The day a soldier has to demand his dues will be a sad day for Magadha. For then, you will have lost all moral sanction to be king.

From Kautilya’s letter to Chandragupta Maurya

Wing Commander M.M.S. Paintal leads a comfortable retired life in Vadodara. The former fighter pilot, after a glorious career in the Indian Air Force starting with the 1965 war, passively followed the One Rank, One Pension agitation through television, newspapers and WhatApp updates—till August 14, 2015, when he saw veterans who were on fast at Delhi’s Jantar Mantar being hauled up by the police. Something snapped. “I just knew that I was needed there,” he says.

Paintal found himself heading for Delhi with just a bundle of clothes and a one-way ticket. He now handles the media cell of the United Front of Ex-Servicemen, an umbrella body of 40 ex-servicemen organisations across the country, which is spearheading the demand for OROP. As he patiently explains the nuances of the complicated pension issue of military veterans, he says, “I don’t know when I will return, but it won’t be without OROP. If the government does not give it to us, we will snatch it eventually. But, a fauji does not back out.” He spends his nights at the homes of various course mates across the city.

Mild-mannered, former Indian Navy Commander A.K. Sharma, 67, got really angry when he saw the television visuals on August 14. A regular at Jantar Mantar since the veterans first sat there over 80 days ago, Sharma decided on August 26 to park himself in the FUD (fast unto death) tent. Ever since, he is sustaining on tulsi and cumin water.

Speaking to the FUD men is not easy—retired military wives, who are at the venue in full force, frown upon any effort that expends the diminishing energy reserves of these senior citizens. But, Sharma gives a weak grin and says, “I just knew I had to be here. Look at my friend here, Havildar Major Singh; he has been fasting for 19 days. He has been to hospital and back, but his fast is unbroken.” Sharma’s daughter, an interior designer, sits nearby, chanting prayers. Post retirement, the officer and men lines are blurred.

In another pandal, the number of veterans and “veer naaris” (wives and widows of ex-servicemen) who are on relay fast swells by the day. An agitation finishing its third month soon is expected to flag in enthusiasm. But, here, the outrage increases and the resolve gets strengthened with every insensitive political utterance. Like when Finance Minister Arun Jaitley said that yearly revision of pensions was not possible. “It is not OROP then! It will be One rank, Multiple Pensions again,” says Col Tekpal Singh, formerly with the 16 Madras Regiment.

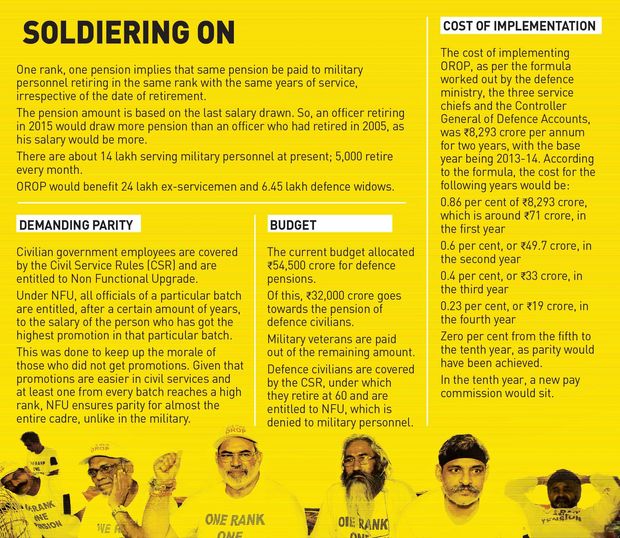

Graphics: Binesh Sreedharan

Graphics: Binesh Sreedharan

On the surface, the scene at Jantar Mantar looks like a cross between a regimental raising day barakhana, an army wives’ welfare meet and a reunion of former course mates. Many men wear their service medals proudly. There is a colourful assortment of regimental and ship caps on display. Gurdwara Bangla Sahib sponsors meals; many veterans sponsor chai and other expenses. Money for the campaign comes openly from veterans, and quietly from serving men. Every day, there is a star attraction. Actor Nafisa Ali, a regular, introduces herself as “Col Sodhi’s wife”. Then there was Rajalakshmi Ramachandran, 86—wife of a major, mother to three retired officers and mother-in-law to one—who has come from Bengaluru. “I wanted to be in the FUD tent, but my health does not permit,” she rued.

But, rub your eyes, look at the same scene, and you see something pathetic and heartrending. These are men who, after a lifetime of braving bullets and inhospitable terrain, have retired to find themselves foxed by the government, and how. Proud shoulders stoop in dejection, veined and gnarled arms brandish black ribbons of protest.

OROP is not a new issue; its genesis goes back to the afterglow of the 1971 war, when “we were first backstabbed”, as double Vir Chakra awardee Wing Commander Vinod Nebb puts it. The Third Pay Commission of 1973 cut military pensions from 70 per cent of last salary to 50 per cent. A full pension comes after 33 years of service, which civilians get, but few soldiers get, as they retire early to keep the force young. To counter the anomaly, the government proposed OROP, a promise subsequent governments have successfully managed to renege on.

