A few days after the death of Union minister Gopinath Munde in a road accident on June 3, 2014, his cabinet colleague in charge of transport and highways, Nitin Gadkari, announced the government's decision to replace the Motor Vehicles Act. He said the government would undertake a comprehensive revamp of India's road safety laws to ensure that those found guilty of violating traffic rules would not go unpunished.

In one of its last reports before it was disbanded, the Planning Commission of India had estimated the annual cost of road accidents in India to be at around 3 per cent of the country’s GDP. With the nominal GDP at Rs.126 lakh crore (2014-15), road accidents cost the country Rs.3.8 lakh crore last year, a figure that is eight times the budget of the ministry of road transport and highways.

Attempts to revamp traffic laws have been going on for more than a decade. In 2004, the Manmohan Singh government had appointed an expert committee headed by S. Sundar, former secretary of the ministry of surface transport, to look into the issue. Based on its recommendations, which was published in 2007, the transport ministry drafted the National Road Safety and Traffic Management Board Bill, 2010, for “development and regulation of road safety, traffic management system and safety standards in highway design and construction”.

The bill was presented in the Lok Sabha on May 4, 2010, by Kamal Nath, minister of road transport and highways, and was sent to the standing committee on transport, tourism and culture. Though the bill was referred back by the committee to the transport ministry for reconsideration, it was not resubmitted before Parliament. The Planning Commission had set up a National Transport Development Policy Committee in February 2010, under the chairmanship of its member Rakesh Mohan, to expedite the steps to formulate a long-term transport policy. The report of the committee was submitted in January 2014 to the prime minister, but no further action was taken.

After Munde's death, in September 2014 the transport ministry prepared a comprehensive draft of the Road Transport and Safety Bill (RTSB), which proposed stringent punishments, including a fine of up to Rs.3 lakh and a minimum of seven years imprisonment in case of death of a child in a road accident and fines and jail terms for vehicle companies for selling faulty vehicles. It also called for strong quality guidelines for vehicle manufacturers and their vendors for improving safety. The bill also called for abolishing regional transport offices. By the time the second draft of the bill was ready in January 2015, it found a lot of detractors.

Automakers, represented by the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM), were stridently opposed to many of the bill's provisions, including the mandatory recall of vehicles if 100 complaints were recorded. They were also against the proposed fine of Rs.5 lakh for faulty vehicles. The owner of the defective vehicle was also to be compensated by the manufacturer or get a replacement or repair. Vishnu Mathur, director-general of SIAM, said a complaint by 100 people should not trigger a recall, but should rather be a cause for an investigation or an analysis. He said the provisions of the draft bill were “arbitrary and unnecessary”. Following SIAM's opposition, the government released the third version of the bill with lowered safety guidelines. The third version, however, sought to overwrite the formation of an independent National Road Safety Authority to be the lead agency for road safety.

The move, however, led to opposition from states as they feared the Union government was encroaching upon a state subject. MPs from Tamil Nadu, Haryana and Bihar said their states would lose the right to collect road tax. “The states would continue to get their revenue from road taxes and would need to contribute only a small part of that for road safety,” said a transport ministry official, who had worked on the draft bill.

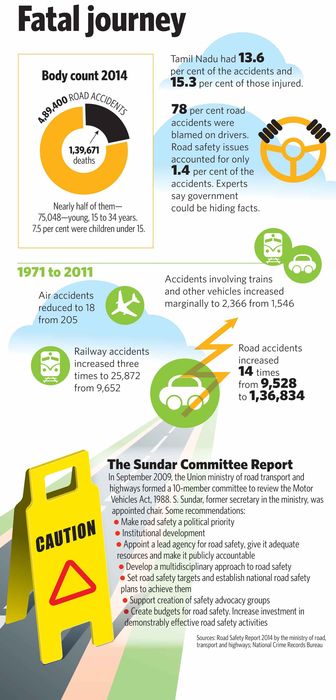

Graphics: N.V. Jose

Graphics: N.V. Jose

Gadkari said the bill would not encroach upon the rights of the state, but his ministry quickly published a highly watered down draft. The fourth draft reduced the proposed fines by almost one-fifth. In a major setback to accident victims and their families, the cap on insurance claims caused by death or disability in road accidents, which was raised to Rs.50 lakh in the earlier versions of the bill, was brought back down to Rs.15 lakh. The government also decided to keep with itself the power to appoint the head of the independent national authority in charge of road safety. Fine for overspeeding was reduced from Rs.15,000 to Rs.2,000 for the first offence; punishment for causing the death of a child reduced from seven years' imprisonment to one year; and the penalty for not complying with standards for road design, construction and maintenance was reduced from Rs.10 lakh per person killed to Rs.1 lakh. The three-year jail term proposed for contractors and engineers for causing death or injury because of faulty road construction was abolished.

