These days, farmers spray eight or nine different pesticides on ladies' fingers to make them big and fat; if a person consumes even a bit of those pesticides, he would die on the spot. It's doped vegetables that we eat these days and you're talking of doped athletes,” said an elite Indian athlete, using the analogy to emphasise the extent of doping in Indian sports.

Doping in sports, especially in athletics, is in the news once again following a sensational exposé by The Sunday Times and German broadcaster ARD/WDR, which claimed to have secret data from an International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) whistleblower with access to 12,000 blood test records. The report said endurance runners with suspicious blood-test results had won a third of the medals in Olympics and world championships between 2001 and 2012. But, the IAAF failed to follow it up.

Another exposé, a documentary called Top secret doping: How Russia makes its winners, said nearly all Russian athletes resorted to doping and it was “made to disappear with the alleged help of Russian anti-doping officials.” This is bad news for India, too, as Russia has been a favourite training base for many Indian athletes.

Even more worrying for India is the news that the leaked report referred to blood samples of 70 Indian athletes. The allegations have come at a time when the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) released its anti-doping rule violations (ADRV) report for 2013. India was ranked third in the list of ADRVs after Russia and Turkey.

Crime and punishment: Sini Jose and Tiana Mary Thomas at the National Dope Testing Laboratory, Delhi | PTI

Crime and punishment: Sini Jose and Tiana Mary Thomas at the National Dope Testing Laboratory, Delhi | PTI

Ajit Sharan, secretary in the Union ministry for sports and youth affairs, and vice chairman of the National Dope Testing Laboratory, Delhi, said no Indian cases were part of the leaked data. “We have checked with the National Anti-doping Agency (NADA) and it said there were no Indian athletes involved in violations of blood samples,” he said. There are, however, doubts whether NADA has access to data before 2009.

WADA has now introduced the Athletes' Biological Passport (ABP) programme wherein blood samples of athletes are collected and tested over a period of time to detect the use of human growth hormones like erythroprotien, synthetic oxygen carriers and blood transfusions. These techniques and substances allow the body to transport more oxygen to the muscles and thereby increase stamina and performance.

Of the 95 confirmed violations by Indians listed in the WADA report, 30 were from athletics, followed by 19 from weightlifting. The Athletics Federation of India (AFI), however, prefers to believe that doping is rampant only at the lower levels and its elite programme is clean. “Most of the negative cases are at the junior/youth level, of those making transition from junior to senior level. Apparently, what is getting them into this is the desire to win at all costs. There are so many incentives for athletes given by states, which is a good thing, but the issue here is of taking shortcuts to success,” said Sharan. He said some of the negative results could also be caused by the athletes consuming “contaminated” supplements bought off the shelf from local chemists.

Ben Nichols, WADA's senior manager for media relations and communications, said the fact that doping athletes were being detected through NADA's anti-doping programme was good news for clean athletes. “It shows that the programme is effective in detecting doping.” He, however, said WADA had some concerns with certain aspects of the Indian anti-doping programme. “Our role is to scrutinise anti-doping programmes worldwide, and as such we reviewed NADA’s testing and results management structures, including the provision of appeals processes, to ensure that cases are dealt with in a more timely and expedited fashion,” he said. WADA has offered NADA assistance from the Australian Sports Anti-doping Authority (ASADA). A NADA team led by senior project officer Dr Saravana Perumal S. will be meeting ASADA officials soon.

Another ambitious initiative of NADA is to set up a whereabouts Registered Testing Pool (RTP) for athletes. After many delays, it was launched in July, with barely a year to go for the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. This is a registered pool of top athletes, who are tested out of competition, without advance notice, based on their location information filled in a computer system. The first pool of 40 athletes is exclusively from athletics. The delay in setting up the pool, according to NADA and the AFI, had a lot to do with the athletes’ lack of access to and understanding of the system software.

