Carmaker Toyota recently had a promotional event at Lasalgaon, a sleepy town with a population of around 20,000 in Nashik, Maharashtra. “The company was pleasantly surprised to receive cash payments for 70 sports utility vehicles in eight hours,” said Girdhar Patil, an activist. “Most of the buyers were traders in the local agriculture produce market committee.”

Lasalgaon has the biggest agriculture produce market committee (APMC) in Asia, with onion as the biggest selling commodity. The town, however, does not have good roads, hospitals or schools. Even the APMC does not provide the basic infrastructure to the farmers, not even the storage facility to stock their produce. The farmer brings his produce on hired tractors, pays an entry fee to get inside the APMC, pays for the weighing while unloading his produce and pays again for the weighing when he sells them.

In contrast, the trader, who comes in a swanky car or SUV, does not have to pay the entry fee. He places his bids in the auctions and the staff ensure the delivery of the produce at his warehouse. “The staff give us handwritten slips for the quantity he has bought from us. We are asked to come after 8-10 days to collect the payment,” said Bhivaji Bhavle, a vegetable farmer from Pimpalgaon Bahula in Nashik. “Almost 80 per cent of the business is in cash. We get 70-75 per cent of the amount written on the slip―10 per cent is deducted for the gradation of the produce, 8-10 per cent for weighing, loading and unloading, and 7 per cent is the commission. We receive Rs3,600 if the slip is for Rs5,000.”

Shrikant Ghatge | Amey Mansabdar

Shrikant Ghatge | Amey Mansabdar

The payment in cash ensures that no records of the transaction are created. Bhavle said the entire business of vegetables, fruits, grains, corn, onion and potato is done only in cash. This is in violation of the Maharashtra Agricultural Produce Marketing (development & regulation) Act, 1963, which does not allow cash or deferred payment. “It is mandatory to make payments within 24 hours of the trade. But no APMC has ever punished a single trader for this,” said Patil. It is mandatory under the APMC Act to sell agro produces only in APMCs at least at the minimum support prices (MSP) announced by the government.

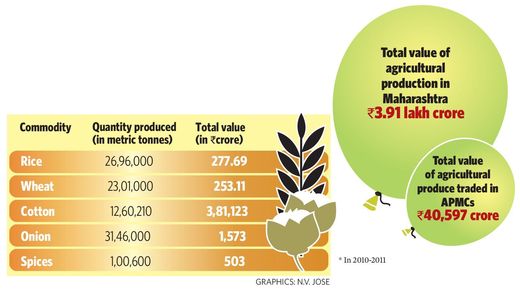

The Economic Survey of Maharashtra mentions the total production of every single crop produced in the state. “The total value of the agricultural produce in Maharashtra is calculated by multiplying the quantity of each produce by its respective MSP and then by summing the values of all the produce,” said Patil. For instance, in 2010-11, as much as 23.01 lakh metric tonnes wheat was produced in the state and the MSP in that year was Rs1,100 a quintal. This shows that the total wheat production in Maharashtra during 2010-11 was worth Rs 253.11 crore. Cotton production was worth Rs3,81,123 crore, the highest valued in the state. “If the values of all these agricultural commodities are added accordingly, the total agricultural production in Maharashtra during the year 2010-11 was Rs3,91,132.446 crore,” said Patil.

The report, however, says the total amount of trading in 305 APMCs in the state is only Rs40,596.86 crore. “This is atrocious,” said Patil. “It means that only 10 per cent of the agricultural produce is getting sold on record. Just imagine the kind of business that is done in cash and the proportion of tax evasion. It also means that most of the trade is happening below the MSP.”

Shrinivas Jadhav, secretary to the cooperatives minister Chandrakant Patil, said many commodities were sold directly to traders and hence those amounts did not appear in APMCs’ turnover. “About 90 per cent of the cotton gets sold directly to the traders in open market. Similarly, soybean, grapes and mangoes are sold directly to traders without any involvement of the APMCs,” he said. “We have given licences to 65 traders to purchase directly from farmers, and institutions like Maharashtra State Warehousing Corporation even provide online selling and buying facility for crops like soybean.”

Patil said it was an admission of the government’s apathy towards farmers. “How can a government say that these businesses take place directly with traders without APMCs’ involvement when it is the legal responsibility of the government to ensure that every single agricultural commodity is sold only through APMCs,” he said.

There is an argument that the commodities that are locally consumed and sold in the local markets are not shown in the APMCs’ turnover. But Patil refuted it. “Most of the monsoon-dependent and marginal farmers produce cash crops like onion, rice, cotton and soybean. These cannot be entirely consumed locally,” he said. “And, the percentage of business that happens in the weekly markets in rural areas is extremely low.”

The Kolhapur APMC has better roads than the one at Lasalgaon. Jaggery is the main commodity traded here. The bidding is conducted for a 100kg column of jaggery blocks weighing 10 or 25kg each. Everything appears fair and square until you speak to a farmer. “A 10kg block weighed by us weighs only 9.8kg on traders’ scale. It comes down further after tasting by some 20 taste experts, and the payment finally is done for only 9kg,” said Shrikant Ghatge, a farmer and leader of the Swabhimani Shetkari Sanghatana.

The APMC officials stop the auctioning if the farmers object. “A farmer cannot take his produce all the way back and he doesn’t get storage space in the APMC,” said Bhagwan Kate, president of the Kolhapur district Swabhimani Shetkari Sanghatana. “He simply succumbs to the pressure tactics.”

The farmers are exploited at different levels. “The payments are always made in cash and in a deferred manner,” said Ghatge. “If a farmer is in dire need, the trader would lend him some money. He deducts the interest while making the rest of the payment. It takes nearly two months for the full payment.”

For fenugreek and green vegetables, auctions are held for 117 bundles while payment is made for only 100. “Seventeen bundles are taken towards possible losses during transportation,” said Ghatge.

Kolhapur had 1,200 jaggery making units a few years ago; now there are only about 400. “Farmers are disheartened. But we don’t have many options; whatever we produce we have to surrender to the unjust practices, and nobody listens to our grievances,” said Kate. Kolhapur APMC’s secretary Sampat Patil was not available for comment.

Pasha Patel, farmer and former member of the legislative council, is in possession of a report that the Union government had submitted to the World Trade Organisation in the late 1990s. The report shows the difference between the prices that farmers get and those the consumers pay in the open retail market. “The total money that all farmers got [at that time] in India for rice was Rs48,380 crore while it was sold at Rs75,773 crore to consumers. For wheat, farmers got Rs26,322 crore while consumers paid Rs64,919 crore,” he said. “And if most of this business is happening in cash, I shudder to imagine the tax revenue that the government has lost in all these years.”