March 8 was a night to remember.

The who’s who of Indian cricket had gathered at The Ritz-Carlton Hotel in Bengaluru for the BCCI Annual Awards. On the podium, delivering the fifth M.A.K. Pataudi Memorial Lecture before the ceremony, was the inimitable Farokh Engineer. The 89-year-old, effervescent as ever, recounted how he used to get only Rs50 a day—Rs250 a Test—when he played for India.

“Did you hear that, Virat?” he asked Kohli playfully. The Team India skipper, who was seated close to the dais, playfully wiped his brows and let out a laugh. The audience laughed along.

Not long after Farokh stepped down, Shantha Rangaswamy came on stage. The 63-year-old, considered the matriarch of women’s cricket in India, was bestowed the BCCI’s lifetime achievement award, four decades after she had led India to its first Test victory.

The award came with a cheque for Rs25 lakh, but it wasn’t about the money. What mattered was that it was the first-ever such honour that the BCCI had instituted for women cricketers, more than a decade after it began running the women’s game.

In her emotional speech, Shantha described herself as one of the “founding mothers”, a rather motley group whose exploits fostered women’s cricket in India. She also took a gentle dig at Farokh. “Yes, Farokh was talking about how passionate the game was to them, and that they were paid Rs250 a day. Well, that was a fortune for us, because till date I have never been paid,” she said. “We travelled by unreserved second class, stayed in dormitories, played on rough wickets…. All that, I think, is a thing of the past.”

It is, indeed.

Diana Edulji with teammate Anjali Pendharkar | Mid-day Infomedia

Diana Edulji with teammate Anjali Pendharkar | Mid-day Infomedia

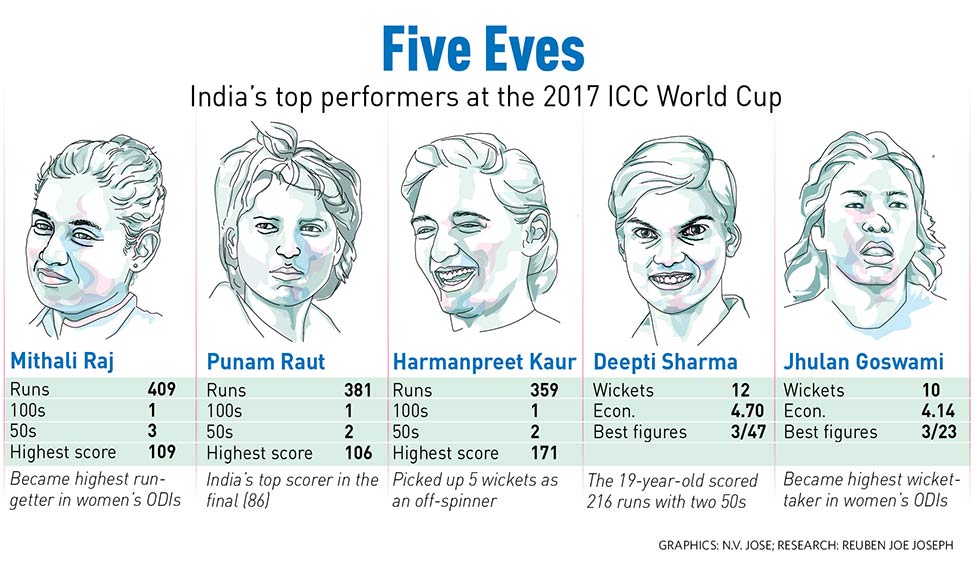

The proof is the rousing reception the current crop of Team India players received as they landed at the Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport in Mumbai in the early hours of July 26. Led by Mithali Raj, the players had done India proud by reaching the final of the ICC Women’s World Cup in England. They did lose the final against England at Lord’s, but not the hearts they had won with their memorable campaign. “It is just the beginning of good times for women’s cricket,” said Mithali.

That beginning, as Shantha would tell you, was more than four decades in the making.

BORN IN BENGALURU in 1954, Shantha was one among seven sisters in the Rangaswamy household. Her father, the lone male in the family, died when she was 12, and it was her mother who took care of them.

Shantha grew up playing tennis-ball cricket in the backyard of their large family home. She took to cricket like fish to water, and was so good at it that she was selected for the first national tournament in Pune in April 1973.

