A few days after the Pakistani Taliban gunned down 14-year-old Muhammad Shaheer Khan, along with at least 144 others, at the Army Public School in Peshawar last year, his mother received the black gloves he had worn to school that day.

“It was cold,” she told me, about the last morning she had seen him.

It was cold, too, on the night we met, earlier this week. We were sitting on the roof of the home of a couple, Mr and Mrs Aurangzeb, whose son was also massacred.

Aurangzeb has created an open-air room on his rooftop that functions as a shrine to his son and a gathering place for other mourning parents, who meet there twice a week. A poster of the photos of the murdered, mostly schoolchildren, runs the length of one wall. Green banners inscribed with Quranic verses hang on another.

It was two days before December 16, the anniversary of the massacre, and six couples—bundled in overcoats, woollen scarves covering their mouths—had assembled.

When she received the black gloves, Muhammad Shaheer’s mother said, she asked her maid to wash them. “Suddenly, the maid cried, ‘There is blood in these!’ so I rushed to see. Blood was leaking from inside the gloves. I told the maid to get aside,” she said. “I will wash the gloves myself. This is my child’s blood, my own blood.” She touched her stomach. “You see, when my child was shot, he must have put his hand on his stomach to ease the pain.”

The other mothers mechanically wiped away tears.

“So I washed them myself, and the whole tub was filled with blood,” she said. “Then I took the bloodied water and watered my plants with it. It is my blood, so it will stay in my home.”

“But my tears have dried up,” her husband said. He is short and stocky, and introduced himself as a businessman. “Will you please let me talk for five minutes?” he asked, dragging a plastic chair closer to where I was sitting. “No one should interrupt me.”

“What has the government done for us? They have only given us medals. And these medals have gone black, just like their hearts. What operation is the army doing? Which terrorists are they hanging? Why don’t they show us the photos of the dead terrorists? I would like the government to hang them in the square of this city, so I can go and spit on them. When my child and the children of these parents were killed, they took them to the hospital in Suzuki vans like cut-up pieces of meat.”

He pointed at our host. “Mr Aurangzeb, here, his son called him from his cellphone after he was shot, to say: ‘Baba, bring me water. I am feeling thirsty.’ His father rushed to the school with two guns in his hands to kill the terrorists himself but he was not allowed in. Please excuse my language—I should not be using this word in front of women—but what have these b**s done for us other than give us rusting medals?”

In the years leading up to the massacre, a debate raged in Pakistan: Are the Taliban our enemies or are they “misguided” Muslims?

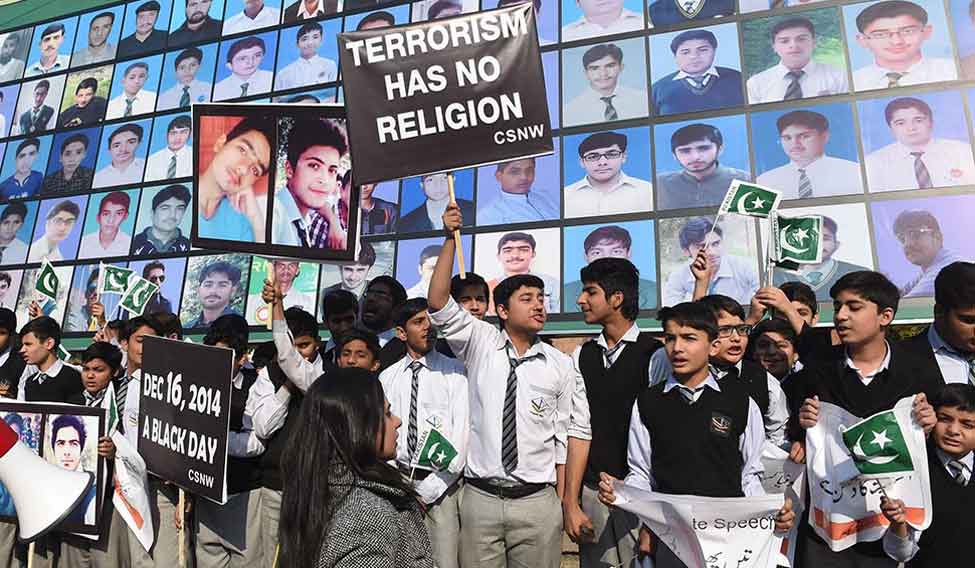

Pakistani students and civil society activists gather beside a board bearing images of victims of the Peshawar massacre, the deadliest terror attack in Pakistan's history | AFP

Pakistani students and civil society activists gather beside a board bearing images of victims of the Peshawar massacre, the deadliest terror attack in Pakistan's history | AFP

Increasingly, the latter narrative was winning out. Its greatest proponent was Imran Khan, the cricket star-turned-politician, who insisted that the government engage the Taliban in peace talks instead of hunting them down because they were “our people, Pakistanis”. The Taliban have historic grievances with the United States, the argument went, and Pakistan is caught in the middle because of its greed for American dollars. The Taliban don’t hate us—they just hate our government’s foreign policy.

The Taliban, energised by the government’s wilful impotence, began to kill with impunity. In the last 10 years, more than 50,000 Pakistani civilians—innocent men, women and children—perished in the war on terror.

Then the Taliban attacked the Army Public School on December 16, 2014. For years, Pakistan’s security establishment had resisted decisively moving against the Taliban; it had, in fact, nurtured some of these terrorists as assets in Afghanistan. But now the army was humiliated—an army school had been attacked, army children killed. Suddenly, the Taliban were not misguided Muslims. They were murderers. Politicians, who had previously described the terrorists in painstakingly diplomatic terms, began to curse them. The Pakistani mindset, which had veered from lamentation (when the Taliban attacks began) to fear (when high-profile politicians began to be assassinated) to denial (when “talks” gained traction) had changed: The people were now angry.

Significantly, the establishment delicately altered the notion of martyrdom. The word for martyr in Urdu is “shaheed”. To achieve martyrdom—or "shahaadat"—is to be elevated to the highest ranks in heaven for a patriotic sacrifice made on earth. The word had been reserved for Pakistani soldiers killed in war. Now schoolchildren and teachers who had been killed as they sat peacefully in an auditorium were all shaheed, because the Army said so. The message was this: Our children did not die in vain; they are the reason we have gone after the people’s enemy.

Today, a year has passed. The Army Public School has undergone intensive renovation. Brass plaques inscribed with buoyant religious verses adorn the grounds. New vigour has been applied to the operation against the Pakistani Taliban in the mountains of Waziristan. The names of dead terrorists routinely appear as front-page news.

But on the Aurangzeb’s rooftop, the posters of dead children flutter in the wind. The parents, who still feel that far too little has been done, cling to their memories. "My son used to bathe so well, so well,” says Muhammad Shaheer’s mother, “that when he would come out of the shower, shining white, we would say, ‘Look, it’s Katrina Kaif!'”

Another mother looks me in the eye. “There is one thing—one word—that has given me support in this difficult time. That word is ‘shaheed'. I don’t know how I would have survived if this word did not exist.”