Breaking the silence: A woman at a protest in Mumbai against Kalburgi's murder | AP

Breaking the silence: A woman at a protest in Mumbai against Kalburgi's murder | AP

On the quiet morning of August 30, a masked man walked up to Professor M.M. Kalburgi's home. He knocked on the door and called for “sir”. When Kalburgi, 77, came out, he was shot in the forehead and chest. The former vice chancellor of Kannada University collapsed in a pool of blood. The culprit fled with an accomplice who was waiting on a bike. Kalburgi's family rushed him to hospital but it was too late. Another voice of dissent had been silenced.

The peaceful residential colony of Kalyan Nagar in Dharwad, home to many academicians, lost its calm. Gun-toting men, investigators, politicians, angry students and religious heads now roamed the streets.

Kalburgi's wife, son and two daughters struggled to comprehend the loss, but said the sole reason for the killing was his ideological differences with hardliners. Malleshappa Madivalappa Kalburgi was a progressive voice from the Lingayat community, which has enormous political clout in the state, and he had had several face-offs with the conservative elements of his community. His last rites were performed in the Basava tradition of the Lingayats, with state honours.

The murder has shocked the nation, and has raised several questions about the growing intolerance towards dissenting intellectual voices. The state government held a cabinet meeting on August 31 and decided to hand over the case to the CBI. It also ordered a CID investigation till the CBI took over and extended security to prominent writers.

While the motive of the murder remains a mystery, Kalburgi's “anti-Hindu” comments, an alleged property dispute and his sour relations with a few of his own students have been listed as angles to be investigated.

One and a half years ago, Kalburgi was given police protection (later withdrawn on his request) when he started receiving threats after he, in a public speech, quoted an essay written by U.R. Ananthamurthy on “why nude worship is not acceptable” (published in 1996). Kalburgi had said that Ananthamurthy had once urinated on idols as a child. Enraged by the speech, Hindu outfits staged violent protests and threw stones at his house. There was public outcry on social media, too. A case was filed against Kalburgi for “hurting religious sentiments”.

The outspoken scholar, however, was no stranger to controversy. In 1984, his article on the birth of Channabasavanna, the nephew of saint-philosopher Basava, had ruffled many feathers. And, after massive protests at his house and many death threats, he had apologised, fearing for his family’s safety.

Kalburgi was an authority on Vachana sahitya, the founding literature of a social movement that gave birth to Lingayat community. He has written 103 books (including the popular Marga series) and more than 400 articles, and won the state and central Sahitya Akademi awards, Pampa award, Janapada Award, Nrupatunga Award and Basava Puraskara, among others. However, he had frequent altercations with religious mutts, claimed that Lingayats were not Veerashaivas (and not even Hindus), and suggested a rota system for Panchapeethadipathis (the heads of five major Lingayat mutts) to prevent them from becoming power centres. All this riled the community no end.

During a protest in Bengaluru, Professor K.M. Marulasiddappa said Kalburgi’s murder would have implications on the financial and political stakes of the dominant Lingayat community. Kalburgi had, on several occasions, received threats from the orthodox Lingayat community for his ridicule of idol worship and superstition.

The Lingayats, divided into many sub-castes and sub-sects, came together to form the single largest community (about 18 per cent of Karnataka's population) and emerged as a political force in Karnataka in 2004 after the BJP came to power under the leadership of B.S. Yeddyurappa. The community has been asking the government to classify it as a religious minority and Kalburgi had supported the demand. “Lingayatism is a non-Vedic religion and independent status would bring in social benefits, not just political or economical,” he had said. His death, however, will impact the changing cultural politics of the community.

His wife, Umadevi, who is still in shock, dismisses the property dispute theory and says she believes he was attacked by fundamentalist forces for his rationalist beliefs. The protest rallies held across the state echoed a similar sentiment.

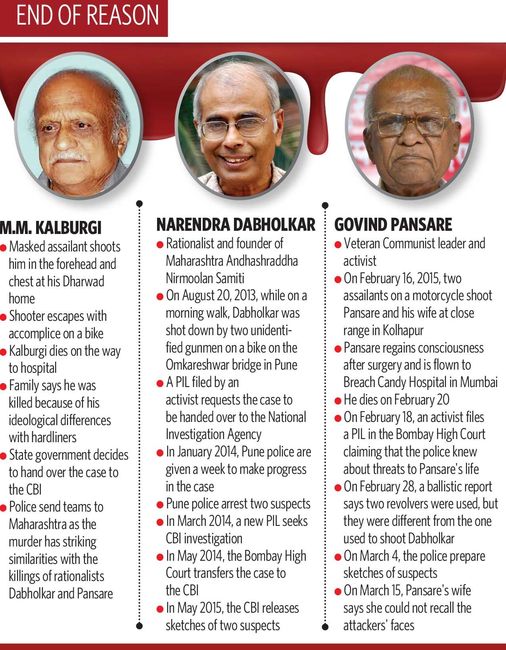

The police, meanwhile, have rushed teams to Maharashtra as, prima facie, the pattern of Kalburgi’s murder has striking similarities with the killings of two other rationalists, Narendra Dabholkar (67) and Govind Pansare (84). In August 2013, Dabholkar, an anti-superstition activist and founder of the Maharashtra Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti (responsible for the anti-superstition bill in Maharashtra), was shot dead by unidentified assailants in Pune. Last February, social activist Govind Pansare was shot dead in Kolhapur. In both cases, the assailants are yet to be caught.

The intellectual community has dubbed the murder as “an act of cowardice” and as an effort to muzzle the voices of dissent. Said noted writer Baraguru Ramachandrappa: “Fundamental forces are growing stronger and attempting to establish religious authority in the garb of democracy. The weakening of the progressive voices after the 1980s is responsible for this.”