It is early evening in Bhatkal, a quiet coastal town in Karnataka. But the placidity is superficial; the ripples run deep here. Bhatkal rings a familiar note for those who have followed the birth of homegrown terror in India. It is home to Riyaz Bhatkal, Iqbal Shahbandri and Yasin Bhatkal, cofounders of the Indian Mujahideen, which has allegedly carried out a series of terror attacks in the country in the last decade. On December 19, Bhatkal was in news again after a special court of the National Investigation Agency (NIA) pronounced death sentence on Yasin Bhatkal alias Mohammed Ahmed Siddibapa and four others for carrying out twin explosions in Hyderabad’s Dilsukhnagar area on February 21, 2013. Eighteen people were killed and 131 people injured in the attack.

Yasin was a key link in the transition of the Pakistan-sponsored homegrown terror outfit IM to the global Islamic State. Arrested in 2013, Yasin told interrogators that some of the IM members—who had fled with him to Pakistan in 2008 after the Batla house encounter—had contacted Al Qaeda-Taliban leadership directly as they were unhappy with the control being exerted by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence. A few of them then formed Ansal ul Tawhid (AuT) to fight alongside the Taliban against the NATO forces. But as the IS brand grew bigger, they shifted base to Syria. This gave birth to the IS-India chapter, headed by Sultan and Shafi Armar, brothers from Bhatkal, who left for Syria in 2014.

According to investigators, Sultan, who was a close aide of IS chief Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, was killed in Syria. Shafi then took over the operations in India. The IS-India chapter has links reaching Syria and Afghanistan and the faces of this terror network are many, says the NIA—the nodal agency probing all IS cases in India. Fifty-four youngsters, hailing from cities like Mangalore, Bengaluru, Delhi, Mumbai, Lucknow and Hyderabad, have been arrested so far. In Kerala, 21 people have gone missing amid suspicion that they left to join IS (THE WEEK, November 13, 2016). The families of terror suspects and accused, therefore, are now under constant scanner.

For such families that carry the terror tag, daily life is a struggle and the wait for justice never ending. Take the case of Mohammed Safwan Armar, 28, youngest of the four Armar brothers. “I wanted to become an engineer. But when my brothers’ terror links started surfacing, I could not concentrate on my studies,” he says. “I dropped out of class 12 as I couldn’t clear the exams. All of a sudden I lost my childhood and my youth. Now I run a printing press in partnership with a friend.”

Safwan says Shafi worked in Dubai since 2007-2008, and the family lost touch with him in 2011-2012. “My eldest brother, Sultan, also lost contact with us around the same time. He was a maulvi and went to Deoband [in Uttar Pradesh] for two years. In 2008, he left for Muscat, where he used to deliver sermons. I don’t think they had any links with IS, but if they have done any wrong, the government is free to prosecute them,” he tells THE WEEK, sipping tea in a small tea shop.

Jihad has torn the Armar family apart. Only Safwan, his parents and Sultan’s eight-year-old son stay in Bhatkal. His third brother, Khalid, works in Dubai; he no longer visits India for fear of being grilled at the airports.

Mohammed Safwan Armar, brother of Shafi Armar, who heads the IS-India chapter | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Mohammed Safwan Armar, brother of Shafi Armar, who heads the IS-India chapter | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Then, there are families like those of Najmul Huda, 26, who has been charged with “conspiracy, recruitment, training, harbouring, membership and support to IS”. Najmul’s father, Saiful Huda, is a maulvi in Usmaniya Masjid in Permude in Mangalore. The family moved to Permude 45 years ago from a village in Uttar Pradesh, keen to give their children proper education. Despite the terror charges against his son, Saiful continues to teach young boys and girls in a madrassa. He just has one grudge. “The NIA officers told us they were watching our son for six months and arrested him just before he was about to carry out a terror strike. Why did they wait and watch?” asks Saiful. “Are they not guilty of allowing a crime to continue before them? Had they told us in the beginning that my son was going astray, I would have slapped him and put him on the right path. Today, it is too late. What did the NIA gain?”

