In Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand’s stupid novel of epic proportions, John Galt invents a motor that runs on air. Hot air! No physics.

But an Israeli company, Water-Gen, has built a machine that produces water from air—cold air. And good physics. The machine sucks in air from around it, and cools it to produce water, just like cold wind blows on clouds and makes rain. It runs on little electricity, and is already installed in the Israeli embassy in Delhi. Maxim Pasik, Water-Gen’s executive chairman, thinks it has huge potential in India. “We will soon install one on pilot basis at Delhi’s Connaught Place,” he said.

The machine comes in three sizes—a small one for homes, which can make 20 litres a day (30 in India, where the air is humid); another that makes 600 litres a day for schools; and a third that makes 5,000 litres a day for townships.

With no piping or pumping—and just connected to a simple power plug—the machine’s water will cost Rs 1.6 per litre (at current rates). “The other beauty is that it doesn’t need maintenance—just change the filter once a year,” said Michael Rutman, a director of Water-Gen.

Israel has many such wizardries to offer India, which the more advanced western world does not have. The reason is simple. Western technologies are based on abundance of resources, whereas Israeli technologies presuppose scarcity of resources. The desert country gets hardly a week’s rain a year, and has only two small barrages and no dams, but it exports tomatoes and flowers to Europe and peppers to the rest of the world.

The trick is not just drip irrigation; the Israelis even have sensors that find out when a plant is thirsty and wet its bed—the plant bed. Half the water that Israelis drink and use in farms is desalinated sea water; 80 per cent of the water, including sewage, is recycled.

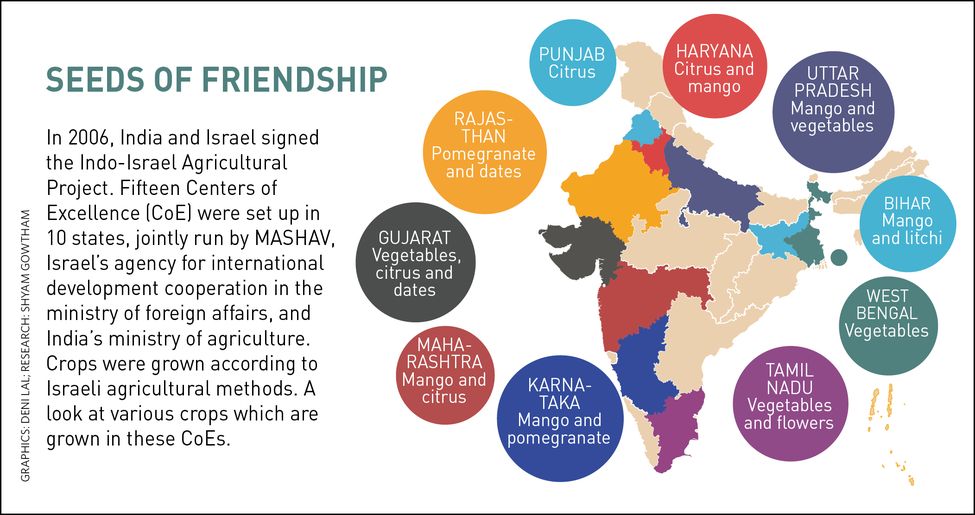

Israel is already big in India’s farms, having opened 15 centres of excellence in India in agriculture, horticulture and micro-irrigation. Another 11 will be opened to train farmers in better practices.

Israel’s cows, fed on pomegranate peels, yield 40 litres a day—three times more than the best Indian cow. Cowsheds have sensors that guide cows into and away from the sun. Israel’s vets have found that too much exposure to the sun reduces yield.

Most of the power is from the sun, yet Israelis do not waste it. Lights in the government press office rooms go off when there is no movement for more than a few minutes; sensors detect human presence and switch lights on or off. Tel Aviv University has high-ceiling halls, but the air-conditioning, from the floor, works only up to six feet. It is simple physics that hot air goes up; it is smart engineering to cool the room from the floor.

Military commanders throughout history have insisted on economy of firepower; Israelis have technologies even for that. Hamas had been shooting rockets in thousands, and Israel developed missiles that anticipate the trajectory of the incoming rockets and fire at them. If an incoming rocket is expected to land in an open area, the launchers would just let the rocket land and ‘waste its fire in the desert air’. Engineers have also developed radars that detect tunnels dug by Hamas insurgents; archaeologists use the same radars to dig out ancient cities in Jerusalem, Jericho and elsewhere.

