Are there civilians trapped in the ruins?”

I asked a soldier belonging to a Shiite militia group, which was part of the offensive to liberate Mosul. The battle for Mosul, which started last October, is drawing to a close, with Iraqi Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi declaring victory on July 9. Sporadic clashes, however, still continue, especially in the old city. The regular Iraqi army, the Golden Division special forces and the federal police have been leading the campaign against Islamic State.

The soldier laughed, and pointed to the battle tanks in the street, which were decorated with flags to mark Iraqi victory. “They are all under the rubble,” he replied, reminding me of the dirty part of the war. By the end, the war was about prisoners tied to the ground waiting to be questioned, and dead bodies lined up in rows inside buildings, as after a mass execution.

Another face of the war: soldiers carrying on their backs women and children, who came like ghosts from the ruins of the old city. They were wounded, hungry, barefoot and in tears. In a word, desperate.

Two days before the end of the war, General Fadhil Barwari, the commanding officer of the special forces, was looking at an old city map at his base in west Mosul. He was barely 200 metres from victory.

“What about civilians?” I asked him.

Winning moment: Iraqi Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi at an event in Mosul to declare victory over IS | Reuters

Winning moment: Iraqi Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi at an event in Mosul to declare victory over IS | Reuters

“We are waiting only to rescue the kids,” he said. “All others will die. We have pictures of women fighting. Those who stayed back till now, have done so to fight. We will save the children because they are our children, too. They are the children of Iraq. We will not have pity for anyone else.”

The advance of the special forces in the last hours of the war was quite dangerous. The IS terrorists had turned houses into booby traps. There were electric cables everywhere, set up to blow up everything.

“Many civilians died like this,” said a major from the special forces. “We have evidence that IS locked up dozens of civilians in the basements of the houses. We fear they were blown up trying to get out.”

In the last hours of the war, IS terrorists even sent their women to die. The wives came out of the narrow, destroyed alleyways of the old city, holding their children in their arms, asking to be saved—and they blew themselves up, killing civilians, soldiers and their own children.

“We can ask men to undress in front of us to check for explosives or weapons, but we cannot do that with women. Our religion does not allow that,” said Usama, a young soldier from the special forces. “It was dramatic. All of them seemed to be our enemies. We could no longer make out whom to save and whom to suspect.”

Walking in the old city today means walking along a stretch of ruins and corpses. The smell of putrefied bodies is sickening. And, like in the case of many other wars, it is difficult to accurately estimate the losses, both civilian and military.

Bombs have destroyed 80 per cent of the buildings in the old city. There are entire neighbourhoods, some stretching up to a kilometre, where there is not a single building that has not been hit. From the rubble, remnants of homes and cars emerge. Then suddenly, there are legs, arms and heads. It is hard to say whether they belonged to terrorists or civilians.

