Sharad Yadav had spent anxious moments in his Delhi residence awaiting word from the Congress. He was relieved when the Congress gave his fledgling party two seats in Rajasthan, on par with Ajit Singh’s Rashtriya Lok Dal, and one more than Sharad Pawar’s Nationalist Congress Party. The Congress would contest the remaining 195 seats in the desert state, challenging the incumbent BJP. The Congress will also use its resources to back Yadav’s candidates, as he has no political infrastructure of his own.

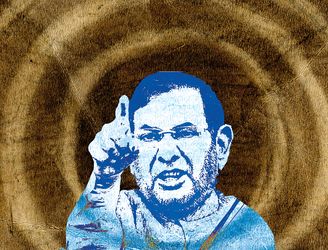

But, that is what makes Yadav unique in Indian politics. He belongs to the 1970’s generation of the Janata parivar, along with Nitish Kumar, Mulayam Singh Yadav, Lalu Prasad Yadav and Ram Vilas Paswan. Yadav has rubbed shoulders with the greats of the opposition from Jayaprakash Narayan to Atal Bihari Vajpayee in the last four decades, winning seven Lok Sabha and four Rajya Sabha elections, and has been minister in National Front, United Front and NDA cabinets. But, he has not gathered strong political mass like fellow Yadavs—Lalu and Mulayam. Yet, he is an important figure, with acceptance across the spectrum of backward castes and dalits, and their leaders in north India. His followers say that he lacks the extreme ambition and ruthlessness needed to float and run a regional party.

Though there are heavyweights with strong regional bases who are negotiating for the grand opposition unity, Yadav’s lack of a political base itself holds special attraction for the Congress. While regional chieftains like Sharad Pawar and N. Chandrababu Naidu are speaking to parties which are likely to oppose Narendra Modi in May, it is Yadav who can be a trusted go-between in the Hindi heartland. His connection spreads from large players to small chieftains like Chotubhai Vasava of Gujarat to Om Prakash Chautala in Haryana to Upendra Kushwaha of Bihar’s Rashtriya Lok Samta party. Yadav also has a rapport with communist leaders, as he has known generations of left leaders. He had never thought seriously of his state-level chances, preferred to operate as a senior leader in Delhi and was a key figure in Janata Dal (United) until he fell out with Nitish Kumar over the party returning to the NDA. What gave relevance to Yadav in opposition politics was the intensity of Nitish Kumar’s revenge to deprive Yadav of his Rajya Sabha seat, which has been challenged by Yadav in the courts. Rahul Gandhi was particularly impressed that Yadav sacrificed his political positions to stand with the Congress-Rashtriya Janata Dal coalition.

The Congress has a lot riding on the current round of assembly elections. If it makes a mark in the elections, then its attention turns to stitching a stronger caste alliance in the Hindi heartland. Yadav was part of the AJGAR (Ahir, Jat, Gujjar and Rajput) coalition cobbled by V.P. Singh, Devi Lal and Chandrashekhar against the Congress in 1989. He later helped the BJP broaden its social base, because of the alliance against Lalu Prasad in Bihar with Samta Party, which later merged with Janata Dal (United). The stalwart is unconcerned that he is now working at stitching a social coalition around the Congress to take on the BJP. For him, the political wheel has had many turns.

sachi@theweek.in