Seven decades. Two countries. One hundred and sixty-two enclaves. More than 51,000 residents—midnight's children, but with a difference.

On August 1, more than 14,000 people living in 51 Bangladeshi enclaves in India breathed freedom at last, thanks to the implementation of the long-overdue land boundary agreement between the two countries. From “unregistered Bangladeshis”, they have now become citizens of India. “It was India that created a Bangladesh nation. Bangladesh should recognise it. India is a great nation and ultimately gave up more land to Bangladesh in this agreement out of sympathy. So we want to be Indians,” said Monsur Ali Mian, 80, a resident of Poaturkuthi enclave in West Bengal. “I am happy that I could see this happen at least in my lifetime. Many thanks to Narendra Modi.”

However, the fates of more than 37,000 people residing in 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh are still hanging in the balance. About 1,000 settlers in these enclaves wish to return to India but are reportedly unable to cross over because of local resistance. This despite the fact that the agreement gives the residents of the 162 enclaves the choice of citizenship. A joint coordination committee is currently in Bangladesh to ascertain the number of people who wish to cross over. “As of now those who want to come over to India should be given a chance to do so,” said Diptiman Sengupta, member of the coordination committee.

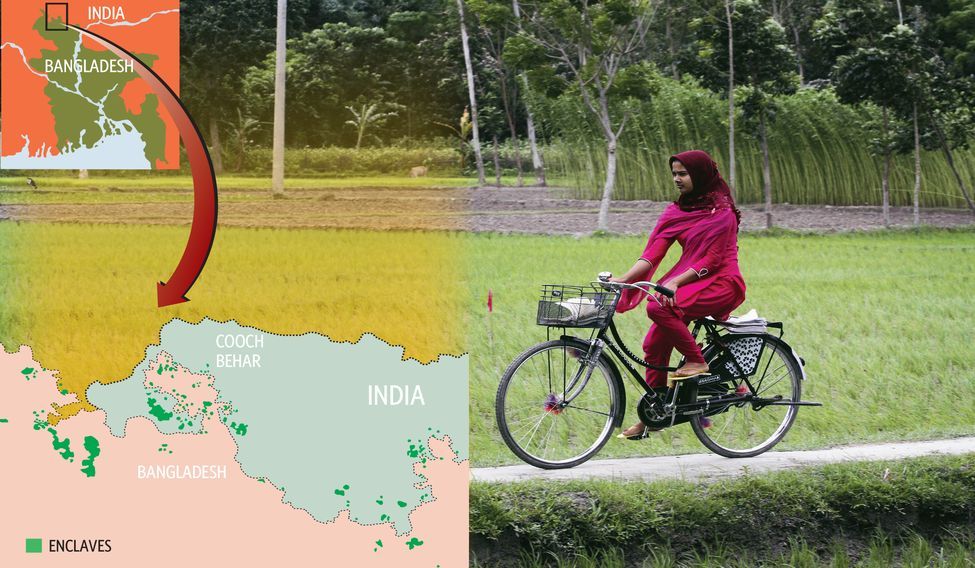

The boundary dispute between India and Bangladesh was centuries old. Legend has it that the kings of Cooch Behar and Rangpur used land as stakes during shatranj (Indian chess) competitions. Since the Cooch Behar king had more wins than the Rangpur king, he is said to have won 17,161 acres in the latter's territory. The Rangpur king, on the other hand, won a little more than 7,000 acres in his opponent’s territory in one district. But there are also reports that the enclaves came into existence thanks to a treaty between local rulers and the Mughal empire in 1713.

While drawing the boundary line between India and Pakistan post partition, Cyril Radcliffe, chairman of the boundary commission, too, did not address the issue of enclaves, calling it a minor dispute that the countries could settle on their own. So, Cooch Behar stayed with India and Rangpur became part of what was East Pakistan. After the formation of Bangladesh in 1971, the two countries tried to resolve the boundary dispute time and again (see box). But it was only in 2011 that the land boundary agreement got a power push, thanks to prime minister Manmohan Singh.

Singh first spoke to Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina about the boundary issue in 2010 and followed it up with a visit in 2011. India agreed to part with its enclaves spread over 17,161 acres in Bangladesh. Instead, the Bangladeshi enclaves covering about 7,000 acres would become part of India. Hasina did her job at home by persuading political parties to accept the land agreement as she was in a win-win situation.

But back home, Singh faced huge resistance from West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, who said Bengal would not lose any land to Bangladesh. A former UPA minister from Bengal, however, said that Singh engaged former national security adviser Shiv Shankar Menon to discuss the issue with Mamata. “Menon went to Kolkata several times and tried to convince her that giving up the land, which is in a remote area, was not a big deal for the state,” he said.

Singh, however, gave up when Menon’s talks with Mamata were inconclusive. But Prime Minister Narendra Modi took over from where Singh had left. He got External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj to do the talking, got the Constitution amended and even persuaded Mamata to travel to Bangladesh with him in June, when the agreement was finally ratified. But he had local help, too. Residents of the enclaves in Bengal erupted in protest, no longer willing to put up with hardship in the no man’s land with no electricity, school or any basic health care facility. THE WEEK, in its October 2, 2011 issue, portrayed how polio vaccination programmes of the United Nations could not be initiated in the 51 enclaves in India. Also, atrocities against women were common here, but the law turned a blind eye to them.

With the land agreement in effect, India can no longer neglect these enclaves. It will have to start from scratch. The chief minister has already demanded a few thousand crores from the Centre to create basic infrastructure in these areas. For the Indian government, one of the prime issues would be to give voting rights to the enclave dwellers. P. Ulaganathan, Cooch Behar district collector, said that he had asked the Election Commission to enrol them in the voters list so that they could vote in the assembly polls next year. But an Election Commission official in Kolkata said, “We are yet to receive the details of the agreement and how these people have been given citizenship. The action will follow after that.”

But on the other side of the border, Hasina is trying hard to check the exodus of enclave dwellers to India. Sources said Hasina has assured them that the new Bangladeshis, including minority Hindus, would be taken care of like ordinary Bangladeshis elsewhere. “But then too, the country is too poor,” said Monsur. “Why should one have to stay there? They have faced more troubles than we have faced here.”