In April 2007, the small Baltic country of Estonia witnessed a series of cyberattacks that knocked out websites of its government, political parties, newspapers, corporates and banks. The timing of the attacks, which were later found to be coordinated, was interesting: It happened at a time when Estonia was embroiled in a dispute with Russia over the relocation of a World War II memorial in Tallinn, its capital. It was their worst bilateral dispute since the fall of the Soviet Union.

The attacks went on for three weeks, and Estonia alleged that the Kremlin was behind them. It was the first time a country was openly declaring itself as a victim of state-sponsored cyberattack. NATO, of which Estonia has been a member since 2004, dispatched its top cyber experts to trace the hackers and beef up the country’s e-defences.

Estonia learnt its lesson. Nearly a decade after the attacks, its cybersecurity apparatus is one of the world’s finest. And Tallinn, a startup paradise known as the Silicon Valley of Europe, is home to the NATO Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence.

Estonia served as an eyeopener for many countries, but not India. In a neighbourhood where traditional threats continue to chip away at its defence resources, India is yet to fully wake up to the dangers of cyberattacks.

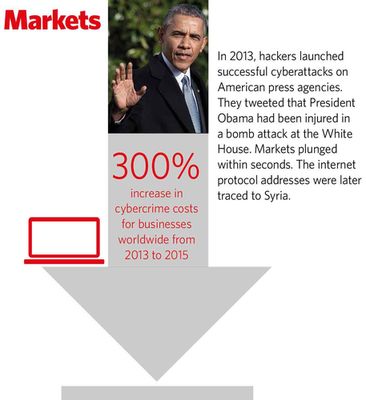

The latest alarm call is the Intelligence Bureau’s security audit of around 6,000 computers in various departments, including the ministries of defence and external affairs. Carried out over the past five years, the audit revealed that one-fourth of the sensitive sectors of the Union government are under incessant attack. “It has been noticed that 25 per cent of the attacks were against the defence ministry,” said the report, which was accessed by THE WEEK.

Lost and not found: Sanjay Dhande and his wife, Medha, lost Rs19 lakh after their bank account was hacked | Kedar Bhat

Lost and not found: Sanjay Dhande and his wife, Medha, lost Rs19 lakh after their bank account was hacked | Kedar Bhat

The worry, said the report, was not just about Beijing or Islamabad mounting a cyber offensive, but also about a “man with a machine” in any part of the world worming his way into the country’s electronic systems. With the Narendra Modi government laying emphasis on projects such as Digital India and Smart Cities Mission, which rely on electronic infrastructure to store, retrieve and manage data, securing the country’s e-defences has become crucial.

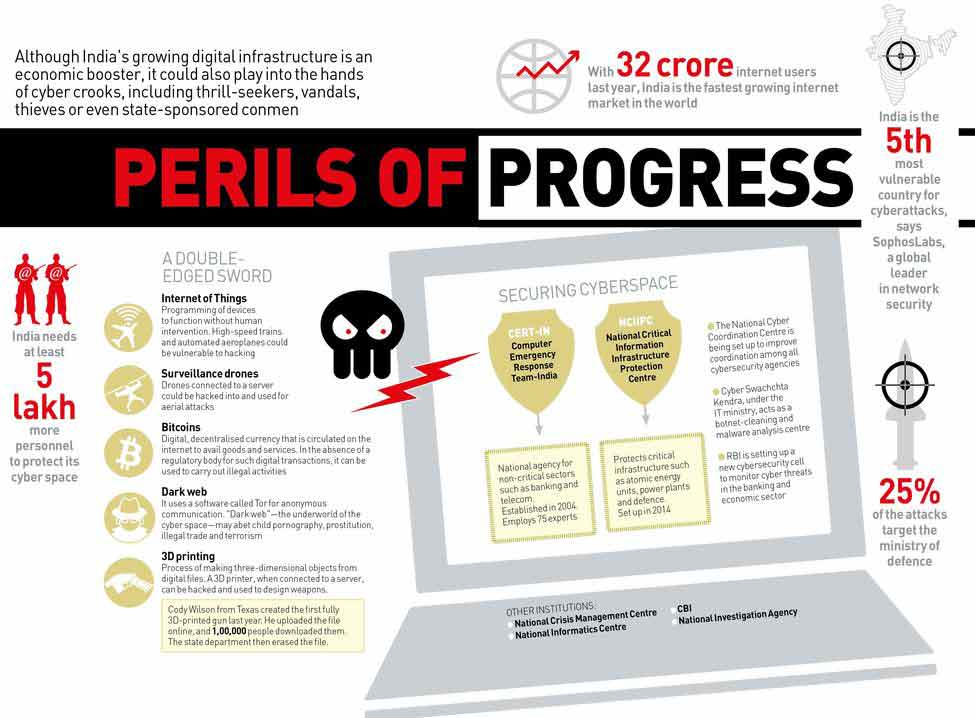

What is particularly alarming is the rising volume and frequency of cyberattacks. The Computer Emergency Response Team-India (CERT-IN), the nodal body for handling cyberthreats which was established in 2004, has handled 54,483 security incidents so far. In 2015 alone, CERT-IN handled 49,455 security incidents, including malware propagation and hacking and defacement of government websites.

