Khaled survived hell. Only he does not seem to realise it. When asked if he has nightmares at night, the teenager laughs, revealing his white teeth. Scared? No, he was not scared. Not even when he was shot through the neck. “It was war,” he said. “We were used to it.”

After several months in one of the most violent organisations of the Middle East, Khaled still has his childhood naivety. Slender, with a peach fuzz moustache and long, dark and dishevelled hair, he looks around the cafe curiously while slurping red berry cocktail through a straw. At the other end of the room, a musician hums in Turkish and plucks at the strings of his oud. Khaled had picked an isolated table to sit at. A refugee in Sanliurfa, southeastern Turkey, he is discreet.

Legend has it that this holy city near the Syrian border was the birthplace of Abraham, the Hebrew patriarch. Now it is a stopover for foreigners volunteering with Islamic State. Khaled joined IS at 13 and escaped last December. For IS leaders, he is a deserter.

Khaled "enlisted" in September 2014. He was living with his family in Al-Tayana, a hamlet perched above a bend of the Euphrates, just on the edge of Syria. One morning, Khaled and a 14-year-old cousin crossed the river and headed to Mayadeen, the closest town. Their families were completely unaware that the boys were headed to the local IS office.

Outside the IS office, the cousin panicked and fled. Khaled went in and offered his services to the wali, the representative of the “caliphate”. Like many "senior members" of IS, Abu Khair al-Iraqi, too, was from Iraq. “I wanted to go with them,” Khaled said. Why? "I felt attracted to them," he said. “I liked their appearance and I wanted to fight Bashar al-Assad's army.”

And, what else could he do? In July 2013, the men in black had conquered the province and shut down all schools. They talked about starting new school programmes, but banned most subjects: chemistry, physics, sport, political science, maths and philosophy. They also banned almost all TV channels. The only channels available were ones such as Quran TV, Al-Resalah TV and Iqraa TV.

In town, the Hisbah, the "religious police," go through cellphones to check content, hunt down smokers (caning and four weeks in prison) and stop women who break the dress code. "If a woman wears a skirt they consider too close-fitting, the Hisbah force them to buy a looser abaya from their own shop," said Omar Mohamed, a temporary teacher who hails from a village near Al-Tayana. The people implementing sharia law are often foreigners. "The worst are the Tunisians," Mohamed said. "They hit those who don't obey, even the elderly.”

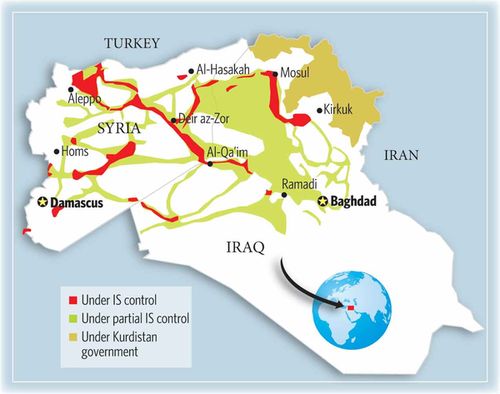

Source: BBC

Source: BBC

Khaled's father, who was a carpenter, died years ago. Most of his brothers left to work on construction sites in Saudi Arabia. Left to his own devices, Khaled did not go further than grade school, and, for the past three years, has only known gunpowder. Bombings by the regime, rebel groups fighting each other over oil fields around Deir ez-Zor, and, more recently, US airstrikes on oil wells and refineries held by IS.

IS offered him 7,000 Syrian pounds per month ($30), far less than the $400 foreign fighters earn, but still a substantial sum in a country devastated by war. Khaled took the offer and left home, without even telling his mother.

IS sent him further north, to a former military base in Tibni. The International Atomic Energy Agency had investigated the base a few years ago on suspicions that it was being used to store nuclear waste.

The teenager found himself in the middle of the desert with 300 other recruits, almost half of them foreigners. Approximately 30 were as old as Khaled. IS issued them loose, sand-coloured kurtas and pants cut at the calves.

