case has a ruling party MLA as the accused, who used the police to silence the victim and torture her father.

The public anger was as much over the communal motive, and the shameful political conduct, as over the fiendish crimes. Any new law to address these?

India does not need more laws to reduce these crimes, and douse these bouts of public anger; India needs better law-enforcement. What dissuades the criminal is the certainty of punishment, not the severity of punishment.

prasannan@theweek.in