The crowd is restive at Numaish Ground in Muzaffarnagar, with some people making full-throated war cries in favour of Mayawati. But they are immediately warned that no slogans would be allowed once the Bahujan Samaj Party chief arrives at the venue. Before her arrival, nine party candidates are allotted only two minutes each to make an appeal. Most of them take less than a minute to finish.

At the appointed hour, Mayawati’s blue Bell 429 helicopter lands to wild applause. Alighting from the six-seater, she boards an Ambassador car, surrounded by a posse of commandos, to cover the few metres to the stage. She quickly makes it to the dais, where a sofa is kept for her in the middle. Her trademark handbag rests on the table in front of her.

After briefly acknowledging the crowd, Mayawati reads out her speech, blaming the Samajwadi Party for poor law and order, and the BJP for the riots. Then come her election promises—doling out money instead of laptops and mobiles; releasing those arrested during riots; replacing poorly cooked midday meals with cake, biscuit, egg and milk; loan waiver up to Rs 1 lakh; favouring reservation for poor among other castes; and no more statues or museums.

Mayawati barely makes eye contact with the crowd during her 45-minute speech, at the end of which she picks up her handbag, goes backstage to have snacks, comes out 10 minutes later to meet each of the candidates and returns to the chopper. This is the routine at each of her rallies. The four-time chief minister addresses two rallies in a day, covering a district each, and returns to her Lucknow residence in the evening. Each candidate has a responsibility to bring in more than 20,000 people to the rallies.

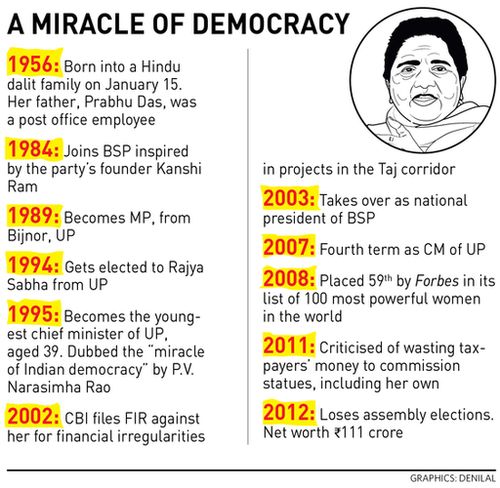

Mayawati is an enigma to most of her followers and rivals. Her rivals promote boisterousness in their rally crowds, she disciplines. Only approved slogans are allowed from the stage. Other parties issue manifestos to lure voters, BSP leaders say manifestos are mere documents; promises made by Mayawati in her speeches carry more weight and will be fulfilled. Mayawati likes playing the disruptor. Her rivals have forged new alliances and projected chief ministerial candidates, but the 61-year-old has been pinning her hopes on caste calculations and her past reign, which even her rivals agree ensured better law and order. At the heart of Mayawati’s strong pitch for the chief minister’s chair is the dalit-Muslim combination, with a 40 per cent voter share including 18 per cent dalits.

“The BSP has a core [dalit] vote that will not get divided. If the minority community also votes, together they can defeat the BJP. If they vote for the SP, the vote will get divided among factions led by Shivpal Yadav and Akhilesh, which in turn would help the BJP,” Mayawati tells the crowd, reminding them about the 400 communal riots that took place under the Akhilesh Yadav government’s watch. The BJP also wants to revoke the minority status of the Aligarh Muslim University and the Jamia Millia Islamia university, she declares.

The BSP is banking heavily on its dalit voter base. “I left my government job to join the BSP,” says Muzaffarnagar candidate Rakesh Sharma. “I would get core dalit votes, people from my own caste (Brahmin) would vote for me, too.” The party has roped in Afzal Siddiqui, son of Mayawati confidant Naseemuddin Siddiqui, to woo Muslims in Muzaffarnagar, which was worst hit by riots in 2013. He says those responsible for the riots should be held accountable. “If the BJP wins, then it will be a slap in the face of the rest of the Muslims.” he says. At the same public meeting, BSP zonal coordinator Naresh Gautam said, “I am pained your blood has cooled down after Muzaffarnagar. Remember the wound; we don’t have a stick, but you can vote.”

Muslims are central to the BSP’s attempt for power. Of its 403 candidates, 97 are Muslims. At neighbouring Deoband, home to Darul Uloom, South Asia’s largest Islamic seminary, the BSP has fielded multimillionaire Majid Ali, who has business interests and properties across the country. Called ‘Chairman’ by his supporters after his wife, Tasneem Bano, was elected chairperson of the zilla panchayat in Saharanpur, Ali says, “I will get votes from all communities. We believe in Mayawati’s strong administration.” Pitted against incumbent MLA Mavia Ali of the Congress, Majid will have his brother Kamaal R. Khan, the eccentric actor, campaign for him in the last few days before elections.

But who will the Muslim community vote for? Arshad Madani, head of Jamait-Ulema Hind, had appealed to Muslims to vote for the candidates of the Samajwadi Party or the BSP or the Congress to defeat the BJP, which is eyeing the non-Jatav dalit and non-Yadav OBC votes apart from its traditional upper caste base. Muslims, therefore, may go in for tactical voting, opting for the stronger candidate in each constituency.

On the road: BSP’s candidate Majid Ali (wearing a garland) campaigns in Deoband | Arvind Jain

On the road: BSP’s candidate Majid Ali (wearing a garland) campaigns in Deoband | Arvind Jain

But the alliance with the Congress has given the Samajwadi Party a slight edge over the BSP. “Mayawati has the arithmetic, but the circumstances have changed,” says a cleric from Darul Uloom. “This time, there are no communal overtones like in 2014. Public memory is short. Though riots had happened during the Samajwadi Party regime, Akhilesh was getting all the attention. The alliance with the Congress is helping them.” Also, Muslims are sceptical about the BSP’s dalit vote bank as many dalits had voted for the BJP in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. Moreover, unlike the Jatavs, who form the core of Mayawati’s dalit support, other dalit communities like the Valmikis are not averse to supporting the Samajwadi Party. “Akhilesh raised the salary of safai karamacharis from Rs 4,000 to Rs 15,000. We are indebted to him,” says Dalip in Muzaffarnagar.

Mayawati’s close aide Jagpal Singh, however, rubbishes claims of dalits deserting the BSP. “Even in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, we got nine lakh more votes than the 2012 assembly elections,” says Singh, a three-time MLA from Saharanpur. “How can anyone say we lost dalit votes? We will get votes from all communities.”

In an election that has been fought on caste and religious lines, what could, perhaps, boost the BSP’s poll prospects is the effect of demonetisation, which has been the great leveller across the country.