Octogenarian Col Inderjit Singh is one of the pioneers in the OROP crusade, having started agitation way back in 1982 after forming the All India Ex-Servicemen Association. He has met every prime minister from Indira Gandhi to Manmohan Singh, been part of several committees to discuss OROP, led several agitations outside Red Fort, Boat Club and Jantar Mantar. “On several occasions we were on the brink of getting OROP, but it never happened,” he says.

Two days after he submitted his report to Indira Gandhi, she was assassinated. V.P. Singh was removed as defence minister over the Bofors scam just when the Rajiv Gandhi government seemed ready to clear OROP. Other governments promised, but dithered in implementing. The Fifth Pay Commission accepted OROP, but during implementation made it into modified parity. “We protested for 107 days at Red Fort, 23 former service chiefs wrote to the government and on November 2, 1997, the defence secretary accepted OROP. But then the I.K. Gujral government fell and the issue went to the back-burner again,” says the wheelchair-bound colonel, who attends the Jantar Mantar protest every day. Isn’t he tired? “A soldier fights to the end,” he states.

So, what is different this time? It is the callous way in which Narendra Modi took them for a ride that has “hurt, humiliated and infuriated us”, says Maj Gen Satbir Singh, who is leading the agitation. It all harks back to the promise Modi made in Rewari in 2013. “Now, when it comes to fulfilling the promise, he backs out, citing financial reasons,” growls Col A.K. Kaul, an IPKF veteran with 80 per cent disability. “Are we trade unions that they are negotiating our demands?”

Used to straight talk, soldiers find the duplicity appalling. Remarks from the government like, “a few modalities have to be ironed out” or “the financial implications are high” or “OROP is difficult in arithmetical translation” and, worse, “the para military forces will demand the same”, stoke their fury further.

The United Progressive Alliance had accepted OROP, and the Koshyari committee had defined what OROP entailed. “We are only asking them to implement what they approved,” said Satbir Singh. “They defined OROP, they must have considered the financial implications,” says Sharma. “For us now, it is not so much a matter of money as it is of honour and self-respect. If the paramilitary demands OROP, it is a different issue. It has neither been promised nor approved for them. Here, it only has to be implemented, it is already approved.”

Indeed, there will not be bonanzas as many are saying. A sepoy, who retired after 17 years of service before 2006, gets a pension of Rs.5,196; post OROP he will get Rs.7,605. A pre-2006 retired officer drawing Rs.30,350 will get Rs.39,500; a sepoy’s war widow getting Rs.3,500 will get Rs.5,000.

The defence ministry sent its recommendations to the finance ministry in March, in which it had fully accepted the principle of OROP. But, it kept getting the file back from there over the issues of financial liability and the periodicity of revision of pensions, sources said.

The OROP fight grew stronger after the Sixth Pay Commission introduced Non-Functional Upgrade (NFU) for civilians (see graphics). Simply put, under NFU, even without promotion, every bureaucrat will at least draw the salary of a joint secretary (equivalent to rear admiral/ major general), while timescale officers can at best get the salary of a colonel, two ranks lower.

Soldiers are also angry at the political mileage people are trying to make from their agitation. Congress vice president Rahul Gandhi was unceremoniously asked to go away when he came for a photo-op visit. Ace lawyer Ram Jethmalani addressed the gathering another day. The veterans politely heard him out and his visit went unreported by the media.

As the standoff inches towards its fourth month, the government is keen on a settlement. Already, protesting ex-servicemen have taken to Twitter to blame Modi personally for the police action on August 14. The indefinite hunger strikes of an increasing number of veterans are another cause for concern. “God forbid, if anything happens to even one of them, the government will face a wrath it has not even imagined,” forecasts Kaul. Among officers in service, too, is the rumble that perhaps some unit may rebel if a veteran loses his life. “If they implement OROP in toto, they incur expense, but get our goodwill. A partial implementation will also incur an expense, but no goodwill. So, the government gains nothing,” reasons Kaul.

The government, meanwhile, has been meeting representatives of People Below Officer Rank (PBOR) or jawans, a ploy that has caused a faction of PBORs to break away from the main agitation. Their grievance is the difference in emoluments between officers and jawans, though they face same risk to life. The chants of “Afsar log, murdabad” rent the air even as the others shout slogans demanding OROP.

Over the years, one of the objections from the finance ministry officers is why officers, most of whom retire at around 54 to 56, should benefit from a scheme that was formulated mainly to address the truncated years of service of a jawan, who retires between 35 and 38.

Now, with the Rashtriya Swayam-sevak Sangh demanding that the government resolve the issue, the government has roped in Principal Secretary Nripendra Misra and National Security Adviser Ajit Doval. It looks as if the solution is in sight, but the faujis have seen many false dawns. This time, they are not keen to buy into another achche din.

Sources close to Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar say that Modi’s poll promise was like a father promising a motorcycle to a 16-year-old son, if he scored well in the exams. “It’s difficult to keep such a promise, but we will have to honour the commitment Modi made,” says the source. Only time will tell whether Modi’s commitments are like Salman Khan’s, whose dialogue in Wanted has become the pop epitome of commitment: Once I make a commitment, I don’t even heed my own objections.