CERT-IN has a 24x7 control room comprising 75 tech experts. It was set up in 2010, when coordinated attacks tried to sabotage the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi. The cyber warriors of the People’s Liberation Army were thought to be behind the attacks, which averaged 200 a day. Their aim: bring down the entire electronic system that helped organise events, sell tickets and arrange the movement of teams and delegates.

“If any system was compromised, it could have resulted in complete chaos, created a huge security scare and showed India in poor light,” said G.K. Pillai, who, as home secretary, oversaw the preparations for the games.

Jolted out of its inaction, the government proposed to set up a National Cyber Coordination Centre to improve coordination between the Centre, states and various other stakeholders. Six years later, the NCCC continues to be plagued by bureaucratic and procedural hurdles. The Modi government is now trying to fast-track the process of making it operational.

India has developed a graded mechanism to fight cyberattacks. Level one attacks constitute a focused attack on a single entity; level two involves an attack on two institutions; level three targets multiple institutions; and level four threatens national security.

CERT-IN handles attacks up to level three. Level four attacks come under the purview of the National Crisis Management Centre, headed by the cabinet secretary. It is up to the NCMC to coordinate countermeasures and secure international cooperation in case of a breach. At the top of the cybersecurity pyramid is Arvind Gupta, deputy national security adviser.

One of the sectors most vulnerable to cyberattacks is banking. Last year, CERT-IN warded off a “ransomware attack” on two Indian banks. A ransomware is a malicious software designed to bring down an electronic system if the ransom is not paid. CERT-IN not only alerted the banks to the threat, but also took the help of internet service providers to prevent the attack. The names of the banks have not been revealed.

Banks in India have been on alert especially after February this year, when hackers infiltrated the system of Bangladesh Bank, the central bank of Bangladesh, and issued payment orders via the SWIFT network to steal $951 million. The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, or SWIFT, is an international network that enables financial institutions to send and receive information about transactions across the globe. The hackers sent 35 payment orders, five of which were granted, resulting in a loss of $101 million. The perpetrators have not been tracked.

Taking heed, the Reserve Bank of India is in the process of setting up a cybersecurity cell exclusively dedicated to monitoring cyberthreats in the banking world.

Unlike in Estonia’s case, India has witnessed only stray attacks. The gravest among them, perhaps, was an incident at Terminal 3 of the Indira Gandhi International Airport in Delhi on June 29, 2011, in which the common users passengers processing system (CUPPS) was disabled.

Deactivate CUPPS, and flight operations can go haywire. Suppose you are a passenger entering the terminal. You approach a check-in counter of a particular airline, and the agent verifies your booking and makes an entry of your arrival. The entry is then transmitted to the airline’s host computer using CUPPS.

A CBI inquiry into the disabling of CUPPS at the Delhi airport led to a disgruntled employee, who had accessed the system without authorisation. The employee had introduced a malicious script that deleted registry keys and affected critical system files.

For security agencies, this incident exemplifies their biggest concern—the danger of systems being hacked into to cause havoc. An immediate worry is the vulnerability of railways and high-speed trains, so much so that the government is mulling the inclusion of railways in the list of critical information infrastructure whose security is entrusted with the National Technical Research Organisation, a technical intelligence agency under the Prime Minister’s Office.

Delhi Metro Rail Corporation is a fine example of how to protect automated systems. “All critical systems, like signalling, communication and ticketing, operate on DMRC’s internal network,” said Anuj Dayal, the corporation’s chief public relations officer. “They are centrally controlled…. To ensure safety of systems, USB ports and CDs are disabled. Physical security of the systems is guarded through limited access to authorised personnel, and the systems are password protected.”

Kiren Rijiju, minister of state for home, said India needed to invest more in resources and structural setups. “We must have a robust coordination network in place between various agencies, stakeholders and countries,” he told THE WEEK. “Cyberthreats are not country-bound, so we need a combined effort from all likeminded countries.”

