Twenty kilometres outside Jammu lies the Kot Bhalwal jail, one of the most notorious high-security prisons in Jammu and Kashmir—a place even hardened criminals dread. Ask former inmates about the jail, and they would tell you stories of torture and humiliation. “The jail is overcrowded, dingy and suffocating,” said a former inmate. “The food is substandard and unhygienic.”

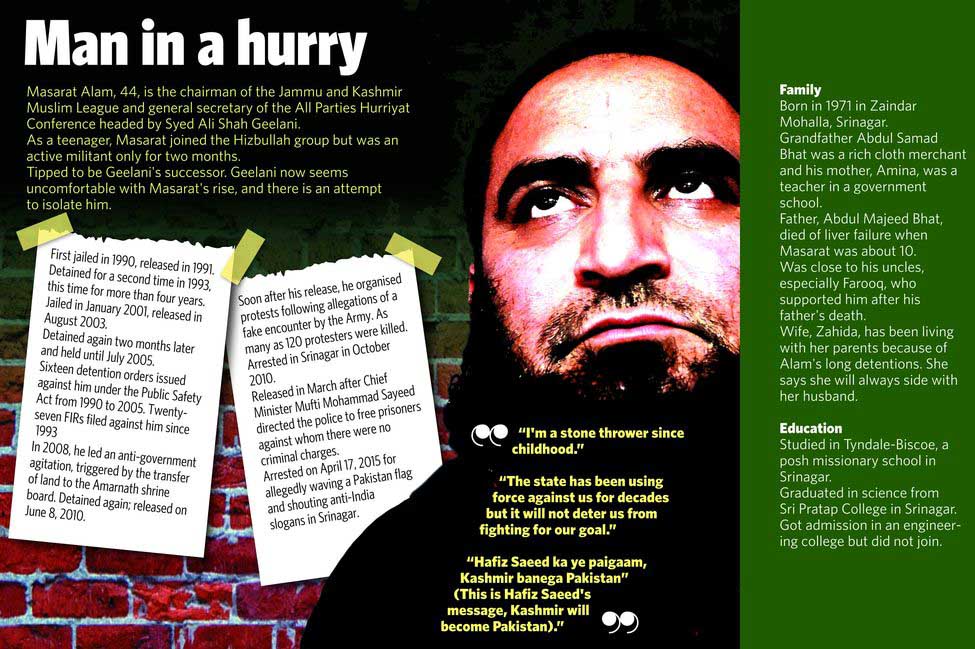

But, for security agencies, Kot Bhalwal is the perfect place for the person they call “Kashmir’s most dangerous man”—Masarat Alam Bhat, founder of the separatist Jammu and Kashmir Muslim League. Over the past five years, Masarat has instigated hundreds of young Kashmiris to revolt against the government. In fact, his reputation has made him the predominant separatist leader in Kashmir.

At Kot Bhalwal, Masarat shares his cell with a group of political prisoners—Kashmiri separatists detained for various reasons. It is a dingy room, whose only luxury is a fan. But that hardly helps during summer (March to October), when the jail is teeming with insects, and even snakes.

Masarat's days begin with fajr namaz at dawn. He and two other Kashmiri prisoners used to cook their own food during Ramadan, as there was no provision in the jail to serve food at night. Now they eat at the jail mess. Most of Masarat’s time is spent reciting the Quran and Islamic texts. He also reads newspapers and borrows books from the jail library.

“We are for a peaceful political struggle. Martyrdom and jail are part of the freedom struggle,” Masarat conveyed to THE WEEK through Muslim League leader Abdul Ahad Parra, who met him at a high-security cell at Kot Bhalwal. “This [imprisonment] will not dampen our spirits. The Kashmiri nation needs to unite. Inshallah, the dawn of freedom is not far.”

It was his first statement after he was arrested in April. Masarat, 44, has spent 17 of his past 25 years in jail. “His health is not good, but he is steadfast,” Parra told THE WEEK. “He is determined and focused on his goal.”

At Kot Bhalwal, there is no difference between a criminal and a political prisoner. That is why Masarat’s uncle Farooq Ahmed Bhat recently filed a petition in the High Court requesting that he be shifted to a jail in Srinagar as his life was in danger. The state government argued that shifting Masarat to Kashmir would affect law and order in the state, and that there was no threat to his life, as he was kept under tight security.

