The Supreme Court’s verdict on the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi issue has been widely described as pragmatic. It has also been criticised for basing itself on faith rather than verifiable fact. All religious belief is based on faith. Hence, there is nothing inherently wrong in a court arriving at a view pertaining to religious belief on faith. As for the fact that the destruction of an existing structure called the Babri Masjid was an act of vandalism, the court has stuck to facts and opined that it was an illegal act.

Much has been written in the past few days on the pros and cons of the court verdict. One aspect of it has, however, not been commented upon. The very fact that all political parties and almost all religious organisations took the view that they would accept the verdict of the Supreme Court and gave the judiciary the last word on the subject is a testimony to the failure of both political and religious leadership.

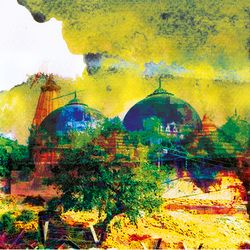

The movement for the construction of a temple to Lord Ram in Ayodhya at the site where the mosque stood grew in strength over the years mainly as a political movement. Indeed, it can even be argued that the original decision to construct a mosque in the very heart of Ayodhya, a holy place for Hindus, was itself a political act, taken by the rulers of the day. So both the decision to build the mosque, taken sometime in the first quarter of the 16th century, and the decision to replace it with a temple, taken in the middle of the 20th century, were both political acts of assertion.

Little wonder then that Lal Krishna Advani and the then leadership of the Bharatiya Janata Party decided to make the construction of a temple in the place of the mosque a political issue. The Archaeological Survey of India has established that the mosque itself was built on top of an existing structure. Even if this were not so, the temple protagonists could argue that they were making a political point with their demand to reverse an earlier political decision.

Given the politics of the entire matter, it would have been appropriate if the matter had been resolved politically between elected representatives from both communities. Such a political resolution and reconciliation would have added shine to India’s democratic institutions. Prime minister P.V. Narasimha Rao tried to resolve the matter politically but no political party was willing to confront, address and resolve the matter politically. He then appealed to community leaders to resolve differences. He appointed the late Naresh Chandra, a former Union cabinet secretary and later India’s ambassador to the United States, as an adviser in the Prime Minister’s Office and placed him in charge of finding a way out of the impasse. He was supported by the late P.V.R.K. Prasad, an IAS officer from Andhra Pradesh who had distinguished himself as the builder of modern and devotee-friendly facilities at the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams and thereby endeared himself to Hindu religious leaders across the country. But the Rao-Chandra-Prasad trio was unable to resolve matters since neither religious leaders nor political parties extended their support to them.

In the end, the matter landed at the doors of the judiciary. Over the years, it has travelled its way up within the judicial system and was finally settled by a five-member bench of the Supreme Court. For students of public policy, this is a good case study of how the judiciary steps in, time and again, to fill a policy vacuum created by the failure of political, administrative and social leadership.

Baru is an economist and a writer. He was adviser to former prime minister Manmohan Singh.