Two years ago, Siddharth Srivastava, a 40-year-old IT professional, was admitted to a hospital in West Delhi. He was diagnosed with a severe case of malaria. He had come to the hospital seven days after developing fever. By that time, the malaria parasite had invaded most of his red blood cells.

Within a few hours of hospitalisation, his kidneys began to fail. By evening, he had gone into a shock—a life-threatening condition in which reduced blood supply causes organ failure. By afternoon the following day, malaria had affected his brain. Srivastava died on the third day of his hospitalisation.

His wife, Soumya, is yet to recover from the tragedy. She just cannot come to terms with the fact that it was malaria, known to be a treatable disease, that took her husband’s life.

Malaria is killing thousands of people every year in India. “It [the risk of death] largely depends on the parasite load in the patient’s blood, the patient’s immunity and the gap between the onset of infection and drug delivery,” said Dr Jagdeep Chugh, senior consultant at Fortis Hospital in Delhi.

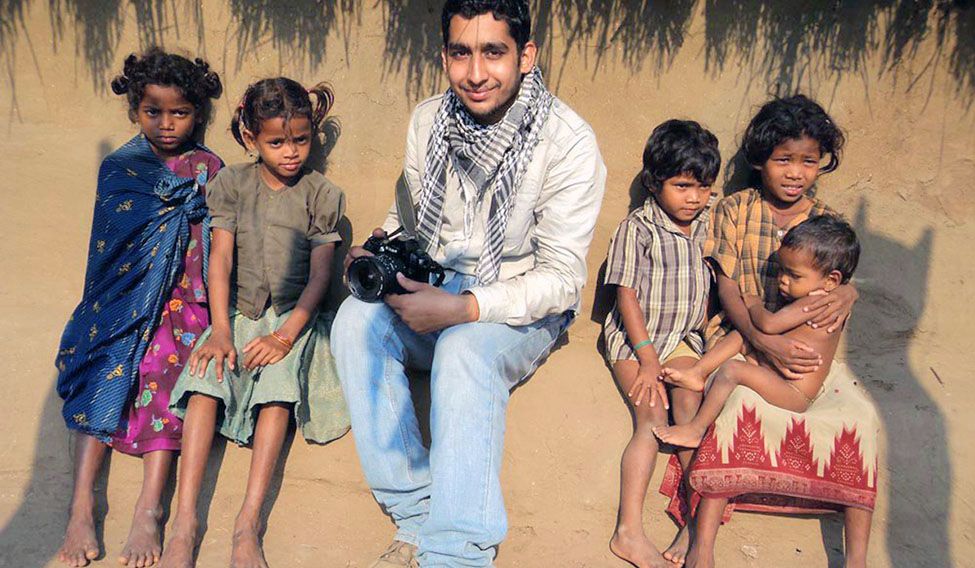

Three years ago, photojournalist Tarun Sehrawat, 23, went to a Maoist-affected area in Chhattisgarh to cover a story with his colleague. They were cautious while dealing with Maoists, but they could not identify the hidden threat of malaria, which was prevalent in the region. Tarun succumbed to malaria soon after he returned to Delhi after the assignment. His colleague survived the infection.

Doctors say malaria is still rampant in urban and rural areas of the country. “In rural India, the incidence of malaria is so high that if each and every case gets reported, the disease would have to be declared as an epidemic,” said Dr S.J. Subanna of the NGO Lepra—Health in Action. “In these areas, if a patient comes to us with high fever, we prescribe antimalarials even before we send her blood sample for tests. But not all the people suffering from fever come to a doctor. They rely more on traditional healers. They come to a clinic only when their condition deteriorates.”

The situation is the same in the tribal belts of Gujarat, Maharashtra and Kerala. Lancy Lobo, director of Centre for Culture and Development in Vadodara, described in his book Malaria in the Social Context the attitude of villagers in Gujarat towards malaria and other diseases. “People in the tribal, hilly region of Surat still believe that fever occurs when a person is possessed by a spirit and thus needs supernatural intervention. Government has a lot to do to make these people understand the importance of medicines,” said Lobo.

The factors behind the prevalence of malaria in urban India are different. “People treat any fever as viral fever for the first three days. Even after three days, in most cases, doctors add an antibiotic to rule out bacterial infection. They think about malaria only after the sixth or seventh day of fever,” said Chugh.

When seven-year-old Namita Singh of Delhi had high fever last year, her father took her to a doctor, who prescribed a few medicines. It was only on the 10th day of fever that the doctor advised her father to take her to a hospital. By that time, malaria had affected her kidney and brain functions. When she did not respond to treatment, she was referred to BLK Hospital, where she was put on ventilator for 10 days. Fortunately, Namita survived the scare. “She was in a bad state. There were multiple complications; we could have lost her,” said Dr J.S. Bhasin of BLK Hospital.

In Mumbai, monsoons come with a flood of malaria cases. Dr Pradip Shah, head of the department of internal medicine at Fortis Hospital in Mulund, said hospitals were swamped by malaria cases two weeks after the rains. Fortis itself admits more than 100 malaria patients a month during monsoons. And there are at least two hundred outpatients in the same period.

According to Shah, the resistance to chloroquine has increased from 20 to 60 per cent in the past five years. Plasmodium vivax, which causes a comparatively milder form of malaria that is usually not fatal, now manifests itself in a much virulent form. “Vivax now causes cerebral complications and leads to death in some cases. In fact, we also see patients suffering from both kinds of malaria—falciparum as well as vivax,” said Shah.

One of his patients, Siddhamma Solapure, 66, was diagnosed with vivax malaria. For three days before she came to Fortis, she was under the treatment of a neighbourhood doctor, who tested her for malaria. Since the test result was negative, she was prescribed a strong antibiotic and saline transfusions.

When she was finally brought to Shah, her platelet count was 80,000—well below normal. “Malaria is so rampant here that almost all of us in the family have contracted it. I, too, suffered from malaria and dengue three years ago,” said Siddamma’s son Suryakant Solapure, 39, who works as an accountant in Mumbai.

Diagnosis of malaria depends more on the clinical competence of a doctor than on blood and advanced antigen tests. Even a lab technician has to be competent to diagnose malaria at an early stage, when there are very few parasites in the blood.

The treatment should be as per the guidelines issued by the World Health Organization. The dosage of antimalarials has to be accurate not just for effective treatment, but also to prevent the parasite from developing resistance. “If cases of resistant malaria multiply, we would be in a difficult situation,” said Shah.

What prevents malaria eradication in India, say doctors, is the fact that the government does not even accept the extent of the problem. Malaria cases and deaths in the country are grossly underreported. According to researchers at the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, as many as 46,970 Indians died of malaria in 2010 alone. But the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme says only 1,023 people died of malaria that year.

A 16-member committee of the Indian Council of Medical Research has found that the number of malaria deaths in India on an average would be around 40,297 a year, nearly 40 times the present estimate. In fact, doctors say there are about 200 districts where the number of malaria cases has reached epidemic proportions.