NADA plans to gradually enlarge its whereabouts pool to cover weightlifting, boxing, wrestling and other disciplines. However, even with the RTP, the timing of the tests is crucial. Top Indian athletes have always managed to allegedly evade out of competition testing. There have been several instances—at Potchefstroom in South Africa in 2006, Ukraine in 2010 and at the National Institute of Sports, Patiala, and Sports Authority of India's training centre in Thiruvananthapuram several times—of athletes going missing as IAAF teams arrived for testing. The news of over 30 Indian athletes running with their bag and baggage through the streets of Potchefstroom to evade testing even made international headlines.

Often, the athletes lined up before international anti-doping teams are the ones the coaches are sure will pass muster. Besides, top athletes are said to skip events to evade testing. Quarter milers Ashwini Akkunji and Juana Murmu, discus thrower Krishna Poonia and triple jumper Renjith Maheshwary skipped the Federation Cup athletics held in Mangaluru in April-May. The AFI, however, said these athletes missed the meet because of injury.

In April and May, there were reports about seven athletes going missing from a SAI training camp in Thiruvananthapuram. While two of them surfaced later at NIS Patiala, the rest were said to be “on leave”. As per WADA rules, if an athlete goes missing, it is considered to be an offence, especially after having reported his or her whereabouts to the IAAF for testing. A ban for up to four years can be imposed after three warnings. No such case, however, has been reported so far as attendance registers in SAI centres always show the missing athletes to be on leave for medical or personal reasons.

AFI secretary and former Olympian C.K. Valson denied that any of their top athletes had missed or evaded tests. “Someone is spreading canards. NADA knows each athlete by photograph. If they were not there, why didn’t NADA take action,” he said.

Those who were caught for doping, too, seem to be rehabilitated without proper scrutiny. Some of the members of the 4x400m women's relay team, which is considered to be among the top medal prospects for India in the 2016 Olympics, belong to this category. Akkunji, who served a ban after testing positive for anabolic steroids in 2011, made a return to the relay team without competing in any major event. Valson said Akkunji had been suffering from an injury sustained at a coaching camp. “We cannot throw an athlete out because of an injury. We have to ensure that athletes are looked after properly and given proper treatment.”

Akkunji's teammate Sini Jose, who also made a return from a ban, has not participated in any top meets, especially in the last one year. Her first major meet was the inter-state championships held in Chennai in July, where she crashed out in the preliminary round itself. Another quarter miler, Priyanka Panwar, too, has made a controversial return to the national squad. Panwar, who returned from a ban in 2013, was part of the gold-medal winning squad in the Incheon Asian Games last year. But she, too, has not run a single 400m race this year and her timings during the trials have been far from satisfactory. Yet, Akkunji, Jose and Panwar have found a place in the sports ministry's TOP (Target Olympic Podium) scheme for elite athletes. While a section felt that the entire system was against the “old relay girls” because they were “confident girls”, others said upcoming youngsters like P.T. Usha's protegee Jisna Mathew showed more promise. The women's 4x400m relay team finished last in an eight-team heats in the world athletic championship in Beijing last week.

Newly elected IAAF president Sebastian Coe (in pic) said what was unfolding was a media war on athletics.

Newly elected IAAF president Sebastian Coe (in pic) said what was unfolding was a media war on athletics.

The AFI has also brought back Ukrainian coach Yuri Ogorodnik to train the quarter milers. His service was terminated four years ago following a doping scandal.

Even more befuddling was the case of an identity switch that took place after the men's 4x100m relay team trials for the Asian Athletics Championships in Bengaluru in May. Manikandan Arumugam, who ran the anchor leg, helped the Indian team meet the qualification standards. But when the results were announced, the name of another athlete, Praveen Muthukumaran, appeared in Arumugam's place. The AFI refused to act although journalists present at the venue presented photographic evidence to prove the switch. Was the switch just a ploy to meet the qualification standards? Or was there another reason behind it? The shadow of doping refuses to leave athletics.

The scandals have put Indian and global administrators in a tight spot. Newly elected IAAF president Sebastian Coe said what was unfolding was a media war on athletics. “It is a declaration of war on my sport,” he said. “There is nothing in our history of sports of competence and integrity in drug testing that warrants this kind of attack.”

