More than 190 countries. A proposed corpus of $100 billion. Commitments to change fuel dependency from carbon-centric to renewable. And, yet, the goal of containing global warming at two degrees celsius remains a distant dream.

From November 30 to December 11, global leaders will meet in Paris for the United Nations Climate Change Conference, or Conference of the Parties, in the hope that, at the end of the deliberations, the world can come to a consensus on how to ensure global temperatures do not rise more than two degrees celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Doomsayers bleakly predict that even if the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDC), which more than 80 countries have submitted, are implemented, it may be too little too late. Temperatures will still rise by 2.7 to three degrees celsius. On the bright side, however, is the view that this is still a progress on the five-degree celsius rise that may happen, given the current trajectory of emissions. It is necessary to keep temperature rise within two degrees celsius, else the catastrophe will be difficult to reverse. A two-degree temperature change may seem insignificant, but, in climactic terms, its repercussions are massive. It is enough to sink several islands and ravage coastal cities.

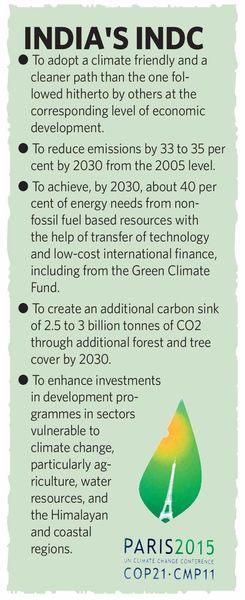

India’s role in this summit is an important and crucial one. As the third largest carbon-emitting nation after China and the US, its commitments to cut emissions are vital. However, India is also a representative of those nations whose development has only now begun and, for whom, emission cut has to be balanced with growth. So, its voice in negotiating differential responsibilities is vital.

Developing nations argue that while first world nations have already polluted the world and reached the present day comfort levels, the developing world has a long way to go. It is rather unfair that they be denied the chance to develop. They demand that green technology be made available to them to help them leapfrog the polluting phases of development. The western world, however, doesn’t show enough commitment for subsidised tech transfer. The developing nations also demand that the western world pay more to stem climate change.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s joint statement in April with French President Francois Hollande—about cooperating to fight climate change and working to reach a global climate agreement in Paris—is viewed as testimony of India’s negotiating role this December. “India’s will be a big voice in Paris,” said Jyoti Parikh, executive director of Integrated Research and Action for Development, a think tank which did background work for India’s INDC. Reports suggest that Modi may attend the meet.

India took time, submitting its INDC only on October 2. But, it has scored brownie points with a commitment that is strong on renewables (the target is to make renewable energy 40 per cent of its primary energy consumption). Also, India has linked its INDC with existing development projects such as Green India Mission. China, for instance, expresses a commitment to increase forest stock by 4.5 billion cubic metres by 2025, but does not elaborate how. India gives specifics—it will develop a 1.4 lakh km tree-line on both sides of national highways.

The meet in Copenhagen in 2009 ended without a binding and legal treaty. The expectations from Paris are higher. “Unfortunately, the bigger polluters are not committing enough to curb climate change. They have to be made to shoulder greater responsibility,” said Srikanta Panigrahi, director-general of Carbon Minus India, a carbon finance research organisation, and member of Modi’s climate change missions. “The US, as the largest per capita emitter, should have committed more than the 20 to 28 per cent emission cut by 2030.” The US anyway has a poor track record with commitments on climate change. It famously refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol of 1997, which was a well-drafted, legally binding treaty to cut emissions. The document never got validity.

China has a more ambitious INDC, with a target of a 60 to 65 per cent emission cut by 2030. However, the roadmap is not clear. China also says its emissions will peak by 2030, before the decline starts. “It should have targeted for an earlier peak,” said Parikh.

While nations were given the freedom to design their own carbon reduction plans, the problem at Paris will be standardising these objectives. While the US has put 2005 as the base year for its targets, the European Union has used 1990. China says its emissions will peak by 2030, but does not quantify it.

Also, who will monitor the performance of individual countries on their self set goals, and how? And how will different nations contribute to the corpus that will be set up to fight climate change? Equal contributions will not be acceptable to poorer nations, while there is always the pitfall of the richer nations buying their way out of responsibilities with larger contributions.

It seems that unlike Copenhagen, this time there will be a ratified agreement. US President Barack Obama has already called climate change a national security threat. Chinese cities, meanwhile, are losing global investments because of poor air quality. The last two years have been the hottest on record, a reality that has shaken the entire world. “The best takeaway from Paris would be a treaty that uses the INDCs as a starting point and leaves room for future debates. There could be a review in 2018 to tighten the screws,’’ said Parikh.