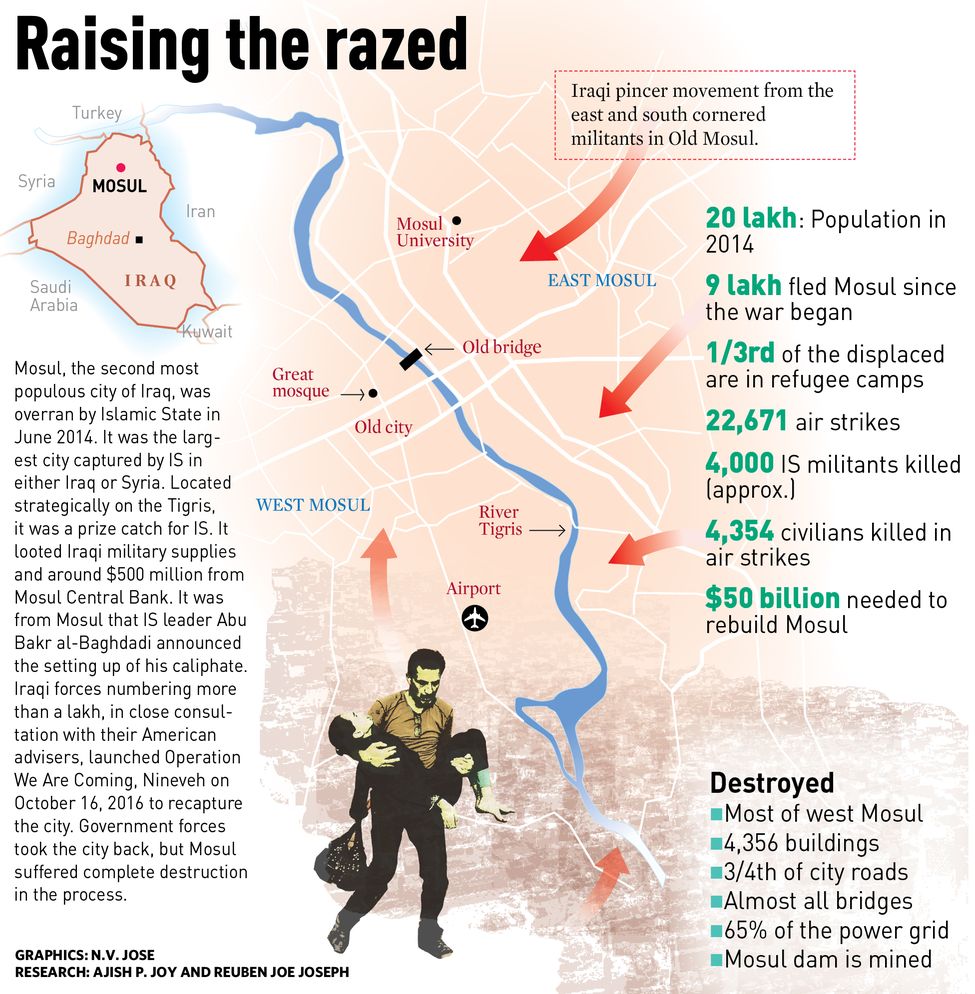

The humanitarian situation is really difficult. According to Iraqi government data, about nine lakh people fled Mosul after the war began. Nearly one-third of them are in refugee camps in Iraqi Kurdistan. Many have decided to return despite the lack of water and electricity. Damage to infrastructure is estimated to be worth a billion dollars.

At Jadida in west Mosul, I met 11-year-old Mohammed, whose family chose to return to their home. There is no water, electricity or food. Still, they would rather stay here in the rubble than in a faraway refugee camp. On the walls of their home are holes made by IS terrorists. “They forced men to make these holes, and then forced our families to follow them, to use them as human shields,” said Ibrahim, Mohammed’s brother.

Those who returned to Mosul have started slowly rebuilding their lives, closing the holes in the walls, waiting on endless queues for water, and praying for their loved ones.

Mohammed’s elder brother was killed by terrorists because he worked for the government forces as a barber. His mother can’t stop crying looking at his photograph.

Mohammed attends a school in the afternoon, which has been set up to help children who missed their classes for years.

“Will you forgive the IS terrorists? And, their children who were forced to join them?” I asked him.

“No,” he said. “I will not forgive anyone. They have ruined souls and lives. There is no forgiveness.”

These are the words of a child who has seen brutality. Recovering the future of Iraq involves recovering the lives of children like him.

On July 10, Prime Minister Al-Abadi was at the base of the Golden Division to congratulate the troops. There were Iraqi flags on the tanks. The soldiers shouted.

“From here, from the heart of the free and liberated Mosul, by the sacrifices of the Iraqis from all the provinces, we announce the awaited victory,” said Al-Abadi, surrounded by Iraqi and Kurdish commanders. “I declare the end, the collapse, and the failure of the false terrorist state of IS. This great feast day crowned the victories of the fighters and the Iraqis of the past three years,” he said. Meanwhile, reports appeared on July 11 that IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was killed.

I met a soldier who was still not convinced. “No,” he said. “The roots of IS are still here.”