Come monsoon, and it will be raining frogs. But tracking them is no easy task, says Dr Sanil George, a scientist at the Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology in Thiruvananthapuram. “Once we had a narrow escape from a rogue elephant while looking for frogs in the Mudumalai forest. Another time, we saw two tigers wrestling and gashing each other. It was quite scary,” he recalls. “On a monsoon evening, one of my colleagues got leech bites that were so bad that he had to be admitted in hospital.”

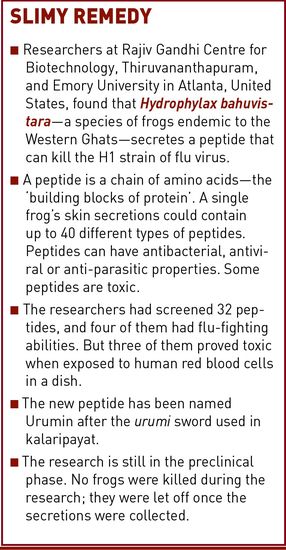

It was during one such trip to Kasaragod in Kerala in 2013 that George, 53, and his colleagues spotted the orange-striped Hydrophylax bahuvistara, a species of frog endemic to the Western Ghats. “It was hiding under a clay pot in a kitchen,” says George, who has pictures of this croaking species all over his workstation. During the course of their study, the researchers found that a peptide—a chain of amino acids—this frog secretes could kill the H1N1 virus. “Our study showed that the peptide isolated from this frog’s skin has antiviral property against the influenza virus and can be developed as a future therapeutic agent,” explains George.

The peptide has been named Urumin after a sword, urumi, used in kalaripayat, a popular martial art form of Kerala.

The study, done in collaboration with Emory University in Atlanta in the United States, offers hope to countries like India where drug-resistant swine flu virus has become a major health challenge. “The new peptide targets a different part of the influenza virus than the antivirals available in the market and is found to be effective even against drug-resistant H1 influenza viruses that currently circulate,” says Dr Joshy Jacob, associate professor at the Emory School of Medicine (department of microbiology and immunology), who was an investigator in the project. “Urumin destroys all the different strains of H1s.”

But, researchers had initially written off Urumin as it did not show any antibacterial activity in normal tests. The viral test results though showed promise, and the researchers explored it further.

Dr Sanil George | Benny Paul

Dr Sanil George | Benny Paul

Does Urumin have preventive potential, too? “Some of the studies we did in mice indicate that Urumin could protect them against the infection. However, that is not comprehensive evidence to show that it can act as a preventive or a vaccine,” says Prof M. Radhakrishna Pillai, head of Viral Disease Biology Programme at RGCB. “We are just done with our first round of studies in mice. Now we are going to look at whether the peptide works in other animals, which are naturally infected by the virus.”

Some of the frog skin peptides are toxic, like the ones secreted by some South American species—5ml of these peptides can kill 5,000 people, says George. “Fortunately, Urumin doesn’t seem to be toxic to human cells,” he says.

The study, published in the journal Immunity in April, has set the scientific world abuzz. RGCB, a national research centre, got into the study after the outbreak of swine flu in Kerala. “We set up a virology centre following requests from the Central and state governments,” says Pillai.

Urumin is able to annihilate H1N1 as Hydrophylax bahuvistara is genetically programmed to fight it for its own survival, says George. It gets exposed to pathogens, while living on land and in water, that share anatomical similarities with the virus. So the frog’s innate mechanism works when confronted with a similar attack.

Dr Joshy Jacob

Dr Joshy Jacob

The frog produces the peptide when confronted with a threat. To produce secretion, the frog was given mild electric shocks. “Once the secretion is collected, we let the frog out,” says George, who has been working towards enhancing conservation of amphibians. “We never kill frogs. After the sequence of the peptide is determined, we just chemically synthesise it. Then we don’t need the frogs anymore.”

The researchers use a technique based on molecular biology to identify the peptides. Each frog species produces a distinct peptide. The researchers have studied these peptides and identified the ones that can tackle other epidemics and pandemics, too. “These are very interesting preliminary studies. We have peptides that act against cholera bacteria and microbacterium TB. These were found in different species of frogs,” says Pillai.

The Western Ghats could hold the key to new treatments in future. The mountain range is home to the largest number of endemic frog species in the world. “More than 70 per cent of the frog species found in the Western Ghats are endemic,” says Pillai. “Peptides from these frogs offer endless possibilities for research. We have identified more than 100 peptides, some of which could combat even diseases that are hitherto untreatable.”