That tournament later became famous for the number of participating teams—two and a half, exactly. “Mumbai, Maharashtra and half of the Uttar Pradesh side!” recalled Shantha. “All extra players then played for UP, including the likes of future India captain Nilima Jogalekar. Seven months later, there was a second nationals in November. Seventeen teams took part in it. After that, the WCAI was formed.”

Meeting of generations: (From left) Jhulan Goswami, Shantha Rangaswamy and Diana Edulji | Courtesy: Xtra Time

Meeting of generations: (From left) Jhulan Goswami, Shantha Rangaswamy and Diana Edulji | Courtesy: Xtra Time

The Women’s Cricket Association of India (WCAI) was the brainchild of a gentleman. Mahindra Kumar Sharma, a sports enthusiast from Lucknow, saw the budding interest in cricket among girls. He registered WCAI in 1973, under the Societies Act in Lucknow. Later, it was also affiliated to the International Women’s Cricket Council.

Three years after WCAI came into being, women cricketers made their Test debut against the visiting West Indies, and recorded their first win in the six-match series. With 381 runs, Shantha was the topscorer in the series. The same year, she won the Arjuna Award. Under her able leadership, the girls had clearly set the ball rolling. “As pioneers, we laid a solid foundation [for women’s cricket], which would have died out but for us,” said Shantha.

In 1978, three years after the men’s team had made their World Cup debut, India hosted and debuted in the second edition of the Women’s World Cup. Shubhangi Kulkarni, who was 17 when she made her Test debut, vividly remembers those times. “When I started playing cricket, a year before it formally began in India, the girls were simply playing it for the love of the game,” she said. “We had no role models. All that people wanted to know was whether the girls were playing in shirts and trousers, or skirts.”

Shubhangi, who went on to become captain, remembers India’s first Test match against Australia at home—in Delhi in January 1984. “A lot of people came to see out of curiosity,” she said. “They saw some good batting and bowling. People started talking about the girls.” In the first innings, Shubhangi top-scored with 42 runs. The match was drawn, as was the four-match series.

Shantha was succeeded as skipper by Diana Edulji, whose sister Behroze had been in the team that made its Test debut against the West Indies. Both Diana and Behroze had played for the Albees, Mumbai’s first women’s cricket club, which had it nets sessions on Wednesday and Saturday evenings at the Cricket Club of India. Albees had the backing of veterans like Vijay Merchant and Polly Umrigar.

“We started out in 1974,” said Diana. “None of us had jobs. We travelled in unreserved compartments and by bus. I remember going from Mumbai to Patiala by bus; those were very rough days.” More often than not, the players themselves had to pay for the trips.

Almost there: India’s Rajeshwari Gayakwad tries to run out England’s Jenny Gunn in the 2017 World Cup final at Lord’s | Reuters

Almost there: India’s Rajeshwari Gayakwad tries to run out England’s Jenny Gunn in the 2017 World Cup final at Lord’s | Reuters

Shantha remembers one incident in 1977-78, when the team was touring Australia and New Zealand. “We spent Christmas in Queenstown. We stayed with Indian and Kiwi families,” she said. “When we landed, we were taken to a home. The lady of the house asked us whether we wanted tea. I said, ‘No, thanks’, thinking that there will be dinner. But there was none. The following day at the ground, we asked our manager, “What is this!” And we were told that ‘tea’ is what they call dinner.”

WCAI had few funds or resources, but the girls did not let that stop them. “In 1982, we had to go for the World Cup in Australia and NewZealand,” remembers Diana. “We had to pay Rs10,000 from our own pockets. We didn’t have that kind of money. So we approached Maharashtra chief minister A.R. Antulay through the media. A sports editor did a front-page story that said three girls from Maharashtra would be unable to go, so the state must step in. Antulay came forward to help us.”

She soon got a job in the railways. Frustrated over the absence of any initiative to popularise women’s cricket, she requested Madhavrao Scindia, then railway minister, to take steps in this regard. “He agreed and formed five zonal teams; that was the only way girls could play and earn. Today, 10 of 15 girls who played in the [this year’s] World Cup are from the railways,” said Diana.

Players in the seventies and eighties could overcome the shortage of funds, but WCAI’s poor administration was something they could not rectify. “There was no international series from 1977 to 1984, nor from 1986 to 1991,” said Shantha. “That’s 11 to 12 years of our peak time—of Diana, me and our contemporaries.”

India missed the 1988 World Cup in Australia, because WCAI officials had a run-in with Union sports minister Margaret Alva. The team was denied permission to go to Australia. Diana and her teammates approached prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, who finally agreed to fund the team’s campaign. But, by then, the entry date had passed.