Most of the remaining safety provisions were opposed by transporters' associations. They sought to remove the National Road Safety Authority’s power to rule on the size of vehicles and the permit licensing system. They also demanded that the power to issue permits for intra-state contract carriages should remain with state transport authorities.

The government buckled under pressure yet again and the state authorities retained the power to issue intra-state permits, while the national transport authority was given the power to issue interstate permits alone. On June 23, another version of the bill was published by the transport ministry. Experts said road safety definitions were further diluted. “Aspects of taking measures to reduce risk of accidents, driver education and protection of vulnerable road users have all been diluted this time,” said Piyush Tewari, chief executive officer, SaveLife Foundation, an NGO working on road safety awareness.

Tiwari said the government chose to further curtail the powers of the independent national body to oversee road safety. “It gives the Central government the power to supersede the national authority 'in public interest', compromising its independence. Detailed provisions regarding its regulatory powers, the functions of its chairperson and the appointment of technical groups were removed, compromising its transparency and accountability completely,” said Tiwari.

A unified driving licence system and a mechanism for detailed safety assessment tests were removed. Accident claims are also likely to suffer. “Most things necessary to set up an effective claims settlement mechanism have been either removed or pushed as rules to the act that would be notified later by the Central government,” said Tiwari. Offences related to drunk driving, using mobile phones while driving, over-speeding and violation of traffic signs, too, have been given a miss in the fifth version of the bill. An internal survey on road accidents conducted by the transport department has found that 89 per cent of road accidents are caused by driver errors. This is accentuated by the fact that Indian roads are not made with a scientific approach to safety.

Experts say good safety models are available within India itself. “We do not need to look abroad for good models. Look at Tamil Nadu, where the government has introduced computerised road accident recording and reporting mechanism,” said Arvind Kumar, a former senior adviser to the transport ministry. “The easiest would be to start with the national highways. Accident black spots on our national highways have been identified. All of these are caused by design faults. States like Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu have already demarcated them on Google maps,” said Kumar.

Kumar wants the Indian Roads Congress, the apex body of highway engineers, to act tough. “The IRC is yet to incorporate in its manuals aspects of road safety while biddings are announced. You cannot ask the concessionaire to do his own safety audit. Licence for contractors should be cancelled if a person is involved in causing more than two fatal accidents because of road design or maintenance fault,” said Kumar.

Krishna Dev, a former Planning Commission researcher who had worked on national road safety, said there were hardly any trained road safety professionals employed at the Central or state level. With more than five lakh commercial vehicles being added to the roads every year and training institutes capable of churning out just about one lakh drivers, there is an urgent need for more training facilities.

Gadkari has blamed “vested interests” for causing difficulties for his dream project. “The prime minister has advised wider consultations with all stakeholders on the road safety and transport bill and on the implications of it replacing the existing act,” he said. “The states are mainly opposing... We all know regional transport authorities are breeding grounds of corruption. The bill is to be placed in the cabinet soon and we hope to introduce it in the winter session of Parliament,” he said. Gadkari, however, conceded that not much could be done by him or his ministry alone. “Enforcement has to be strong to make roads safe. Everyone, the Centre and the states, should do it. No one should walk away from this responsibility.”

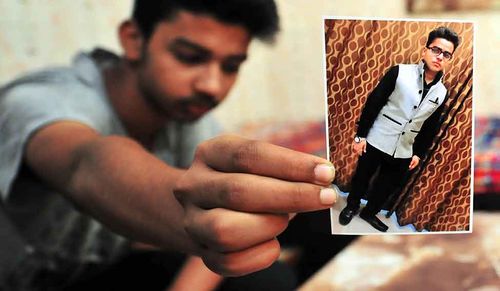

Eternity in an hour: Hit-and-run victim Vinay Jindal bled to death at a busy Delhi intersection | Aayush Goel

Eternity in an hour: Hit-and-run victim Vinay Jindal bled to death at a busy Delhi intersection | Aayush Goel

Enduring spirit

On the night of July 20, Vinay Jindal, 23, went out on his scooter to get medicines for his grandmother. Hours later, a police constable arrived at his home in Delhi's Dilshad Garden to inform the family that he had met with an accident.

Footage from CCTV cameras showed how Vinay’s scooter was mowed down by a speeding car at a busy intersection. The traffic light at the intersection had stopped working after peak hours.

