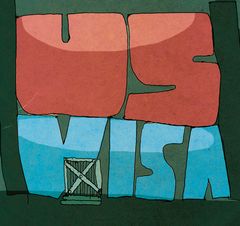

Before Donald Trump mercifully dropped a presidential-sized damp squib on the matter, the tit-for-tat strikes by US and Iran had the world on a razor’s edge. Amid the tension, one development got relatively little column space: Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, who is visiting India this week, could not get a US visa to attend a ministerial meeting at the United Nations.

While there was no outright refusal, it was put out that there was not enough time to process the visa. Iranian spokesmen countered that the application had been made well in time, and before the killing of Qassem Soleimani. Be that as it may, it was clear that right now the US would rather not have the affable and polished Zarif projecting his country’s viewpoint to the global diplomatic community and American media in Manhattan.

Not formally refusing the visa, but having Secretary of State Mike Pompeo whisper the demurral to the UN secretary general—a modus vivendi worked out by Dag Hammarskjöld for such cases—allowed the US to maintain the fig leaf that it respects the 1947 Host Country Agreement with the UN on the basis of which the organisation was headquartered in New York. Such agreements are the norm for hosting international organisations with the attendant advantages of global prestige, jobs and an economic injection; New York’s economy gets a huge boost from the world’s permanent delegations based there as well from the countless visiting delegates. While the US is obliged by the 1947 agreement to issue visas “as promptly as possible”for UN meetings, irrespective of the nature of bilateral relations with a particular country, a joint resolution of the US Congress of the same vintage retained a security caveat under which visas could be withheld. While legal experts have questioned such a security reservation, the US has continued to resort to it, including against Yasser Arafat in 1988. It remains a moot point whether a foreign minister attending a UN meeting can be construed a security threat.

By not resorting to a flat denial, the US intended to steer clear of the can of worms wriggling under the agreement. These contentious issues related to visas, customs and immigration; housing, transportation and parking; banking, taxes and insurance; restriction on movement, security and so on are regularly aired by member delegations in the UN Committee on Relations with the Host Country. The reports of the committee are a long litany of complaints against the US on the basis of which the UN secretary general has frequently reached out to Washington for relief but with minimal impact.

While the issues may not be new, the Trump administration has been pointedly aggressive in targeting countries seen as hostile to the US. Zarif’s movements were severely restricted during his earlier visit to New York in 2019; he was even refused permission to visit his ailing ambassador at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The Syrian foreign minister was denied a protective security detail, while the Syrian opposition delegation got one. Two Cuban diplomats were expelled on the familiar allegation of espionage under cover of UN work and other Cuban diplomats were confined to the borough of Manhattan. Venezuela has been added to the list of countries whose diplomats cannot travel beyond a 25-mile radius from Manhattan’s Columbus Circle. Finally, Russia and Iran held up the work of the UN’s First and Sixth Committees this autumn, alleging that large scale denial of visas to their diplomats had compromised their capability to handle multiple meetings. In the pinstriped world of diplomacy, such disruption, reminiscent of the Cold War, amounts to strong protest.

The writer is a former high commissioner of India to the UK and ambassador to the US