On April 17, while inaugurating a private hospital in Surat, Prime Minister Narendra Modi anno-unced there would soon be a law to ensure that doctors prescribed only ‘generic’ drugs. A day later, the Union ministry of health and family welfare released a notice asking doctors to follow the Medical Council of India’s (MCI) existing guidelines on using generic names of drugs in prescriptions.

According to MCI rules, “every physician should prescribe drugs with generic names legibly and preferably in capital letters, and he/she shall ensure that there is a rational prescription and use of drugs.” The words “legibly and preferably in capital letters” were added after an amendment last year. Following the PM’s statement, the MCI, too, reiterated that doctors follow this rule “without fail”.

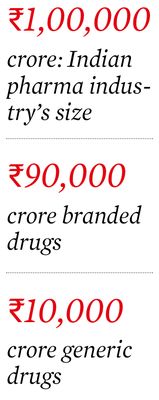

The announcement, ostensibly to disrupt the pharma-doctor nexus, has become controversial in light of several issues raised by experts, most of whom support the cause of affordable care. The drug market in India is dominated by branded generics, like the several branded versions of paracetamol such as Crocin, Calpol and Pacimol.

Within the branded versions of the same generic, at times, the price differential can be significant, say doctors. “In that context, it is unclear whether the government wants doctors to prescribe generic names of drugs or the cheapest version of the branded generic,” says Dr Ashwin Kamath, a Manipal-based pharmacologist.

In medical schools, doctors are taught to write generic names, but Kamath says that issues of quality prevent them from doing so. Owing to the variations in the market—several companies may be marketing the same drug—doctors prescribe brands based on their experience of what works and what doesn’t. And, compelling doctors to write generic names instead only shifts the responsibility to a chemist to decide the brand, says D.G. Shah, secretary general of Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance. “The costs will anyway go up because trade is demanding higher margins on generics [50 per cent] as against branded generics [30 per cent],” he says.

In principle, doctors agree that the patient should not be charged excessively for a medicine. “In practice, however, the problem is that there is no quality control when it comes to drugs. Medicines are being manufactured in small shops with suspect quality,” says Dr Ajay Swaroop, chairman, department of ENT at Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi.

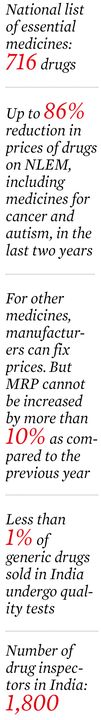

Dr K.K. Aggarwal, president of the Indian Medical Association, agrees. “The government itself admits that less than 0.01 per cent of the drugs produced in the country are tested for quality. It would be unfair to expect doctors to prescribe substandard drugs then,” he says.

It is not that there aren’t enough laws to ensure quality of drugs, say experts. But issues around proper implementation and adequate manpower remain. Aggarwal says the current count of 1,800 drug inspectors is grossly inadequate for the entire country.

When it comes to drug testing, many say that since most manufacturers eschew bioequivalence studies (mandatory only for exports though)—to test whether two medicines, such as an original patented drug and a generic, work in the same way—drug quality is affected in a big way.

On April 3, a notification by the Union health ministry made bioequivalence studies for certain classes of drugs mandatory after an amendment in the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940. “Virtually none of the existing drugs in the market have tested for bioequivalence. The government should make it compulsory for all of them [instead of only some],” says Prashant Reddy, research associate at the School of Law, Singapore Management University.

Reddy, who has worked on drug regulation, says the credibility of the organisations conducting these studies was also suspect, going by recent cases where some of these organisations were red-flagged by WHO or foreign regulators for poor clinical practices, including fudging data on bioequivalence studies.

To address the quality issue, Dinesh Thakur, public health specialist and chairman of Medassure Global Compliance Corporation, says the government would need to bring drug regulations on par with globally acceptable standards, get qualified people to enforce them and hold people who make substandard drugs accountable under existing laws.

For the doctors, Kamath says there should be adequate information available on whether the drugs have cleared bioequivalence studies, and whether quality was being maintained even after clearance.

Bhopal-based pharmacist Ram Chandra Marvya, however, disagrees. He runs a Jan Aushadhi store (fair price shop for medicines) under the Centre’s Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Jan Aushadhi Pariyojana. He insists the quality of the unbranded generics at his shop has never been an issue, and denies allegations of shortage of popular medicines. Instead, the problem is of access. “Most of my clients are educated people who are aware that they can buy cheaper medicines here. The poor, who really can’t afford costly medicines, do not know where to buy them,” he says. “Aware-ness should be created about these shops, and the government should have one such shop at every primary health care centre.”

Marvya says since the price differentials are huge—a strip of ten tablets of cetrizine (anti-allergic) costs Rs 1.84 at his store as against the Rs 16 to Rs 43 for a branded version—many pharmacists also stay away from setting up a Jan Aushadhi store. “Pharmacists need to be motivated to set up affordable medicine shops,” he says, “and customers must check drug prices to ensure that they are not being taken advantage of, by the chemist or by the doctor.”