But, on June 2, the High Court directed the government to consider shifting Masarat to the Central Jail in Srinagar, or any district jail in Kashmir, by June 11, citing a rule that a detainee be lodged in a jail close to his place of residence. Wary, the government is yet to transfer him.

Security officials say Masarat is now the only crowd-puller among separatists in the valley. In the past five years, he has built up a reputation as a new-age radical, one who can mobilise Kashmiri youth by appealing to their romantic notions of azadi, or freedom.

In the summer of 2010, what started as small protests over the killing of three civilians by the Army in a fake encounter at Machil in Kupwara district soon morphed into the most virulent uprising ever in Kashmir. The catalyst of that change was Masarat, who had been released from detention just days before a tear gas shell fired by security forces killed Tufail Mattoo, a 17-year-old boy, in Srinagar.

Graphics: N.V. Jose

Graphics: N.V. Jose

The uprising quickly reached a stage where the authorities realised that they needed to arrest Masarat to douse the protests. But it took them five months to nab him. By the time Masarat was back in jail, the relations between Kashmir and New Delhi had reached breaking point.

Masarat was released again in March this year. Barely a month later, security analysts, who had warned that he was a far bigger threat than hardline separatist Syed Ali Shah Geelani, were vindicated. On April 16, at a rally organised to welcome Geelani back to Srinagar after his sojourn in Delhi, Masarat raised slogans supporting Pakistan and Hafiz Saeed, chief of the Pakistan-based Jamaat-ud-Dawa and its militant wing, Lashkar-e-Taiba. As the crowd waved Pakistani flags and cheered him on, Masarat turned the show into a pro-Pakistan rally.

The incident left the PDP-BJP government, barely two months old then, red-faced. The following morning, Masarat was back in jail. He had tasted a mere 40 days of freedom after four years of incarceration.

He had done the damage, though. Every separatist rally in Kashmir now features a good number of youngsters, inspired by Masarat, waving Pakistani flags. This has happened at a time when most separatists in the state have resigned to failure and compromise.

With his subversive zeal and hard-hitting rhetoric, Masarat has become the dominant separatist leader of his generation. His has been unlikely journey. As a boy, he was raised in riches, went to the elite Tyndale-Biscoe School in Srinagar—former chief minister Farooq Abdullah is an alumnus—and was selected to an engineering college. But he ended up an Islamist, a staunch Pakistan supporter and, now, a darling of Kashmir's restive youth.

Masarat was born in 1971 at Zaindar Mohalla, a neighbourhood of Muslims and Pandits in Srinagar. His grandfather Abdul Samad Bhat was a wealthy cloth merchant who owned a chain of shops at the nearby Chinkral Mohalla. Abdul had four sons—Assadullah, Abdul Majeed, Farooq Ahmed, Parvez Ahmed—and a daughter. Majeed, Masarat's father, and Farooq entered the family business, while Assadullah and Parvez became government employees. Assadullah retired as an engineer and Parvez, as a senior officer of the Food Corporation of India.

Amina, Masarat's mother, is a former government teacher. Masarat was in class three when Majeed died of liver failure. His mentally challenged sister did not attend school. Amina was forced to return to her parents’ house after her father argued that sharia prohibited her from continuing to live with her in-laws. But Masarat's uncles, especially Farooq, refused to let go of the children. So Amina had to leave them behind.

“In Farooq, Masarat and his sister found a loving father, guardian and friend,” said an old neighbour. “Even Masarat’s father would not have made the sacrifices that Farooq made for him.”

Farooq's devotion to Masarat has been unwavering, say neighbours. Masarat's decision to become a militant, and then a separatist, has taken a toll on Farooq. Thanks to the slew of cases against Masarat, he spends most of his time visiting police stations and courts. The riches the family had once enjoyed are long gone. Farooq now runs a small shop selling sanitaryware. “His sister [Farooq’s daughter] is getting married, and we were jubilant that he [Masarat] was home,” said Farooq, tears falling on his flowing grey beard.