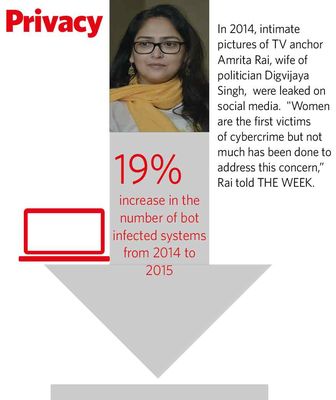

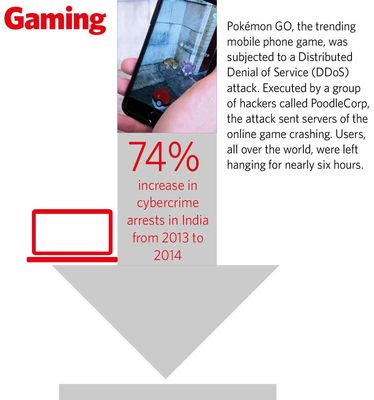

According to Muktesh Chander, director-general of Goa Police, the need of the hour is better awareness and better cybersecurity practices in governments, corporations and homes. And, of course, stringent laws. Despite growing threats, the number of cyber-related cases registered in the country remains low. According to the government, 7,201 cybercrime cases were registered in 2014. But, the same year, as many as 25,037 Indian websites were defaced and 77,28,408 bot-infected systems were tracked.

According to a top police officer, herein lies a huge discrepancy. “For each case of defacement of a website or an infected system, there should be a corresponding case registered with the police,” said the officer. “It is surprising that only 7,000-odd cybercrime cases were registered in 2014.”

The government has not been able to wrap up even exisiting cases. Take the case of Prof Sanjay Govind Dhande, former director of IIT Kanpur and member of the prime minister’s scientific advisory council. On September 10, 2013, Dhande’s wife, Medha, got a call from a leading bank’s Aundh branch in Mumbai, asking whether she had withdrawn around Rs 19 lakh from her account. Medha had not, and was shocked.

The Dhandes lodged a complaint with the police on September 14. On September 26, they also filed a complaint before the adjudicating officer at the department of electronics and information technology, under various sections of the Information Technology Act, 2000.

Investigations revealed that the bank account was linked with a phone number used by Medha, on which she used to receive confirmation of all deposits and withdrawals. The number, and her phone, had stopped functioning on the afternoon of September 6. When she contacted the telecom service provider, she was told to get her sim replaced.

As the succeeding days were holidays, they were able to contact the telecom provider only on September 10. But, despite being issued a new sim, the calls to the number were getting diverted. Medha contacted the provider again. It corrected the database and the phone started working properly on the evening of September 10. That was when she got the call from the bank.

“A duplicate sim of Medha’s number was issued in Nagpur on the basis of forged papers,” Dhande told THE WEEK. “The fraudster had submitted a copy of a passport, which had photo of Dayanidhi Maran, then IT minister. On it, however, the gender was marked as female. When large withdrawals were made, the alerts were received on the duplicate sim.”

Dhande’s lawyer Prashant Mali said the investigators were yet to catch the culprits and find out how the bank account got compromised. On January 16, 2014, Dhande got a court order in favour of him getting compensated, but the bank moved the Cyber Appellate Tribunal in Delhi. “Since the post of the chairperson of the tribunal has been vacant since June 30, 2011, the appeal has not been heard till date,” said Mali. Dhande is among 70 persons whose appeals are pending before the tribunal. Every few months, the 68-year-old visits Delhi in the hope of getting his case heard. The wait, however, could well be unending. “It [the tribunal] is a defunct body right now,” said an official on condition of anonymity. “Till a chairperson is appointed, no appeals can be heard.”

To effectively tackle cyberthreats, say experts, India needs to have a firm hold over electronic data. In fact, data could well be the new oil, according to Raghu Raman, founding CEO of National Intelligence Grid (NATGRID) and group president (risk, security and new ventures) of Reliance Industries Ltd. “Be it a chip in a cellphone or the hardware of a computer or laptop, we have no idea what is placed inside it. We do not manufacture it, and we don’t know what goes on inside it. We have no knowledge of the innards of the operating systems of Apple and others,” he said. “The point I am making is, the smartphone you are holding, the operating system powering it, the hundreds of applications running on it… pretty much all of it is in foreign hands. The irony is, a country that prides itself on its IT prowess has virtually nothing it can call as its own intellectual property.”

According to Prof Sandeep Shukla, head of the cyber cell at IIT Kanpur, India should strive to develop its own hardware and software. Today, the country does not have the technology for manufacturing chips. The government had started a semiconductor complex in Chandigarh in 1978, but it did not take off. But, according to Shukla, it is never too late to focus on such an endeavour.

DGP Chander said India had not witnessed a major cyberattack, as its systems were still not wholly operating in the cyberspace, nor were they heavily dependent on it. “Till 9/11 happened, no one thought it was possible to carry out such an attack,” he said. “Let us not wait for a major cyberattack to wake us up.”