Israel leads in health care, not with expensive hospital machinery that the west sells, but with smart little gadgetry that makes health care cheap. Researchers have developed a kit that nurses can carry in their bags and detects cyst in the wombs of village women. The device looks for unusual hair growth on a woman’s face—a sign of cyst growth.

Israeli innovators are ready to partner with India to upscale such technologies. “Israel can be the lab, and India the factory,” said Anat Bernstein-Reich, president of Israel-India Friendship Society, who believes that Israel can help India in water technologies, agriculture, irrigation, smart cities (Tel Aviv is rated as one of the world’s smartest cities), health care and more.

The big business with India is now in two Ds—defence and diamonds. Without defence, trade has been only $4.5 billion a year, half of which is made up by diamonds that are traded both ways: uncut to India, and cut diamonds back to Israel. Export—minus the two Ds—amounted to just $1.15 billion last year, of which 80 per cent was telecom goods and electronics. India’s export to Israel, minus the diamonds, amounted to a paltry $800 million, mostly chemicals, textiles, plastics and rubber.

India figures in three shapes on the Israeli business radar. The first is as a market, one of the world’s largest, and one which would need Israel’s ‘little’ technologies. The second is as a factory, where the technologies developed in Israel can be manufactured to scale. This fits in well with Narendra Modi’s Make in India. Moreover, Israel views itself as a startup nation, and its manufacturing economy is run largely by startups. Modi’s Startup India thus excites Israelis.

One problem area is India’s outmoded patent laws. Israelis jealously guard their intellectual property, much more than the westerners do. Bernstein-Reich, who is also a lawyer, wants India to make its patent laws stricter. “India’s IP regime makes Israeli businessmen nervous,” she said. “We want the laws, and the law enforcement, to be stricter.”

A third potential of India is as a conduit to the Arab world. Since Arab states do not have diplomatic or trade ties with Israel, Israeli traders see India, which has business and labour contacts with the rich Arabs, as a bridge. “There is no untouchability about technologies,” quipped an Israeli diplomat. “They do buy our stuff through third countries. India can be one big third country.” But the lack of a free trade pact with India is a barrier.

Indian companies have started investing in Israel. Jain Irrigation has bought Israel’s NaanDan, Triveni Engineering has invested in Aqwise, and Sun Pharma acquired controlling stakes in Taro Pharmaceuticals. Tata Consultancy Services, Wipro, TechMahindra and Infosys are already there, as is State Bank of India.

Another area, which Israelis are a little reluctant to talk about, is the labour market. Though machines do a lot of jobs, Israel needs more people, too. Workers come in thousands from Thailand, but Israelis think that Indians, who speak English, could replace them. There are only 12,500 Indian citizens in Israel, most of them nurses and other hospital hands from Kerala, a few diamond traders from Gujarat and techies from all over.

Israelis believe that the fondness that the cultures have for each other should help businesses click. About 40,000 Israelis visit India every year; almost every youth wants to go to India for shalom and shanti on the banks of the Ganga or the lakeside of Pushkar, after his compulsory military service.

The Indian Hospice in Jerusalem, started by Sufi saint Baba Farid from Punjab, soon after Sultan Saladin and King Richard left after the third crusade 800 years ago, is a legend of fortitude in the strife-torn city. Even when the city’s control changed hands several times during the 20th century, it survived as a beacon of peace and compassion, and is still run by the descendants of the baba.

Every Israeli who meets an Indian talks of how well India had treated its Jews, unlike how Europe had. “It is almost a folklore here—how we were treated as the nobility there,” said Yoel Elias, a Cochini Jew. There are about 85,000 Indian-origin Jews, 4,000 of who are expected to throng the Tel Aviv Exhibition Ground to listen to Modi. The majority are the Bene Israelis from Mumbai, many of who still speak a creole of Marathi, Hindi and Hebrew, followed by the Baghdadi Jews from Kolkata and the highly-regarded, but fewer Cochini Jews, who have their Malayalam songs, stories, appams and distinct rituals. Of late, a Mizo tribe has been recognised as a long-lost Jew tribe and its people have started migrating.

Eliyahu Bezalel, who hails from Chennamangalam near Kochi, is regarded as Israel’s foremost farm scientist; India honoured him with Pravasi Samman in 2005. Sheikh Ansari, who runs the Indian Hospice in Jerusalem, was honoured in 2011, and cardiothoracic surgeon Lael Anson Best in 2017.

Most Israeli universities have collaborations with Indian universities, not only in technology disciplines but also in humanities. President Reuven Rivlin’s visit to India last year saw the signing of 21 memorandums of understanding in education. Tel Aviv University has nearly 100 Indian postgraduate students.