Zahida, Masarat's wife, is still supportive of her husband. “When we got married in 2005, I knew what I was getting into,” she said. “There are scores of women like me in Kashmir.” Thanks to Masarat's long detentions, Zahida has lived at her father's house for most of her married life.

Masarat has won praise from many Kashmiris for marrying a woman from a modest family, and whose brother was killed by security forces. Unlike him, many separatists leaders married upper-class women, some of them foreigners.

Amina said her son was a sincere man. “He was selected by an engineering college, but refused to join it,” she said. “But he completed graduation in jail.”

Amina said J.N. Saxena, former director-general of police, “was ready to release Masarat after he was selected to the engineering college at Hazratbal [National Institute of Technology]”. But one of Masarat's longtime friends said the separatist leader had secured admission at an engineering college in Bengaluru. “I remember seeing his interview card,” he said. “But he didn't join.” Another friend described Masarat as generous and politically aware. “He admired Muhammad Ali Jinnah from an early age,” he said. “Once, he sold his shoes to purchase cloth to make a Pakistani flag.”

A neighbour said Masarat used to “organise Quran recitations and naat (poems in praise of the Prophet Muhammad) competitions on Pakistan day”. It was Geelani who solemnised Masarat’s nikkah on August 14.

Masarat’s former classmates say he was an early rebel. “In his first successful agitation, he led a group of boys who demanded permission for Friday prayers,” said one of his classmates. “The school authorities had to budge.”

In the late 1980s, Masarat joined Hizbullah, founded by veteran separatist Mushtaq-ul-Islam, and became an active militant. But he quit two months later and was first arrested in 1990. Three years later, after he was released, he co-founded the Muslim League with Mushtaq.

The same year, the Hurriyat Conference was formed, with Mirwaiz Umar Farooq as its chairman. During the 2002 assembly polls, which saw the defeat of the ruling National Conference and the emergence of the Peoples’ Democratic Party, Geelani took umbrage at the decision of Sajjad Gani Lone of the Peoples’ Conference, a constituent of the Hurriyat, to field proxy candidates.

Masarat backed Geelani. He demanded that they either change the “driver of the bus” (the chairman of the Hurriyat) or get off the bus. The Hurriyat split on expected lines—moderates and hardliners—in 2003. Geelani floated his own Hurriyat faction and Masarat became its first convener.

He cemented his position as a possible successor to Geelani in 2007, when he organised a shutdown in the Mirwaiz's stronghold of downtown Srinagar to protest the Mirwaiz's talks with New Delhi. He followed it up with a big rally for Geelani at Eidgah in Srinagar, another Mirwaiz territory. “That is when we realised that he was a threat,” said a police officer.

Masarat was soon arrested and was charged under of the Public Safety Act. When he was released in 2008, the Amarnath temple land row was on the boil. Masarat proposed a coordination committee to protest the state government's decision to transfer land to Shri Amarnath Shrine Board at Batlal in Sonamarg. Sixty people died in the agitation that followed. The government was forced to cancel its decision, and Masarat was jailed for two years.

He was released in 2010, and became the driving force behind the uprising of that year. For security agencies, tracking Masarat down proved to be one of the most toughest operations ever. After S.M. Sahai took over as the inspector-general of police, a special team was put in charge of tracing Masarat. The team rounded up Geelani and many of Masarat's friends, neighbours and aides. But, much to the police’s dismay, Masarat continued to appear before crowds in several parts of Srinagar and then vanish without a trace.

A brief respite: Masarat and his niece at his home in Srinagar, after he was released in March | Getty Images

A brief respite: Masarat and his niece at his home in Srinagar, after he was released in March | Getty Images

Masarat's show of defiance and the mounting civilian casualties prompted calls for the resignation of chief minister Omar Abdullah. The uprising peaked on June 24, when the coordination committee headed by Masarat launched the ‘quit Kashmir’ movement.

Reflecting on the mayhem that Masarat had orchestrated in 2010, a senior police officer said they got it wrong by assuming that detaining Geelani would defuse the crisis. “We should have got Masarat instead,” he said. “Unlike Geelani, he could move around, mix with the mob, change locations, ride a bike and melt away.”

