Nepal's Deputy Prime Minister Kamal Thapa had three things to tell Prime Minister Narendra Modi when he came calling on October 17: Nepal's new constitution was not as bad as it was made out to be, the border blockade was hurting Nepal too badly and there was still goodwill for India in Nepal.

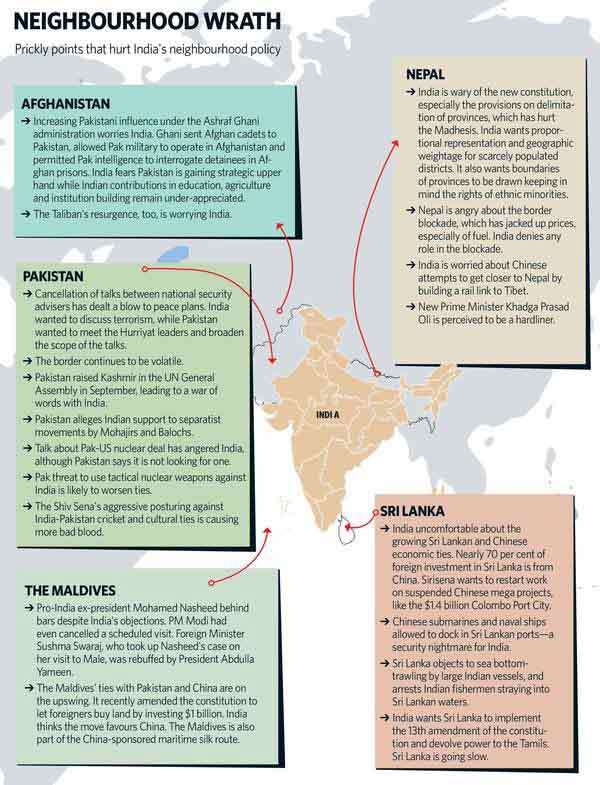

Thapa's mission was a bid to darn the relations that had frayed badly over the past few weeks. After years of civil war and social strife, Nepal had just drafted a constitution, over which India expressed misgivings. But what hurt Nepal most was that India made its displeasure known and even sent its foreign secretary on a well-publicised mission asking it to amend certain provisions.

Officials in Nepal's mission in Delhi point out, and officials in the Indian foreign office concur, that Nepal had been keeping India in the loop over the developments in the constituent assembly. But "they went back on three promises," said a foreign ministry official. "They had said there would be provisions for proportional representation, that geographic weightage would be given to scarcely populated districts while delimiting seats and that the boundaries of districts would be drawn in such a way that ethnic minorities would have enough autonomy. They went back on these."

The Madhesis and other minorities fear that they would not get adequate representation. "It is a majoritarian order," said the official. "The kind of majoritarian constitution that Sri Lanka adopted, which led to the Sinhala-Tamil strife and a civil war." The Nepalis, too, admit that their constitution is not perfect. "This is the beginning," said Nepal's ambassador Deep Upadhyay. "Yes, the boundaries are an issue. Nothing is perfect. We can discuss these issues, still."

But India would not wait. On the eve of Nepal adopting its constitution, foreign secretary S. Jaishankar landed in Kathmandu asking the Nepali leadership to hold. Nepal took it as an affront and went ahead. "Did we have to rush off the foreign secretary in full view of the world to read out India's threat?'' asked Major-General (retd) Ashok Mehta, a veteran Nepal watcher.

Meanwhile, the protesting Madhesis blocked the movement of fuel and other goods from the Indian border to the Kathmandu valley. The blockade, coming as it did on the eve of two of Nepal's biggest festivals—Dasai (Dusshera) and Bhai Tika (Bhaiyya Dooj)—hurt Nepal badly, and riots broke out. While India cried off any responsibility calling it a domestic issue, many in Nepal likened it to Rajiv Gandhi's 'vindictive blockade' of 1989 after Nepal refused to sign the transit treaty on India's terms. Said Mehta, "It is a scar that is going to show up for a long time, whenever there is an Indo-Nepalese interaction."

Indian officials say there was no attempt at arm-twisting or intrusion. On the contrary, they say the foreign secretary's visit led to positive results. "The big parties in Kathmandu were not even willing to discuss the issues earlier," said a foreign ministry official. "Now they have agreed to have a relook at the issue of delimitation. Even Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Oli, perceived to be a hardliner, has accepted that there are grievances and that he is committed to address them."

India views Thapa's mission as a climbdown by Nepal. Thapa is learnt to have pointed out to Modi and Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj a geographical reality: "We can't be anti-India; we are surrounded by India on three sides."

Indeed, Himalayan geography is not changing, but Himalayan geopolitics is. As Mehta pointed out, "Every toehold that India loses benefits China." China, which is blocked by the high Himalayas on Nepal's north, is building a rail line that would link Kathmandu to Shigatse in Tibet. Many in Nepal, and even in India's strategic circles, believe that this will end Nepal's land-locked dependence on India.

THERE ARE many who believe that Modi's 'neighbourhood first' policy is being conducted without much of a roadmap. "There doesn't seem to be a strategy in the way we handle Pakistan," said Rakesh Sood, former ambassador to Afghanistan. "Vajpayee had a roadmap without which he wouldn't have reached out to Musharraf after Kargil. There was both an element of coercion and engagement, which he tried to balance. Manmohan Singh benefited from the ceasefire and took that process forward through back channels. There was a marked continuity. But the strategy in the present case seems to be lacking."

The Modi-Nawaz Sharif meeting in Ufa had kindled hopes of renewed engagement, but following the cancellation of talks between national security advisers talks after India objected to Pakistan's reach-out to Kashmir's Hurriyat leaders, the two sides have reached a stalemate. "We are reaching out to Pakistan, but we have been insisting that you cannot take away the centrality of terrorism as an issue," said a foreign ministry official. "They are trying to put up the Hurriyat as a third party. We can't accept that."

The stalemate is leading to India missing several strategic opportunities. The US is moving to engage Pakistan in a nuclear deal and India is clueless. When asked about it, foreign office spokesman Vikas Swarup shot back, "India got a particular deal based on our impeccable track record in the area of nonproliferation. The Pakistani track record speaks for itself."

With the US struggling to find its way out of Afghanistan, Pakistan has become a factor that many countries, particularly the US, Russia and China, want to count on. India had nothing to offer when Afghan President Ashraf Ghani came calling in April, after a tour of China, Pakistan and the US. "India will have to wait," said Sood. "When Ashraf Ghani came to power last year, he decided a course of action which left us with very little room for manoeuvre."

The Maldives, once beholden to India, too, is proving to be slippery. India has not been happy with the Abdulla Yameen regime which put the former pro-India president Mohamed Nasheed in jail. "Luckily, the situation is improving, but it's always a touch and go,'' said Alok Bansal of the think tank India Foundation.

The new Maithripala Sirisena-Ranil Wickremesinghe government in Sri Lanka is perceived to be India-friendly unlike the Mahinda Rajapaksa regime. But "we will require continuous engagement with Sri Lanka," said Mehta. "Any wrong move, and China will get an edge.''

Modi's high-voltage visits and promise of credit have indeed generated goodwill in the neighbourhood, but as Bansal said, that goodwill "has to be built on through a continuous dialogue at various levels. We can never for a moment assume any nation is in our pocket.''