Another IS terror accused, Delhi-based Mufti Abdul Sami Qasmi, has been charged with waging war and sedition after he was arrested in February 2016. According to the NIA, the fiery cleric attended meetings, delivered inflammatory speeches favouring the caliphate and Islamic State and encouraged Muslim youths to join IS. He is the first cleric to be arrested on terror charges. Sami owns two madrassas, one in Rampur and another in Patna. His wife, Dilshad Begum, is tired of doing the rounds of courts in Delhi to free her husband. “Who will listen to us? The media portrays him as a terrorist,” she says.

The IS propaganda is so strong, says an NIA sleuth, that it has influenced IT professionals like 25-year-old Abu Anas to sponsor travel of fellow radicalised youth to Syria by arranging for their visas to Turkey. A senior consultant in an IT company in Hyderabad, Anas was accused of spreading the IS net from Jaipur to Chennai via social media and acting as a financier for the outfit. His brother Abu Lehesin, 22, a B Tech student in Tonk, Rajasthan, finds time every weekend to visit him in the Delhi jail.

Back in the tiny lanes of Bhatkal, Gulshan Banu, mother of arrested IS operative Adnan Damudi, peeps out of her grilled door waiting for her son’s return. Adnan, a commerce graduate, was working at the World Trade Centre in Dubai, where his father, Mohammed Hussain Damudi, has been running a real estate business for the last 45 years. Adnan was deported to India in 2015 after spending six months in jail in Dubai. “The Dubai police were on the trail of the driver who used to drop Adnan home. One day, the police picked up both of them. Suddenly, we found out that he was being deported. The Indian agencies started calling him an IS operative,” says Banu. She has five other sons, the youngest is in class five; she is now worried about their future.

When THE WEEK reviewed the interrogation reports of new age jihadis, we found they had a common link—Shafi Armar and the use of social media platforms like Skype, Telegram, Facebook, Trillian, Surespot, WhatsApp, Hike and Twitter.

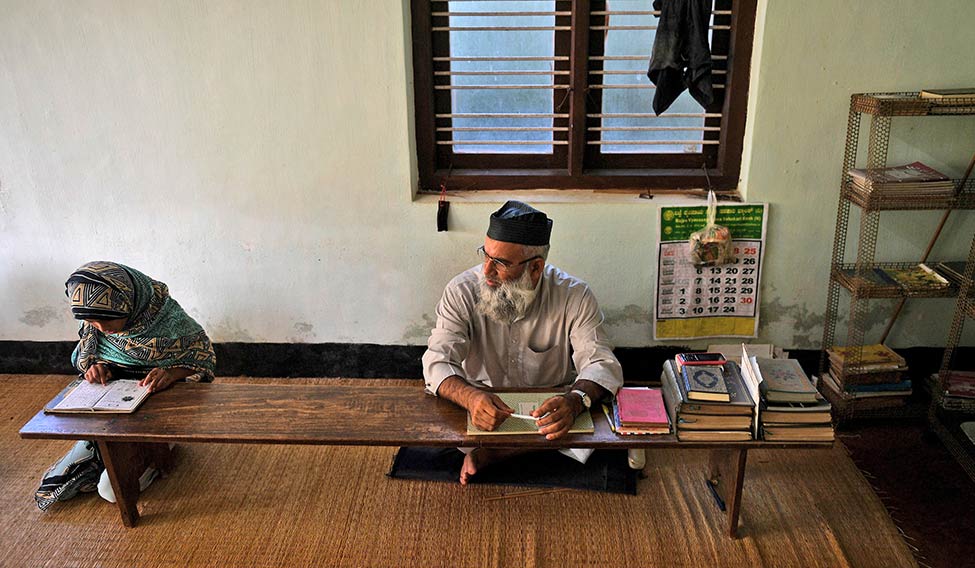

Harsh lessons: Saiful Huda, father of Najmul Huda, who was arrested in January 2016 by NIA, teaches at a madrassa in Mangalore | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Harsh lessons: Saiful Huda, father of Najmul Huda, who was arrested in January 2016 by NIA, teaches at a madrassa in Mangalore | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