Every day, young boys, responding to Masarat’s calls for protest, would emerge from the narrow lanes of Srinagar, Sopore, Pattan, Budgam, Tral, Shopian, Pulwama and Anantnag, and clash with security forces. Security analysts began referring to the violence as “India's intifada [‘uprising’, in Arabic]”, drawing comparisons between it and the Palestinian stone-throwing and mass demonstrations against Israeli forces that started in the late 1980s. B. Raman, former head of the counterterrorism unit of the Research and Analysis Wing, was quoted saying, “What we are witnessing in certain areas of Jammu and Kashmir is the beginning of an intifada. The root cause is the growing perception among sections of the youth that the security forces have been insensitive in performing their counter-insurgency duties and have been adopting objectionable methods… and using disproportionate force against the people.”

When the forces ultimately put a lid on the situation, as many as 120 civilians, mostly young boys and women, had died. More than 500 people were injured, some of them handicapped for life.

The role Masarat played in the unrest catapulted him to the top rung of the separatist hierarchy. He had planted the idea of secession in the mind of a generation born and raised during the tumultuous years of militancy. Security experts have since categorised him as “dangerous” and as “the next big threat”.

Ashiq Bukhari, the senior superintendent of police who led the operation that resulted in Masarat’s arrest, said it took the police months of hard work to track him down. Now retired, he said his team got Rs10 lakh the police had put on Masarat's head. “Omar gave us an extra Rs15 lakh from his own pocket,” he said.

According to him, Masarat’s release in March this year in no way contributed to peace in Kashmir. The reference, obviously, was to PDP president Mehbooba Mufti's statement, made after Masarat was released, that her father, Chief Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, was a man of peace.

Omar justified the long detentions of Masarat, saying it saved lives and allowed smooth elections. “The summer of 2010 was never repeated again, not even after Afzal Guru’s execution,” he said. “A reason for that was the absence of Masarat.”

Observers say Masarat has emerged as a major political force as he does not shy away from taking risks. “He is free of family and business compulsions,” said a senior journalist. “Such compulsions have forced many separatists to moderate their stance.”

Masarat has occupied the space that has been lying vacant in Kashmir after militancy was crushed. Even moderates now consider him favourably, as is evident from his growing support in Srinagar, Pattan, Sopore, Baramulla and Shopian.

Many educated youth now look up to him. In fact, many of them helped Masarat evade the police in 2010. THE WEEK traced some of those supporters. “He travelled at night and changed location every ten hours,” said one supporter. But one day, he was nearly trapped. Masarat, said the supporter, was hiding in a house in downtown Srinagar when the police arrived in the neighbourhood. The owner of the house hid Masarat in the attic. When the police began searching the houses, Masarat climbed on the roof, tiptoed over the roofs of adjacent houses, got down into a narrow lane and fled.

The supporter said Masarat could flee because the owner diverted the police’s attention by fleeing in a similar fashion in a different direction. “Before the police could fathom what was happening, both of them had escaped,” said the supporter.

Another time, Masarat ran out of safe houses. “He told us, ‘You have done your bit, now I am on my own’,” recalled another supporter. “That day he wore a T-shirt, shorts and slippers, hid his flowing beard by wearing a black helmet and rode a bike. He drove around the streets and nobody had any clue it was him.”

Sources told THE WEEK that after Masarat was released in March this year, he visited families of the men who were killed in the 2010 uprising. An intelligence officer said Masarat met families in Srinagar, Baramulla, Pattan and Sopore. “Had the Mufti not wilted under pressure from the BJP and ordered his arrest, he would have embarked on mass contact,” said the officer.

Another security officer told THE WEEK that Masarat gave the families money collected from his relatives and well-wishers. “[It was] a very small amount,” he said. “But such gestures win you a lot of admirers.”

Masarat’s biggest enemy could well be his popularity. A leader of a pro-independence group in Kashmir said Geelani was feeling insecure at Masarat’s rise. Geelani’s supporters began a whisper campaign against Masarat after he was released in March. One of them compared Masarat's release to Sheikh Abdullah's release in 1975, alluding to allegations that Sheikh had reached a compromise with prime minister Indira Gandhi.

A senior journalist, however, said Masarat's record as a separatist was unblemished, unlike in the case of Geelani. “How did Nayeem Geelani, Geelani's son, land at Delhi airport from Pakistan, when Kashmiris who went to Pakistan during militancy had to return via Nepal, surrender and then be questioned by the police? They were allowed to unite with families only after they got clearance from CIK [counterintelligence of Kashmir],” he said. “Did Nayeem go through all this?”

