As the Doklam crisis stares the Narendra Modi government in its face, the absence of a national security doctrine is telling in more ways than one. Several drafts have been made over the last many years, but none has been adopted. Today, there is no attempt to even formulate one.

In 1999, the National Security Advisory Board (NSAB), which reports to the prime minister through the security adviser, had prepared a draft nuclear doctrine—made public by then national security adviser Brajesh Mishra—in the midst of the Kargil war. It generated a healthy debate, and the doctrine, with a few changes, was formally adopted by the government in 2003.

Since then, the attempt had been to draft a national security strategy. A few drafts were made during the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. “When I was the NSA, we worked on it,” said M.K. Narayanan, who was Manmohan Singh’s security adviser during the first term. “There have been several drafts, but none was approved. That was probably because the government could not come to an understanding on what constitutes national security policy.”

Another draft was made by the 16-member NSAB, headed by former foreign secretary Shyam Saran, during the UPA’s second term when Shivshankar Menon was the NSA. The board made a presentation before Prime Minister Modi in September 2014. Saran used his bilingual (Hindi and English) skills, which gave a softness to a complex issue that needed the indulgence of his audience. During the hour-and-a-half audiovisual presentation, Modi asked several questions, particularly on the recommendations to set up a cyber command and space command. This discussion was the board’s swan song. Four months later, the members met Modi over a farewell lunch. The doctrine has since been gathering dust.

A new board was set up in 2016. Instead of 16 members, there are only four now—P.S. Raghavan, former ambassador to Russia, heads it, with former Research and Analysis Wing official A.B. Mathur, Lt General (retd) S.L. Narasimhan and Prof Bimal N. Patel of Gujarat National Law University as members.

The Saran-headed board had wanted their draft doctrine, a 45-page document accessed by THE WEEK, to be put up in the public domain to generate discussion and debate. But, nothing has happened. “We made the presentation to the political leadership, but it is for the leadership to decide upon implementing the recommendations we made,” said Saran. THE WEEK got in touch with the office of National Security Adviser Ajit Doval to seek his response, but Doval gently excused himself.

The decision-making today, pointed out a former NSAB member, is largely ad hoc. “When something happens in Doklam, we react to that. When something else happens elsewhere, we react to that,” said the member. “But the overall way in which we can deal with these challenges requires a well-thought-out strategy. Today, there is an asymmetry between India and China, and, if that asymmetry expands, our room for manoeuvre gets limited. So, how do we get out of that?”

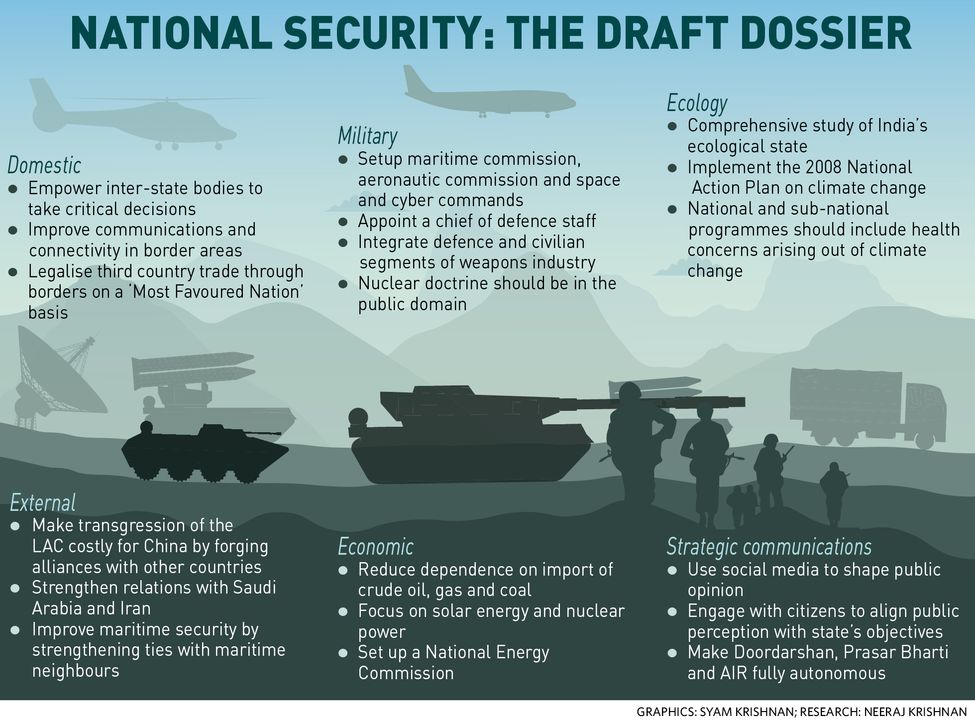

The draft doctrine covered six dimensions—domestic, external, military, economic, ecological and strategic communications. The point was that India’s options should not get limited with a growing asymmetry. “If the asymmetry becomes so large on its borders with any of its neighbours, there will be no military options left,” said the member. “The enemy does not need to fight a war then. So, how do we make certain that we have at least the minimum capabilities, so that if the adversary wants to do anything, it is clear to him that it will be a risk?”

The Saran-headed board had made specific recommendations like “the need to deploy additional air strike capabilities and attendant ground facilities to deal with the logistic and transport asymmetry on the Sino-Indian border”; the need for “power projection using naval assets” by giving priority to the Indian Navy among the three armed forces; and appointing a chief of defence staff who will be a senior authoritative interface of the armed forces within the government to promote “jointness” of military forces to meet challenges of modern warfare.

The focus on maritime assets was explained in terms of expanding footprints of both India and China in southeast Asia and east Asia. Though the Indian Ocean is low on China’s priorities at present, given its preoccupation in the Yellow Sea, Taiwan Strait and South China Sea, the presence of Chinese navy in the Indian Ocean will become more ubiquitous, Saran told Modi. India’s edge in the Indian Ocean could be eroded if it does not build up the quality and reach of its maritime assets.

Another key recommendation was on the need to develop nuclear capabilities based on the no-first-use doctrine. For a no-first-use doctrine to be credible, it should be backed with a robust retaliation capability, after suffering the first attack by the enemy. “Unless you have survivable forces, you cannot have that capability,” the board said. India needs to focus on not only having more nuclear submarines in the next few years, but also longer-range ballistic missiles that can be fired from those submarines. “India must also take into account the possibility of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons or dangerous fissile material falling into the hands of jihadi or terrorist elements who may target India,’’ the draft doctrine stated. There was also stress on strengthening a ballistic missile defence system against the possibility of a first attack by the enemy.

The draft had talked about the importance of strategic communication. It even suggested making communication a part of each cabinet note, where it would explain how the government should use the media to communicate its policy decisions to the citizens. The doctrine wanted to change the all-too-secret image of the government.

But, why do we need a doctrine? “When the business of the state has become so complex, not having that broad picture in front of you can lead to inefficient decision-making,” explained Saran. “What the national security strategy does is to give you a certain degree of coherence in dealing with the challenges you face. It comes with a clear picture of what you are trying to achieve not in the immediate term but in a five-year, ten-year or fifteen-year time frame.”

According to Narayanan, a national security strategy is a combination of “both actionable points as well as an overarching policy framework”. “Definitely, we need a national security strategy, which is why it has been in the works for the last 10-12 years,” he said.

Strategy is about making choices because you cannot do everything, summed up Saran. “Every country needs to decide what is important and what is not,” he said, “what is a greater priority and what is not, so that you direct the limited resources you have to what your priorities are.”