In domestic cricket, the playing conditions ranged from poor to abysmal. Diana remembers the 1984 national championship, in which the Indian Railways team participated for the first time. The venue was K.D. Singh Babu Stadium in Lucknow. “There were two rooms for two teams and a common toilet and open-air kitchen covered by a tarpaulin sheet. We had to use the same buckets for bathing and to go to the toilet,” said Diana.

The situation was grimmer at venues like the Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium in Delhi, where camps for the national women’s team were often held. “The food contractor would make substandard stuff,” said Diana. “[In Delhi] we would all go to the nearby Defence Colony market, because the thought of three meals at the Nehru Stadium was unbearable. We would train in the morning and the evening, and then wash our clothes at night. But we did all that because, first and foremost, we enjoyed playing.”

BY 1991, THE era of pioneers had almost ended. In the succeeding years, the likes of Purnima Rau, Anju Jain, Neetu David, Hemlata Kala, Jaya Sharma and Anjum Chopra arrived on the national scene. It was a transformative period, one that saw marked changes in technique and approach to the game.

It was by the turn of the century that women’s cricket in India really came of age. Mithali Raj, the current skipper, made her ODI debut in 1999, while her teammate Jhulan Goswami debuted three years later. Both the players now dominate international cricket in ways that few who grew up in the Shantha-Diana era could have imagined. Mithali is now the world’s highest run-scorer, while Goswami has the most number of wickets.

There has been sweeping changes in the administrative side, too. Shubhangi, the former skipper, took over as WCAI secretary in 2003. Her immediate challenge was to assemble a capable team for the 2005 World Cup in South Africa. “I felt our girls had the skills, but we lacked in preparation,” she said. “We were practising on small grounds. Our bowling was good, but our fielding was bad, as we couldn’t dive in our fields.”

There was a reason that the fielding was bad. An entire generation of cricketers had grown up playing in grounds that were little more than agricultural fields. The rough surfaces prohibited them from being too adventurous when it came to stopping the ball.

Shubhangi and her colleagues, however, were up to the challenge. “Sahara was roped in as the team sponsor,” she said. “Actor Mandira Bedi helped WCAI to negotiate the deal.”

WCAI then tied up with Infosys, which threw open its 350-acre campus in Mysuru for the team. “We talked to [Infosys chairman] Narayana Murthy and [board member] T.V. Mohandas Pai. They agreed to give us the facilities till the World Cup. We also got their in-house physical and mental trainers. Murthy and Pai even had sessions with the players on leadership and team-building. We could see the difference they made—the body language [of the players] changed; their confidence was up.”

More challenges, however, awaited the players in South Africa. “There, we had dorms to stay in,” said Jaya Sharma, a team member. “We were put up in the last two blocks. There was no fan or AC. The first two buildings were reserved for Australia, New Zealand and England. That gave us a jolt. We didn’t like it.”

The girls gave vent to their anger on the field. They performed so well that they reached the final for the first time. Though they lost to Australia, they proved their potential.

On the administrative side, the game-changer was, perhaps, the merger of WCAI and the BCCI in 2006, when Sharad Pawar was the latter’s chief. The BCCI had initially dragged its feet through it, but it was ultimately compelled to do it because of directions from the International Cricket Council.

The merger, however, was slow to bear fruit. Though players got access to better facilities and more funds, the number of matches came down drastically. It famously had Mithali saying that the players had more camps than matches.

Things, however, have finally taken a turn for the better. There are now more international matches, thanks to new ICC rules that stipulate that all countries must play against each other to qualify for the World Cup.

Also, with the Supreme Court-appointed committee of administrators now in charge of the BCCI, women’s cricket in India seems to be on strong footing. Diana is one of the members of the CoA, and she is said to have been instrumental in the BCCI’s decision to institute the lifetime achievement’s award for women cricketers.

Still, a lot remains to be done. Diana knows that there is an urgent need for building up bench strength. “There is no replacement right now for Mithali and Jhulan,” she said. “We need to do here what Rahul Dravid is doing for the boys.” As India A coach, Dravid has been busy moulding the next generation of male cricketers.

With her position in the upper echelons of the BCCI, Diana is determined to push ahead, as she had always been as a player. “I am used to fighting for everything,” she told THE WEEK. “You can’t be shy; you have to ask.”