Former R&AW chief A.S. Dulat's book Kashmir: The Vajpayee Years has dented the credibility of separatists like Geelani, Mirwaiz, Yasin Malik and the late Abdul Gani Lone. Security analysts believe that Dulat's damaging inside account of murky dealings between New Delhi and separatists is the reason for the newfound bonhomie among separatists. For the first time in eight years, separatists of various political hues gathered at an iftar party hosted by Geelani in Srinagar on July 11, and broke the fast together. Their decision to organise a rally to observe martyr’s day on July 13, to commemorate the killing of 22 Kashmiris by the forces of the erstwhile maharaja in 1931, however, was foiled by the government.

Two senior police officers told THE WEEK that they preferred Geelani to Masarat at the helm of the separatist hierarchy. “Masarat does not have any weak links that the state can exploit,” said one officer. The other reasoned that Geelani’s interests are intertwined with that of his children.

Sources said efforts were being made by a section of separatists to isolate Masarat. Many believe that the rally on April 16 was actually a trap to send him back to jail. But, it seems, Masarat knowingly walked into that trap to maintain his credibility.

Soaring stock

EVER SINCE he led the 2010 uprising, Masarat Alam Bhat's support base has widened across Kashmir. Separatists in Baramulla, Pattan, Sopore and Kupwara consider him the true successor to hardline separatist Syed Ali Shah Geelani.

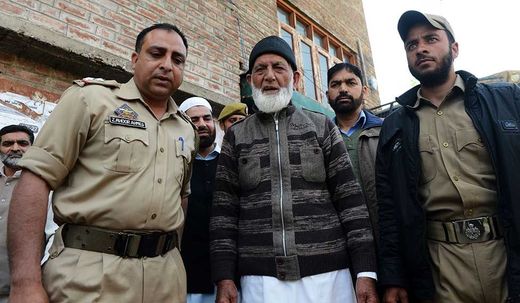

On his way out? With Masarat's rise, hardline separatist Syed Ali Shah Geelani (centre) has lost his grip on the radical discourse in Kashmir | AFP

On his way out? With Masarat's rise, hardline separatist Syed Ali Shah Geelani (centre) has lost his grip on the radical discourse in Kashmir | AFP

In the 1990s, pro-Pakistan supporters rallied behind Geelani and his Jamaat-e-Islami. Most of them now support Masarat for his hardline stand and the role he played in the 2010 uprising.

Masarat fits in their scheme of things. He is an uncompromising Islamist and commands influence among militant outfits—factors that made Geelani popular at the expense of moderates.

The rally in April this year showed that Masarat had raised the bar for separatists. Geelani's grip on the radical discourse has loosened, as evident from the fact that two former members of the Jamaat-e-Islami, who were considered Geelani supporters, were killed in June, allegedly by a rebel group of the Hizbul Mujhahideen.

Some analysts believe that the group, which calls itself Lashkar-e-Islami, targeted the Geelani sympathisers to send a message against abandoning the “cause”. For his part, Geelani has blamed security agencies for using Lashkar-e-Islami against separatists and their supporters. He cited the statement of Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar that the government “will use militants to target militants”.

Masarat has consolidated his influence at Tral, Shopian and Anantnag in south Kashmir, which were once militant strongholds. Tral and Shopian, in particular, have emerged as his new support centres. His radical approach has caught the fancy of the restive youth in these areas.

Masarat, however, is most influential in Srinagar, especially the volatile downtown area, where hundreds of young men responded to his calls for protests in 2010. Most of them openly celebrated his release in March this year.

The truth is that whoever commands influence in downtown Srinagar calls the shots in the separatist discourse. The youth, mostly college students, are enamoured by Masarat's hard-hitting rhetoric. Their support served him well in 2010, when the police were hot on his trail.

In Kashmir, public opinion is often swayed by the rhetoric of hardliners. The so-called “islands of radicalism” force their agenda on the neutral and moderate crowd during times of crisis, as was the case in 2010. And, this is where Masarat has carved a place for himself.