The case of Asif Ali, 21, from Bengaluru is a classic example of how social media tools are being used by IS to spread its tentacles in India. During his interrogation, Asif told the NIA that he started using social media networks in mid-2011. His cousin created a Facebook account for him using a smartphone. His account’s password was his mobile number, which was also linked to his Telegram account. And it was in the virtual world that he first connected with Najmul Huda. Asif created a Trillian account in the name Asif Hindi in July 2015 on Najmul’s direction so that he could chat with associates from Bengaluru, Tumkur and Hyderabad without leaving any trail for the law enforcement agencies. The January 2016 crackdown on IS in five states saw the arrests of Najmul, Asif and others. Asif’s father, Jagir Hussain, says his son was into stone polishing business and that they found nothing suspicious in his behaviour.

In Bhatkal, the families of IM terror suspects are still waiting for their cases to come to a logical conclusion. One such family is of Abdul Wahid Siddibapa, the suspected financier of July 13, 2011 Mumbai blasts, who was detained in Dubai in 2014. His wife, Fauqiya, and three children now live with her father, Mansoor. “I have spent all my money and jewellery trying to fight his case. I had a miscarriage due to stress. Will the NIA or Mumbai ATS compensate for the loss?” she asks. Mansoor gathers news clippings which say that his son-in-law will be let off as the agencies have found no evidence against him.

Fauqiya can still meet her husband in jail. The wife of another IM terror suspect, Dr Mohammed Afaque, isn’t as lucky. Afaque’s wife, Arsala, hails from Pakistan. Afaque and his cousin Abdul Suboor are accused of supplying explosives for the 2011 Mumbai blasts, the failed Pune blasts of August 1, 2012 and the 2013 Dilsukhnagar blasts. “Afaque used to fight for people’s rights against the police and file RTIs [right to information petitions]. The police claimed a huge cache of explosives had been recovered from him but there is no evidence,” Afaque’s brother and lawyer Sayed Imran Ahmad told THE WEEK.

Mansoor with daughter Fauqiya, wife of Abdul Wahid Siddibapa , a suspect in the July 13, 2011 Mumbai serial blasts | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Mansoor with daughter Fauqiya, wife of Abdul Wahid Siddibapa , a suspect in the July 13, 2011 Mumbai serial blasts | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

In Bhatkal, Dr M.M. Haneef Shabab, convener of the media watch committee of Majlis-e-Islah wa Tanzeem, a sociopolitical organisation, says there is a deliberate attempt in the country to stoke communal discord. “We keep giving memos to political leaders,” he says. “Just before Eid, the BJP MP from Mysore, Pratap Simha, organised a BJP Yuva Morcha rally in Bhatkal. Why did he choose Bhatkal? When meat will be cooked and served in houses during the festival, organising a rally of hindutva activists is calling for trouble. But nobody listens to us. When there is a conflagration, they will accuse Muslims of communal disharmony.”

Veerandra Shanbagh, principal of Shri Guru Sudhindra College in Bhatkal, says no government should play politics over terror. “My students are so scared. When they go anywhere, they don’t say they are from Bhatkal. They say they are from Murudeshwar (a nearby town). When Bhatkal is not the surname of any of the arrested accused, why do the agencies put it as their last name?” he asks.

Says Yasin’s uncle Yaqoob Siddibapa: “No one by the name of Yasin Bhatkal exists. The name Yasin Bhatkal has mischievously been given by the Indian agencies. We believe Ahmed Siddibapa [Yasin] is innocent and we will appeal in the higher court against the NIA court verdict. He had even asked for law books which he was studying when he was in jail so that he could defend himself better.”

The car outside Yasin’s house, which drew international attention following his arrest and deportation from Nepal in 2013, gathers dust, but the dust around Bhatkal’s terror connect won’t be settling anytime soon.