The daily routine began at 4am, with the dawn prayer. Afterwards, the recruits jogged, did obstacle courses and practised martial arts until 10am. The 'drill sergeant' was a Frenchman called Abu Moussab al-Faransi. "A tall guy, like a muscleman," said Khaled.

After a break, the group attended two hours of sharia law classes given by an imam, a Tunisian. "Classes were held in a warehouse,” Khaled recalled. "He told us we had to kill all apostates. It was our duty.”

After the lunchtime prayer, an Iraqi commander taught them to shoot a Kalashnikov and handle explosives. The recruits then sat through another sharia law class, followed by guard duty and evening prayer. Lights were turned out at 9pm.

Another 17-year-old recruit recently told The Wall Street Journal that he and other boys, some as young as eight, were taught to behead people. "It was like learning to cut onions," he told the journalist.

Khaled said that in his case the training was very concise and that he did not witness or take part in any executions. He said he did not have time.

After 15 days, Khaled's superiors sent him and others to the frontline near Triff, a hamlet to the southeast of Raqqa. It was a bloodbath. Lacking combat experience, most of the recruits were killed in the first engagement. On the second day, Khaled was shot in the neck, but survived.

Khaled said he is not scared of death, but is not "seeking martyrdom" either. He was simply playing war. "We did not even know whom we were fighting. They told us it was a group of armed thieves,” he said.

He later discovered that he was fighting the Ahrar ash-Sham (Free Men of the Levant), a rebel Islamist faction with close links to Jabhat al-Nusra (Victory Front), which is itself affiliated to Al Qaeda.

"When I learned who our enemies were I was in a state of shock," said Khaled. "I asked lots of questions. They told me they were bad Muslims, they quoted the Prophet, various Hadiths and verses from the Quran."

When he left hospital, he was not sent back to the frontline, because of his wounds. They assigned him to man one of the many roadblocks that are spread across the desolate territory. The new assignment meant long watch hours in the middle of nowhere, inspections, searches, interrogations and asking trick questions on Islam to catch non-Muslims.

The teenager who dreamt of fighting Bashar al-Assad’s regime had turned into a police officer. The enthusiasm of the early days slowly waned.

Meanwhile, Khaled's mother had set out to look for him. From the cousin who had gone with him to Mayadeen, she learned about his enrolment in IS. She begged IS leaders to return her son. “Impossible!” she was told. "We need fighters."

But, they did allow her to see Khaled. The meeting took place at the gates of the Tibni base, in a house occupied by a general, Abu Hamza al-Askari. She implored him to let her son go. Abu Hamza, who would be killed a few weeks later in the Kurdish city of Bane, also refused.

The mother refused to give up. She returned a fortnight later, this time accompanied by one of her other sons, a mechanic, and again asked that Khaled be released. This time her efforts paid off. "After a two-hour discussion, Abu Hamza agreed to grant me leave,” said Khaled. "I left my weapon and uniform, and went back home. I was happy. After three months of absence, I missed my family, but I still thought I would go back to fight.”

Back home, he learned from his brother and uncle that several members of his family had been killed by IS while fighting in the ranks of other rebel groups, including the Free Syrian Army. "They spent several days trying to convince me," he said. "In the end, I got angry and left IS.”

In Syria, though, the front lines keep moving, as do alliances. Jabhat al-Nusra launched an attack against his village and took him prisoner. "They kept me in the headquarters. They did not beat or torture me. They only questioned me on the Tibni base,” he said. They released him after 12 days.

Al-Tayana was soon recaptured by IS and he stood the risk of being arrested and executed for desertion. He had no choice but to run. His parents got him fake identification papers to get past checkpoints. To hoodwink IS, he travelled with a woman from the village and her children. "I said I was part of their family," he said.

After a long journey, he arrived in Turkey. He now hopes to join his brothers in Saudi Arabia. Looking back, does he think it is normal to send a 13-year-old to the frontline? “No, it is dangerous," he said. "But, IS does not care. And, we are easy to convince."