On the ground in Srinagar, bureaucrats and police officers alike tell us that they learnt from the mistakes the administration made in 2016, in the aftermath of the elimination of Burhan Wani, the dreaded Hizbul Mujahideen militant. Wani’s family was handed back his body, the funeral turned into a huge public event attended by an estimated two lakh people and protesters soon spilled over onto the streets. In the clashes that followed, there were 22 casualties in the first 48 hours; 37 lives were lost by the end of the first week. The Kashmir valley remained in turmoil for over two months.

This is the reason officials give for the extreme clampdown on communication, information and movement in the two weeks after Article 370 was struck down by a parliamentary majority. Principal Secretary and Jammu and Kashmir government spokesperson Rohit Kansal told me, “Not a single life has been lost in Kashmir. The restrictions seemed a fair price to pay.”

As someone who has been reporting from Kashmir for many years, I have seen curfew and snapped phone and internet lines invariably herald phases of volatility. That social media has been weaponised by a new generation of radicals and militants makes tackling mobile data and broadband lines a priority for security agencies. Irrespective of where one stands on Article 370 and the manner in which it was abrogated, I can see definite merit in prioritising law and order and containing violence.

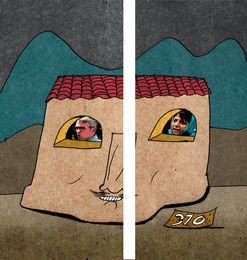

But the most significant departure from the past has been in the decision to arrest mainstream Kashmiri politicians, including three former chief ministers (Farooq and Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti), a host of legislators and civil society members. While the logic of preventive detention could have held in the first few days, it is unsustainable in a functioning democracy to keep them under lock and key without any specific charge against them. They may have been placed in comfortable environs—Omar Abdullah is at Hari Niwas, Mehbooba Mufti at Chashma Shahi and the others at the Centaur hotel—but the logic of denying them their political rights is now unfathomable. Especially because even with some variations in the position that their parties may have taken on autonomy or self rule, each of them has stood for India and sworn allegiance to the Indian Constitution and flag. Sajad Lone was the first separatist to experiment with electoral democracy, as far back as in 2002, when he fielded proxy candidates. As an all-India IAS topper (before he joined politics), Shah Faesal was a compelling alternative icon to a generation of young Kashmiris. The Abdullahs have been in alliance with both the BJP and the Congress at the Centre, and have always spoken as Indians. Mehbooba Mufti is probably the most extreme of all of those under arrest, but the BJP thought her Indian enough to run an alliance government with her, before abruptly walking out.

The point is not of principle alone, though of course that matters. The question is how is keeping these politicians under arrest—and weakening them into a position of complete irrelevance—strengthening the Indian state’s position? As one young man said to me, “Kashmir is like a pressure cooker.” Sooner or later the lid has to come off.

The government has also avoided answering precisely how many people have been arrested. Numbers are swirling about without verification, ranging from 700 to 4,000. Article 370 is gone. As J&K looks ahead at its next election—and a new phase in politics—the first priority must be to release those who have stood with India. With all their shortcomings and flaws, they are owed that.

editor@theweek.in