Cheat sheet

An Indian athlete, who is a multiple international medal winner, spoke to THE WEEK about how doping worked in India

When we first started competing at the school level, we would often see injections being given to athletes by coaches and we were told that these would help in getting good results. No one comes into athletics from the Ambani family. We compete because if we do well, we will get a job. Therefore, if someone gives something, athletes are always ready to take it.

During our junior days, coaches never told us about dope's side effects, but others would tell us that our voice would turn hoarse, there would be unnatural hair growth and we might develop serious diseases like cancer. But most of us would say that we would worry about it when we got cancer.

During my junior time, there was no dope testing like the way it is being done now. Now you do have multiple tests—random, in competition, out of competition—but athletes still take dope.

It is not that the coach would give you one odd tablet and you would perform well in your event. It is a proper one-month or two-month cycle. There is a chart which would tell you when to take each tablet and at what intervals. We were asked to stop taking the drugs 21 to 25 days before the event and drink lots of water so that no traces of these illegal substances were left in the body. We have never gone through the anti-doping list given by NADA or WADA, but the coaches would tell us what was banned.

Earlier in the camps, doping used to happen openly. Federations would call doctors and special injections would be given to the select few. Now, it is not so open. The programme has become more sophisticated. There are two programmes, one for the top athletes and another for the second-string athletes. Sometimes, you would pay from your own pocket, sometimes the federation or the coach would pay for it. A three-month, first-rate doping programme would cost Rs.3 lakh to Rs.3.5 lakh.

When WADA people would come, news would spread and certain athletes would be asked to leave the camp. The attendance register at the national camp would show them being on leave from a day before the team landed.

As told to Neeru Bhatia

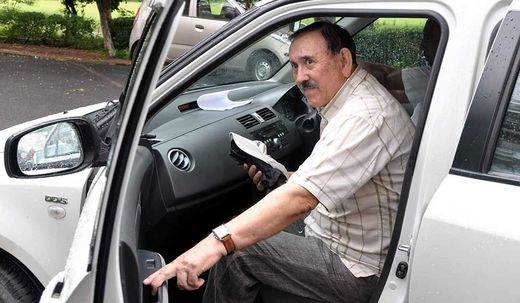

Strategic move: Yuri Ogorodnik at NIS, Patiala

Strategic move: Yuri Ogorodnik at NIS, Patiala

Coach class

By Neeru Bhatia

Yuri Ogorodnik's association with Indian athletics has been long and controversial. The 77-year-old Ukrainian coach is back after a four-year break. His contract with the Indian team was terminated after eight athletes who trained under him failed an anti-doping test conducted by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) and were subsequently banned.

It took the Athletics Federation of India (AFI) six months to persuade Yuri to return. The move came after the sports ministry and the Sports Authority of India okayed his appointment. The permission came after the AFI agreed to the conditions that Yuri would undergo stringent medical tests in Ukraine and that the association would foot the coach's medical bills. The ministry also wanted the coach to take responsibility for any possible doping cases in the future, although the AFI rejected this demand.

The soft-spoken Yuri, who earlier coached the women's 400m, 400m hurdles and 4x400m relay team, was accused of providing athletes supplements that contained banned substances. Ashwini Akkunji, Mandeep Kaur, Sini Jose, Juana Murmu, Priyanka Panwar and Tiana Mary Thomas had tested positive for anabolic steroids following this.

The AFI, however, decided to recall the coach to prepare the Indian quarter milers for the Rio Olympics. “The time for the next Olympics is very short. If we bring another coach now, it won't be possible to win a medal,” said AFI secretary C.K. Valson. Subsequently, the AFI convinced SAI that Yuri “could make a big difference to the athletes”. Moreover, there was no concrete evidence about Yuri's involvement in the doping scandal even after two inquiry committees probed the issue.

“We were told that the athletes and the AFI were very keen on Yuri, and at this stage, it would be very difficult to find a coach who could fill the gap to their satisfaction,” said Ajit Sharan, secretary in the Union ministry for sports and youth affairs. “Also, in the past inquiries, there was nothing against him, so we had no option but to engage him.”