As Vinay lay on the road bleeding, pedestrians and riders went past him. “The police took him to hospital about an hour after the accident. Had they taken my son a bit early, he might have been alive,” said Anita, Vinay’s widowed mother.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal took note of the accident. Modi spoke about it in his Mann ki Baat radio show. Kejriwal referred to the accident on FM radio slots. Yet, Vinay's family's search for justice continues.

Despite the CCTV footage, the police could not trace the killers. His family does not believe the police claim that they cannot read the number plates from the footage. Anita has written to Modi and the local MLA, seeking their help.

Demanding justice for Vinay, his friends took out candlelight marches. But, more importantly, they have pledged to make road safety a priority in their lives. “We will always stop if we see someone down on the road,” said Rahul, Vinay's cousin.

The police and the public works department have installed speed breakers and round-the-clock traffic lights at the accident spot. But Anita is inconsolable. “Maybe people should have shown courage and been a bit more sensitive before my child was gone,” she said.

Mother change: Doris regulating traffic at Kheda junction on NH 24 | Aayush Goel

Mother change: Doris regulating traffic at Kheda junction on NH 24 | Aayush Goel

Mom knows best

Kheda is a rundown village wedged between Noida and Ghaziabad on NH 24. It is the first gram panchayat on a border where a better managed Noida ends and Ghaziabad begins. This urban slum is home to about a lakh migrant workers who work in the cities nearby. In the absence of proper infrastructure, Kheda used to be an accident hotspot, especially in the early morning and late evening rush hours. Around 300 deaths used to be reported every year on the NH 24 stretch that runs through the place.

Fifty-eight-year old Doris Francis is a braveheart. Seven years ago, while travelling in an autorickshaw along with her husband and her ailing daughter Nikki, they were hit by a speeding car near the Kheda crossing. Nikki, who was seriously injured, died after struggling for nine months. Realising that the real killer at Kheda was its haphazard traffic system, Doris took it upon herself to regulate traffic in the busy streets. She is out at 7 in the morning with a lathi in her hands and a whistle on her lips. Dressed in a white salwar, she controls the careless drivers and the errant pedestrians. Her husband assists her. The Francis couple now manages the traffic with some help from the police.

“Doris Francis does a commendable job. The number of accidents at Kheda crossing has come down to zero,” said Kiran Yadav, superintendent of police, traffic, Ghaziabad. “I wish they had a proper traffic signal and pedestrian paths here,” said Doris. “I feel good that everyone can pass through here safely. This is my idea of love. It keeps me going.”

Mobility challenge: Komal Kamra at the crossing near Khalsa College, Delhi | Aayush Goel

Mobility challenge: Komal Kamra at the crossing near Khalsa College, Delhi | Aayush Goel

Hope springs eternal

As the number of vehicles on Indian roads has grown progressively, so have the number of accidents. Post-trauma care, however, remains far from adequate. “Post-trauma care training given to the police is haphazard at best. There is little awareness. In most countries, they are trained to pick up victims on hard neck-and-back support without causing much damage to their spines,” said Komal Kamra, professor of biotechnology at Delhi University’s Khalsa College.

Komal, who is a paraplegic, assists The Spinal Foundation, an NGO that works to rehabilitate those who are rendered disabled by road accidents. “The biggest cause of spinal injury in India is road accidents. I feel ashamed to share this at international conferences. Even in small Asian nations, they cite other reasons like adventure sports for spinal injuries,” said Komal.

Komal, too, is the victim of a road accident. Twenty years ago, while on a trip to Kashmir, the vehicle she was travelling in met with an accident. Two of her sisters and four other members of the family, including children, lost their lives. Komal and her mother escaped, but they suffered extensive spinal injuries. Since then, she has been working to increase awareness about road safety and disabled people.

“Disabled people are not a priority for anyone. People have big issues to fight on in Parliament, but the disability law is stuck for years,” said Komal. “Same is the fate of road safety laws.” When she met Union Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari at Transport Bhavan in Delhi, she told him how difficult it was for her to get into the building and the lift. “He promised to look into it,” said Komal.

Outside the Khalsa College campus, where Komal lives, she can make it to the bus stop only by staying off the pavement. Even negotiating a zebra crossing just outside her college in a wheelchair is impossible for her.

“Sensitisation is required at all levels. Government departments and organisations must work together, make timelines and meet them. The problem is that anything to do with traffic rules would need the Centre and the states to come together,” she said. But Komal is optimistic.

“It is possible. As a biologist I know that overcoming polio was a far more difficult challenge for us as a nation. If a metro railway system can be built, why can’t we do it with our roads? Only sensibilities of people need to change.”